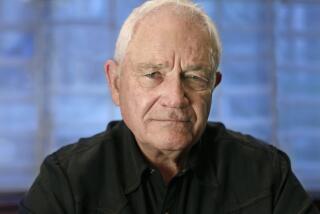

David Mackenzie on avoiding ‘Game of Thrones’-style fantasy — and ‘Braveheart’ comparisons — with his medieval epic ‘Outlaw King’

Throughout his film career, director David Mackenzie has bounced unpredictably among genres and styles, from the somber 2003 drama “Young Adam” to the 2009 sex comedy “Spread” to the 2011 sci-fi film “Perfect Sense.”

“The idea of repeating old ground feels unattractive to me,” he says. “Each film has to feel like it’s a new journey.”

Now, on the heels of his biggest success — the 2016 crime thriller “Hell or High Water,” which earned a best picture Oscar nomination — Mackenzie, 52, has taken a journey seven centuries into the past, retelling one of the most important stories in his native Scotland’s history with his latest movie, “Outlaw King.”

Opening today in select theaters and also streaming on Netflix, “Outlaw King” chronicles the rise of Robert the Bruce (Chris Pine), the Scottish ruler who waged a guerrilla war in the 14th century against a far larger English army. Epic in scope and punctuated by muddy, bloody battles, the film has drawn inevitable comparisons to Mel Gibson’s 1995 hit “Braveheart,” which told a different version of the story of the Scottish Wars of Independence and won the best picture Oscar despite criticisms over its historical inaccuracies.

Mackenzie spoke with The Times about bringing a sense of gritty realism to medieval Scotland, his issues with “Braveheart” and why he was happy to make a big-scale epic for Netflix.

What was the initial germ of this movie?

This was a project I’ve had floating around for a few years. I’d been waiting to do something in the medieval world that was a little bit more detailed and less mythological, to try to remove some of the tropes of medieval life and relate some of the physicality of what that world must have been like — and this great Scottish story had been in the ether for a while.

I don’t really like to say it, but everyone in Scotland feels that “Braveheart” somehow or other misinterpreted the story and that Robert the Bruce was given short shrift in that version. That sense of needing to right the wrongs of that film was somewhere in the back of my mind as well. I don’t really want to stand in opposition to that film — the two films exist 20 years apart, with different sentimentalities, different methods of filmmaking, all sorts of differences. Initially, I tried not to even think of it, but I realize now it’s kind of the elephant in the room.

Aside from “Braveheart,” for today’s audiences, a lot of their sense of this kind of world comes, in a more fantastical way, from “Game of Thrones.”

That was one of the challenges of the film: to stop that fantasy element and all those tropes from creeping in. I was always calling our film an “anti-fantasy film.” With the production design, the costumes and all of that, I said: “Let’s not use our imaginations here. Let’s look at what we can of the evidence of what life was like.” We were looking at tapestries and drawings and even things that came out of [peat] bogs. We were never going for that maximalist, fantastical extravaganza kind of thing. We wanted to demythologize these things and try to get under the skin of them.

Robert the Bruce is a hugely important figure in Scottish history, but Chris Pine is not Scottish. Were you concerned going into the film that there would be an extra level of scrutiny and maybe skepticism from people in Scotland about his performance?

In the course of the long genesis of the movie, there were all sorts of people we thought about, but when it came close to the film becoming a reality, it was very easy to settle on Chris. He’s got a great physical presence and great sensitivity, and he’s able to delve underneath the surface of nuanced characters.

The first minister of Scotland [Nicola Sturgeon] saw the film the other day, and she tweeted what a great movie she thought it was and how wonderful Chris’ accent was. A lot of people in Scotland are saying that, as far as they’re concerned, his accent is the best non-Scottish version of a Scottish accent they’ve ever come across. It’s a hard accent to do. It doesn’t come easy to a lot of people. But Chris did a really great job.

The battle sequences in this film have a real sense of chaos and savagery. How did you approach orchestrating that kind of mayhem?

We were trying to go for that sense of brutality, of violence that is short and messy and not very nice. It’s not sexy and smooth and balletic. It’s definitely not my interest to glorify violence, and I felt it was extremely necessary to show a real sense of what the sort of blunt force of medieval warfare must have been like.

We choreographed the action but not in a way that it was aestheticized — it was more to make it very raw and immediate. We were helped by the fact that the environment we were in became very muddy and had that kind of slippery quality. That makes it harder to do, because you have to be careful of people’s safety, but it does give a sense of the muck and blood and general chaos of it.

You went back and significantly re-edited the film after it premiered at the Toronto Film Festival in September. Why?

Well, I rushed the film for Toronto because we wanted to put it out on a big platform. I would have loved to have called it a work-in-progress, but I thought that would be a rude thing to say. But when I saw the film there, I wasn’t happy with it, so I wanted to go back and do my best to fix it.

It was really a case of going back in and scratching a few of my own itches. We only had about a week and a half to do it, and I ended up cutting about 22 minutes. I think the film plays a lot better and I’m happy with it now.

This is an epic film that is clearly intended to be seen on a big screen and not on an iPad. In your early conversations with Netflix, did they give you the confidence that they’d give it a serious theatrical push?

Yeah, that was very much what they said. I’ve really enjoyed the experience of working with them. They’re very filmmaker-friendly, and it just feels like a very exciting place to be now. I don’t know how many studios would be making a film on this level of ambition that wasn’t a kind of superhero movie or that sort of thing. It’s a film that was made for a sense of big scale and obviously, I’m delighted for anyone to watch it on as big a scale as they can.

My ideal scenario is to imagine Netflix having their own theater chain and putting out movies that, if you want to watch them on the big screen, you can, and if you want to watch them at home, you can do that too. It seems like that’s a logical thing. There’s no real reason why that shouldn’t happen.

This movie clearly shows you can work on a huge canvas with a big budget. Would the idea of taking on something like a comic-book movie or another type of giant studio franchise film appeal to you?

I’d prefer to be the person starting the franchise rather than the person following in the footsteps of the franchise. I’m not sure how much I could get into the idea of having to embrace so many things that are already set up.

Obviously, it depends on the project and what it is. But I’m definitely into the idea of making big-scale films. I really enjoyed the wider parameters of this film and the opportunities it gave me as a filmmaker. That’s something I’d love to have another chance at.

REVIEW: Chris Pine stars in the ripsnorting Netflix epic ‘Outlaw King’ »

Twitter: @joshrottenberg

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.