Café Tacuba remakes itself yet again

It started out as an inside gag, a bit of dadaist prankster wordplay.

When Café Tacuba began thinking about a title for its new album, the Mexican alt-rock band opted to pay tongue-in-cheek tribute to the shape-shifting Artist Formerly Known as Prince. Thus was born “El Objeto Antes Llamado Disco,” which in English translates as “The Object Previously Called a Record,” the band’s first studio release in five years.

“It was a joke,” says José Rangel, a.k.a. Joselo, the band’s lead guitarist and sometime vocalist, speaking by phone in Spanish. “But we also felt that it speaks about this situation that we are living, we as musicians that have an interest in bringing our music to the people.”

MUSIC REVIEWS: The latest album and live reviews

Indeed, as the new disc took form in recent months, its mysterious title acquired unforeseen shadings. The ambiguous name resonated with other unconventional artistic choices that Café Tacuba made, including the quartet’s decision to make the new record in front of live (but silent) studio audiences in Los Angeles, Buenos Aires, Mexico City and Santiago, Chile.

As the band members pondered the title, they also realized it could refer to the topsy-turvy state of the music industry, as downloads and the Internet cannibalize the CD market while true hi-fi connoisseurs have transformed themselves into vinyl fetishists.

Even the new record’s songs — a colorful tangle of pensive ballads, spiky electro-pop and guitar-driven ‘60s-retro Peruvian psychedelia — suggest a break with the past, a desire by the band to wipe the slate clean of prior assumptions.

PHOTOS: Celebrities by the Times

Obviously, Rangel says, the band’s music, like the music business itself, has changed drastically since Café Tacuba’s first record came out two decades ago. But one thing, he insists, has not.

“Music goes on,” he says. “It’s not important if there are changes in formats, and in MTV3, and in the Internet, and in records, or in tapes, or in anything whatever. There are old blues musicians or old Mexican songwriters, traditional musicians, and the formats change, the industry changes, and it doesn’t make any difference to them. They keep making their music. And I believe this is the best way to continue.”

Pressing forward by upending their own precedents has been a rare constant with Café Tacuba, probably the most consistently unpredictable “rock en español” group of the last 20 years.

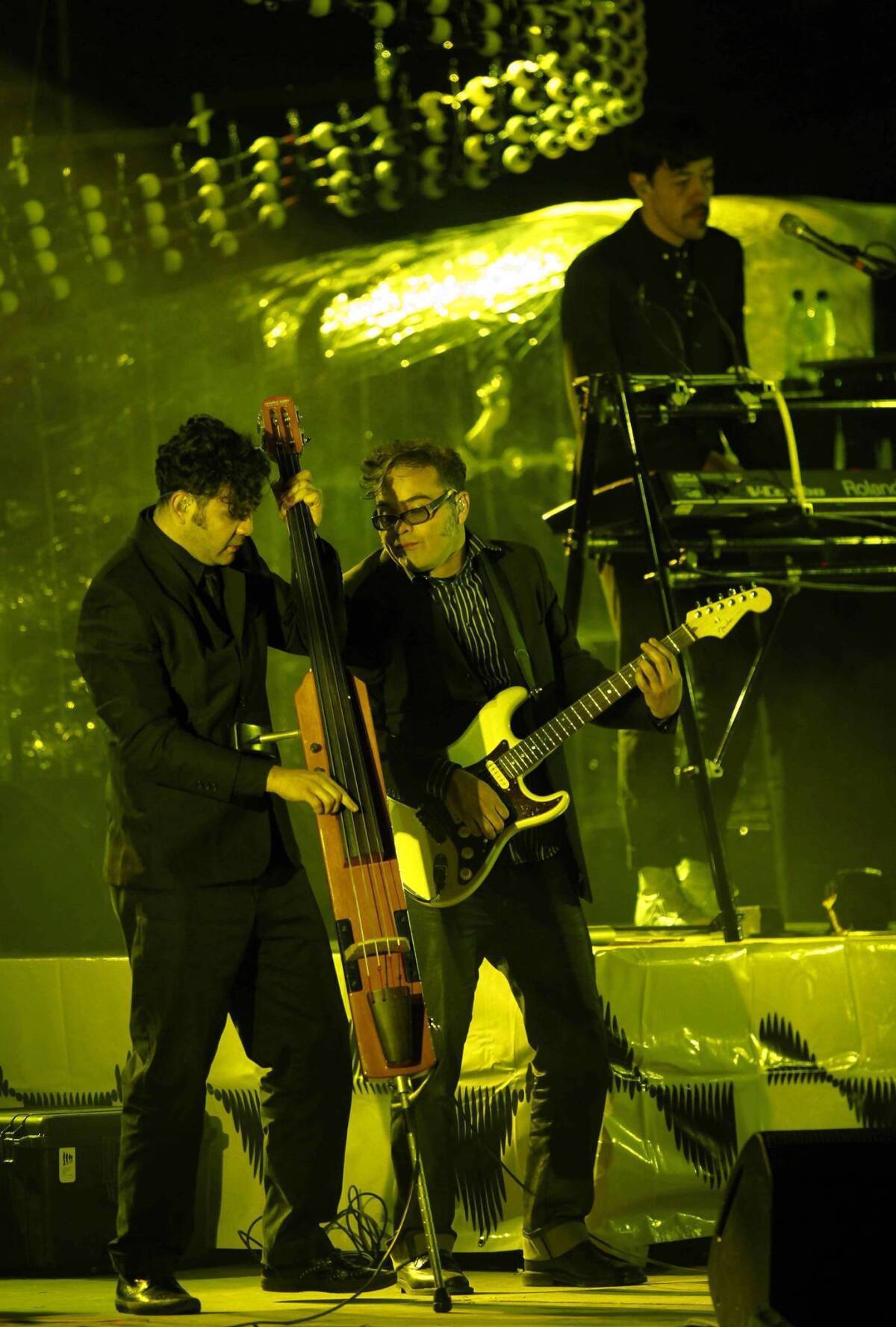

Like Prince, the band — whose other members are Rubén Albarrán, lead singer and rhythm guitarist; Emmanuel “Meme” del Real on keyboards and piano; and Joselo’s brother, the bassist and ukulele player Enrique “Quique” Rangel — has a chameleonic capacity to shift moods and musical genres seemingly at will.

The band’s self-titled 1992 debut album stitched together traditional Mexican instrumentation and faux-naif vocals with ska-punk guitars, a deluge of Mexico City references and an overall fury befitting the Sex Pistols (one song, “P--- Juan,” was a Johnny Rotten homage). The band’s “Cuatro Caminos” (Four Paths), which won the 2003 Grammy Award for Latin rock/alternative album, fronted a techo-funk persona. Its 2007 “Sino” slid sideways into Motown and classic British Invasion rock.

The personification of that mercurial spirit is the diminutive Albarrán, a hopped-up stage presence who goes by a slew of aliases, among them Anónimo (Anonymous) and the ersatz-Aztec Ixxi Xoo, and might turn up at any given show dressed as a cowgirl or in a chicken suit. But all the band’s personnel practice perpetual musical reinvention.

“I think they let everything in, and then they sort it out inside and keep whatever they think is going to be useful to them,” says Gustavo Santaolalla, the Argentina-born, L.A.-based musician and composer of film scores including “Brokeback Mountain,” who discovered the band playing at a Mexico City cafe and has produced all of its studio albums to date. “They’re thoroughly open to all kinds of music.”

In preparing to make “El Objeto,” the band followed its usual working method: dropping out and turning inward.

“The moment when we start thinking about a new disc, it’s very strange what follows after that,” José Rangel says. “It’s a very special moment in which the world disappears, and also our history disappears, our fans disappear, the critics disappear.”

This time around, that process was aided and abetted by the distance that the band members have placed between their working and personal lives over the last few years. After inhabiting Mexico City’s trendy Condesa neighborhood for some time, Rangel, his wife and their two young daughters fled the capital’s foul air and crushing traffic and decamped for the mystical, New Age-y mountain village of Tepoztlán, an hour to the south. Albarrán also lived there for a spell.

“Each one has built their own life, with their families; they have even moved to different places,” Santaolalla says. “Really in these last few years they’ve seen each other very scarcely, and they didn’t talk that much to each other” — not due to any fissure within the band, he adds, but because they were busy leading their lives, not being rock stars.

“They have grown as people and as artists,” Santaolalla says.

Rangel says that when the band started working together on the new album in Tepoztlán, it was Albarrán who came up with the idea of recording the disc before a live audience, only minus the ecstatic clapping and rebel yells that are de rigueur in most live records.

“Because of the different locations, there were different interpretations of the songs,” Santaolalla says. “We ended up using the bass, perhaps, from Chile with the vocal from Mexico with a guitar from the demo. We used everything that we had to finalize the album.”

Searching for a distinctive sound befitting the new record, Rangel ditched his acoustic guitar for a Gibson ES-335, an electrified, semi-acoustic model favored by the Foo Fighters’ Dave Grohl. The payoff shimmers through hard-edged tracks like “Olita de Altamar,” with its psychedelic-spaghetti western riffs. At another end of the album’s sonic spectrum are the spiraling, mirage-like keyboard swirls of “Zopilotes” (Buzzards) and the thumping, meditative “De Este Lado Del Camino” (From This Side of the Road).

The latter, says Rangel, may be as close to a philosophical summing-up as Café Tacuba has produced. So far, anyway.

“It’s a reflection about life that, yes, we also can apply to the group. This road that we’re following, we’re not searching for any place to arrive at. It’s about the journey; the destination is the journey. So we’re going to live it with every record.”

PHOTOS AND MORE:

PHOTOS: Iconic rock guitars and their owners

The Envelope: Awards Insider

PHOTOS: Unfortunately timed pop meltdowns

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.