Appreciation: Getting to know Marty Sklar, a man who shaped Disney theme parks

One doesn’t join Imagineering to become famous. Such was a phrase oft repeated by Marty Sklar, a longtime leader of the Walt Disney Co.’s highly secretive division dedicated to creating new theme park experiences.

Sklar, also once a speechwriter for Walt Disney himself, regularly had to tell young, ambitious designers that only one name would ever appear in lights: Walt’s.

So it wasn’t always easy to get Sklar to take credit for his accomplishments in his five-plus decades with Disney.

I certainly tried.

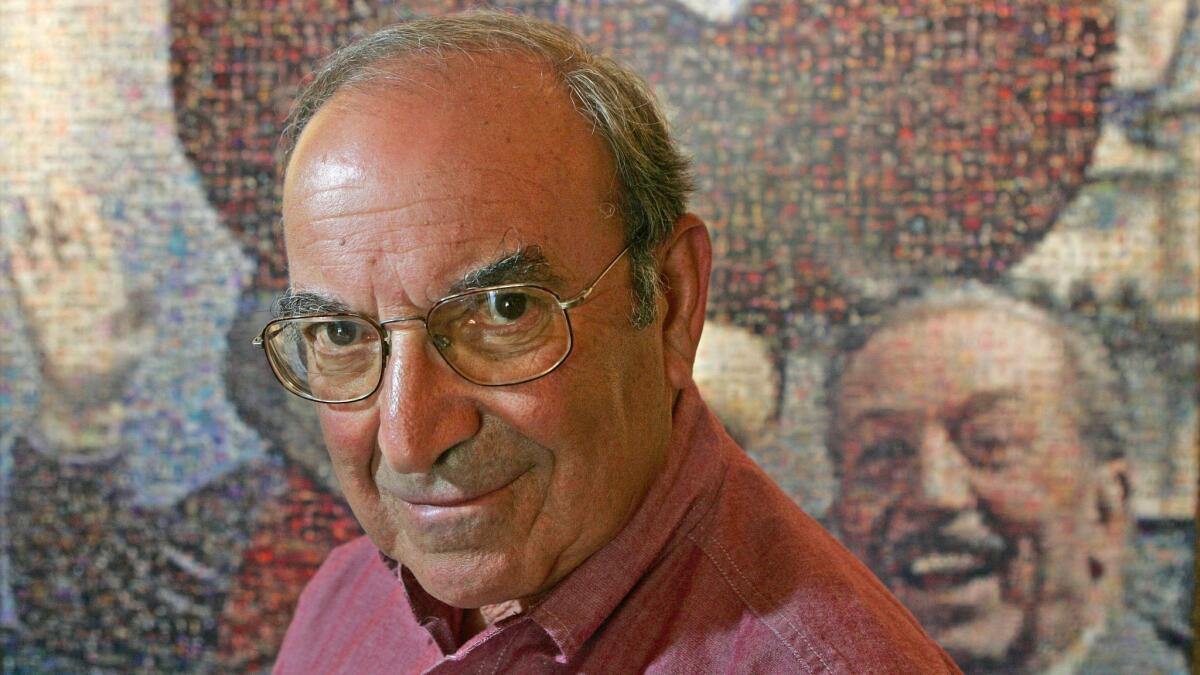

Over the last three years, I had gotten to know Sklar, who died Thursday in his Hollywood Hills home at age 83. Just seven days prior, Sklar and I spent several hours at Echo Park’s Taix French Restaurant — his pick — to chat over a meal.

I always had a lot I wanted to discuss when we spoke. Sklar, after a short stint at Disneyland, joined Imagineering in 1961, staying through 2009. If you visited a Disney park during this period, chances are Sklar had some hand in something you enjoyed.

These decades saw tremendous advancements in themed entertainment, from the all-enveloping tome to adventure that is Pirates of the Caribbean to Walt Disney World’s optimistic look to the future and wide embrace of international culture that is Epcot. Sklar did a little writing on the former and helped shape the latter, ensuring that Walt’s vision for a utopian city would live on in theme park form.

As a Disney parks devotee, I cherished these conversations, long believing that the resorts, though beloved as tourist destinations, don’t get their due as theatrical, cultural and technological institutions.

Sklar was always happy to oblige. He’d share tales of aborted attractions — the thrill ride that would take guests through the innards of a computer, once pitched to sit where Walt Disney World’s Space Mountain rises today (sponsor RCA didn’t go for it) — and even divulge the occasional frustration (he too was a bit disappointed in the first pass at Anaheim’s Disney California Adventure).

But over time, our emails, phone calls and in-person chats became less about me pestering him for little-known tidbits. On July 20, for instance, Sklar probably asked me more questions than I asked him.

Some were Disney related. What first inspired my love of the Disney parks? That was easy: the Walt Disney World monorail, an answer that led to a spirited round of tales about unbuilt monorail lines and the difficulty in trekking the tracks from Seattle, where he said they were constructed, to Orlando, Fla.

But many questions were about journalism and my own career. He offered management advice and took a keen interest in the process of putting together a reported article. Before joining Disney to create a newspaper for Main Street, U.S.A., Sklar had dreamed of being a sports journalist.

Indeed, at one point, I asked Sklar to simply tell me one of his greatest career accomplishments. It’s a silly question, I know, especially for someone I’ve spoken with numerous times over the years. But by this point, I had grown accustomed to Sklar listing the names of a dozen other Imagineers he thought were more important than him whenever I mentioned a project.

Once, when conversing about the Haunted Mansion, I brought up the text he wrote for a sign that was placed outside the attraction in 1965, four years before it would open.

“Post-retirement leases are now available in this Haunted Mansion,” it read, and the marker went on to pitch the attraction as a sort of retirement home for ghosts — “a country club atmosphere” for “ghosts afraid to live by themselves.” I liked that tinge of loneliness Sklar brought to what was otherwise a playful placeholder.

Sklar dismissed any sense of creativity on his part, noting that the passage was inspired by a quote from Walt after he a told a reporter in Britain that he was overseas to gather “ghosts who don’t want to retire.” Sklar further downplayed his work, claiming the only reason anyone bothered to read the sign was because his fellow Imagineers gave it a lovely design with a flying skull bat.

But over the years, I kept pressing. I simply wanted to know one creation that made him proud.

His answer? It was as a student at UCLA in the mid-1950s. Then, he said, he got to travel with the Bruins basketball team for the college paper. He was pleased, he said, to get to document the work of legendary coach John Wooden.

While I may have been hoping for a yarn about, say, the creation of Epcot’s glistening sci-fi orb Spaceship Earth, I don’t believe Sklar picked a non-Disney achievement because he was coy about sharing details about his time with the company.

Far from it, as we routinely discussed the challenges he faced in maintaining Imagineer morale, especially, as he regularly noted, one could work five years or more on a project, only to see it be set aside.

He once told me of a tense pitch meeting with then-Disney Chairman Michael Eisner for a proposed water park in Walt Disney World.

“We had three really good ideas,” Sklar said. “I set up a conference room for Michael Eisner to come in and look at the three ideas. I was going to have each of the teams take him through one at a time. He walked in and said, ‘That one,’ and then left. It was obvious that was the best one, but I had two teams that didn’t even get to present.”

Although I can’t speak of Sklar with the insight of his former coworkers or those he mentored, I did witness how he saw his role as less of a designer or a business leader and more of a custodian of that which belonged to others. He often spoke of Imagineering as something akin to an apprenticeship rather than a career, noting his own unconventional rise and explaining the job as a set of ideals as much as a set of skills.

He also possessed an unwavering belief that theme park design is an art form worth investing in. He noted the reason audiences didn’t take to the original version of California Adventure was because it moved away from large-scale world creation and instead focused on less immersive rides, the latter word one he always used with a hint of derision.

And yet Sklar didn’t live in a fantasy universe. He once gave me a rather enlightening piece of wisdom, one that, yes, could apply to Disney theme parks, but also to a career or a love life. “One of the most important things,” he said, “is you can’t have precious ideas, because so many times it’s not the right time.”

To not dwell on what’s out of our control is easier said than done, but it’s a lesson in optimism, and Sklar certainly possessed it.

Anyone who ever communicated with him is likely aware of the three words that ended many a correspondence, and a phrase I’ll remember when thinking back on the joy of getting to know someone responsible for so much that’s close to my heart: “All good things.”

ALSO

This is your brain on Disneyland: A Disney addict’s quest to discover why he loves the parks so much

Meet Disney’s philosopher king: the brain behind ‘Avatar’s’ Pandora and Marvel’s ‘Guardians’ ride

Digging up the ghosts of Disneyland’s Haunted Mansion ride

Going solo at Disneyland helps the imagination go wild

Behold animatronic Cosmo (and Rocket) inside Disneyland’s ‘Guardians of the Galaxy’ ride

Follow me on Twitter: @toddmartens

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.