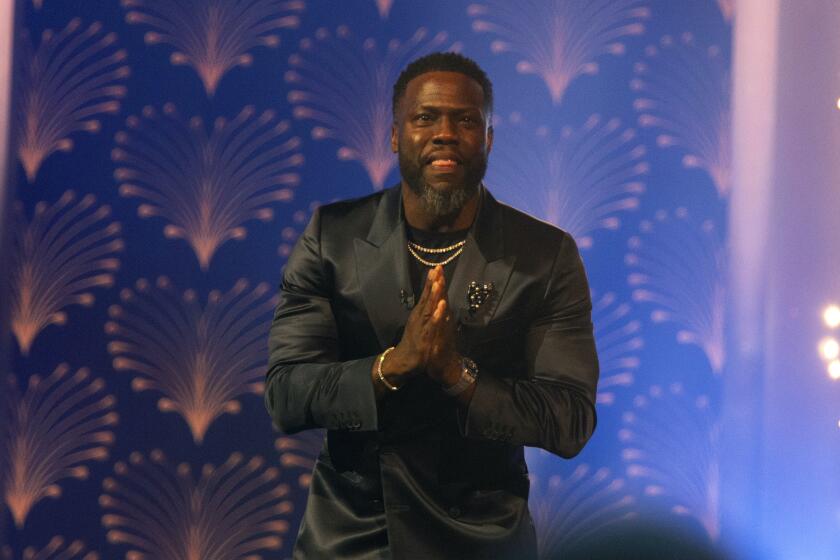

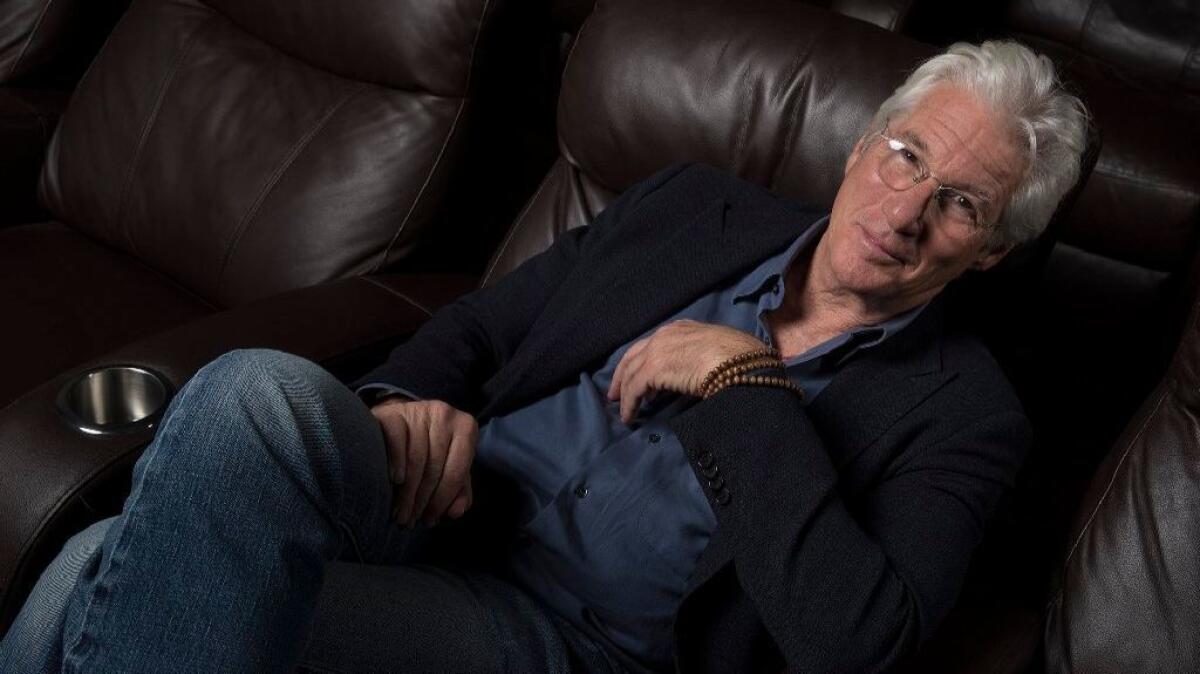

Richard Gere as a schlubby Jewish ‘fixer’? Absolutely, if given enough time to get into his skin

In Richard Gere’s latest film, “Norman: The Moderate Rise and Tragic Fall of a New York Fixer,” released earlier this year, Israeli writer and director Joseph Cedar lends Gere perhaps his most profound role yet: Norman Oppenheimer, a New York Jewish businessman who connects parties together for profit. The veteran actor inhabits the role with much vulnerable nuance and potent skill.

“It’s an entertaining but a difficult movie,” Gere says by phone from his Beverly Hills hotel before flying out to Moscow later that evening. “[Norman’s] not Madoff. The guy is not a thief, he’s not hurting anyone. He’s honest in that he really does want to deliver these things he promises people. And that’s why in the end he finds a way to give everyone what he originally promised them. He ultimately gets what he wanted; he will eternally belong. He’s the hero of the story. He just wanted to be at the table.”

You had about nine months to prepare for this role, which I assume is a true luxury for an actor?

Obviously, the character Norman is pretty far away from me. Joseph is meticulous, and wrote an incredibly beautiful screenplay. He had a lot of poetic stuff — much of which found its way into the Norman that started to emerge. We were doing rewrites throughout that whole period. I’m asking questions, a lot of which he hadn’t thought about.

I understand before you took the role you asked him, “Why me?”

Yes. We’re friends, and he gave me the script, and I called him and said, “Joseph, this is a beautiful script, but I’ve got to be honest with you, why me?” If I was directing and producing this movie, I don’t think I’d go to me. There are certainly a lot of other actors you would think of first, for this rather schlubby New York Jewish character.

What did he say?

“Look, I know. But I don’t want them. I want to see what you’d bring to the table. I want to find something that isn’t obvious, and not the first thought.” So we started working very slowly at how to arrive at Norman. And it was incredibly surprising, how he emerged, this guy to the point where I felt completely comfortable with him, getting in and out of him.

Where did all the physical stuff come from? That bouncing sort of walk versus a strident stride …

It’s funny, after I saw the film I could see where a lot of this came from. I wasn’t thinking about this at all, but when I looked again at the film, I’m seeing a lot of Charlie Chaplin in there. These kinds of holy fools who are a little jittery and displaced, homeless.

Kenneth Turan reviews “Norman: The Moderate Rise and Tragic Fall of a New York Fixer,” directed by Joseph Cedar and starring Richard Gere, Lior Ashkenazi, Michael Sheen, Charlotte Gainsbourg, Steve Buscemi and Dan Stevens. Video by Jason H. Neubert.

And that’s the other thing, is Norman homeless? The audience sees him without a home the entire story.

He’s like a turtle, he carries his home with him, you know? He’s got that coat, and all his items, his phone and earphones. I do think he’s kind of a holy fool, I do. I don’t know if he’s conscious of it but he does function in the world like that. Like the Tramp. And when I said that to Joseph about the holy fool, he said, “Yes, but he still wants his 7%.”

One odd but intriguing thing about Norman is that no matter how much he’s dumped on and humiliated, he never seems to get angry.

I kept asking these questions about him in the beginning. “What does he do with all this humiliation? Does it build ’till he has to explode?” Joseph didn’t have an answer for that. What he did say was — and this was from a deep Jewish experience: You can’t afford to express anger; you’ll be the first one jettisoned, so you don’t show that emotion. You evolve other emotions; empathy, understanding, more sympathetic things. You keep your eye on the prize.

We actually have a scene — where he has his own name card at the big table, and that was an enormous thing for Norman. It’s not that he doesn’t feel the humiliation, he is just so quickly able to transform it. And that’s unusual in all the characters I’ve played.

What about that ending?

He’s conscious of the world he’s in [the betrayal] at that point. How we played those scenes is not someone avoiding the pain, the pain is washing over him. And he still makes that decision to make his life meaningful by making everyone achieve their wishes. He’s very calm at the end, for sure. He feels like he’s done it finally.

WATCH: Video Q&A’s from this season’s hottest contenders »

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.