Kraftwerk’s ‘Trans Europe Express’ started the musical revolution

Kraftwerk’s “Trans Europe Express” is the most important pop album of the last 40 years, though it may not be obvious.

The first high-art electronic pop record, “Trans Europe Express” set the tone for the coming revolution, became one of the central texts of hip-hop, pop and electronic dance music. Recorded in the same few months of mid-1976 when Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak incorporated Apple Computers in Cupertino, “Trans Europe Express” and its predecessors, “Radio-Activity” and “Autobahn,” sparked a similarly massive upheaval with sound.

That it was built by a couple of Germans searching for new ideas in a postwar land longing for a modern reboot makes it even more astonishing and its span of influence more notable.

PHOTOS: Unexpected musical collaborations

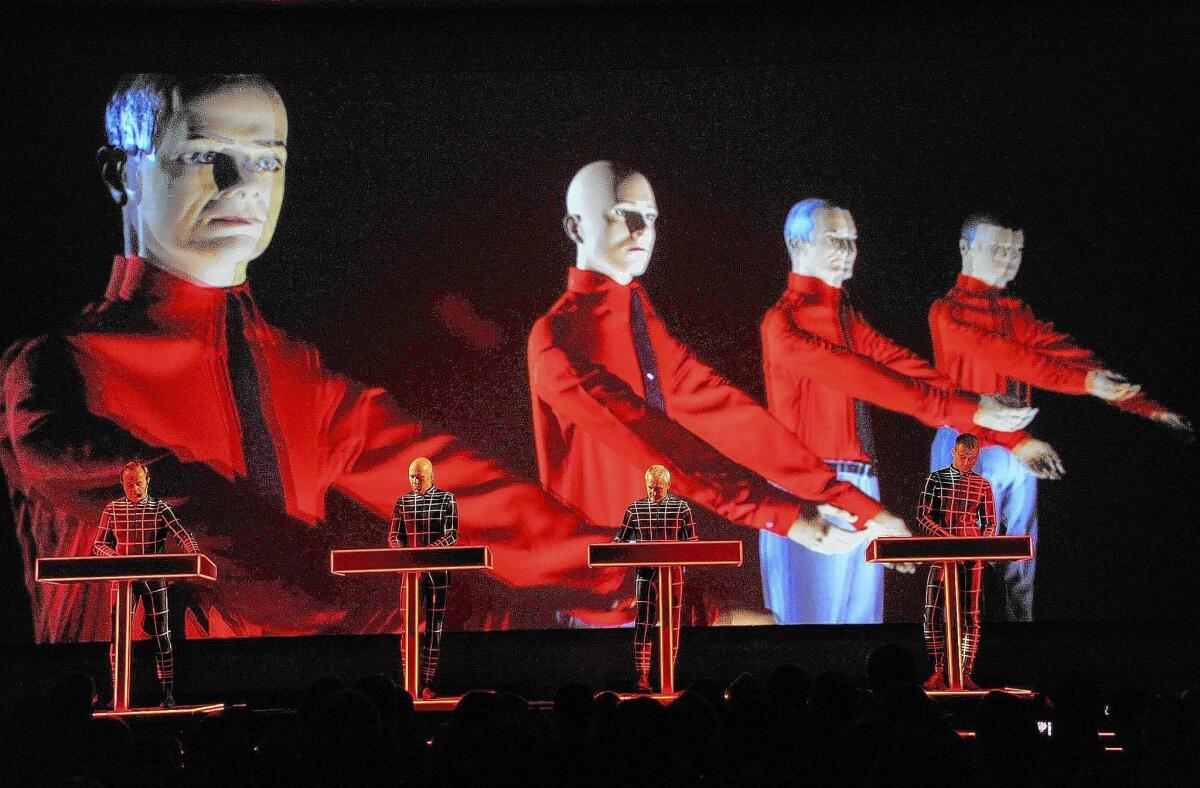

On March 18 the group arrives at Walt Disney Concert Hall for four nights of eight sold-out performances to play in their entirety the eight albums that helped define the electronic music era. The shows open the Los Angeles Philharmonic’s “Minimalist Jukebox” festival and are similar in execution to residencies at London’s Tate Modern and Museum of Modern Art in New York last year. It will be the group’s first performance in Los Angeles since 2005, and, according to gig site setlist.com, only the third time it has played here.

Founded by Ralf Hütter and Florian Schneider, Kraftwerk’s work from the 1970s and ‘80s helped bring computer-based synthetic pop music into the mainstream while imagining a borderless sound stripped of dialect and regional tone in favor of the precisely immovable rhythms of the machine.

The sound is now apparent throughout culture: synthetic bleeps, dotted out in melody while Plasticine rhythms locked into a groove through mathematics rather than human intuition. It’s in the relentless thump of a million EDM tracks, weaves through the work of Jay Z, Timbaland and Pharrell. The ways in which they vanished beneath their robotic personas no doubt influenced Daft Punk’s android aesthetic.

Forty years after their official debut, “Autobahn,” dented the U.S. pop charts with an odd ditty about the joys of driving Germany’s main superhighway, the robotic quartet are still working to secure their legacy. Or at least Hütter and three other emotionless men standing onstage like mannequins are. Schneider retired in 2008, shortly after a creative burst that saw them rework old material, release new music and attempt to rejoin a musical discourse that had blossomed in ways that seemed unimaginable a few decades earlier. (The band has mostly disavowed its earliest three albums, from 1970 to 1973, much of it created on non-electronic instruments.)

PHOTOS: Hard Day of the Dead Festival 2013

The missing members don’t matter much, considering the group intentionally erased any hint of human personality from its performances. In dehumanizing themselves, the members also removed the main thing a skeptical, rock-focused music media required of their geniuses in the ‘70s: oversized personality and a guitar. Rock arbiter Rolling Stone magazine ignored Kraftwerk when it wasn’t outright hostile toward the group or any other act deemed suspect for use of electronics.

“Valuable as both a musical oddity and background music for watching tropical fish sleep,” wrote one reviewer of the group’s output in “The Rolling Stone Record Guide” of 1979.

“I once convinced myself to enjoy this band — if there had to be synthesizer rock, I thought, better it should be candidly dinky,” wrote Robert Christgau, the self-described “dean of American rock critics.” He was writing about “Computer World,” Kraftwerk’s prescient 1981 love letter to home computers, pocket calculators and a digital future.

The American confusion makes sense.

The sound was built in Dusseldorf, at a time when a culture recovering from catastrophe was starved for something fresh. Their biggest native inspiration was avant-garde composer Karlheinz Stockhausen, who also influenced the sounds of kindred experimenters in groups including Can and Tangerine Dream. “When we started it was like, shock, silence,” Hütter told writer John Savage in a rare 1991 interview. “Where do we stand? Nothing. Classical music was of the 19th century, but in the 20th century, nothing. We had no father figures, no continuous tradition of entertainment.” (Hütter declined to be interviewed for this article.)

PHOTOS: Musicians’ onstage snafus

Still, if all Kraftwerk had accomplished was to submit that computers and sound synthesizers didn’t have to be cheesy like early 1969 hit “Popcorn” by Gershon Kingsley, pine for highbrow legitimacy a la Wendy Carlos’ “Switched on Bach” or Morton Subotnik’s “Silver Apples of the Moon” or serve a subservient role in a self-serious rock show like one by Emerson, Lake and Palmer, Kraftwerk would be worth a few paragraphs in the pop bible.

But the most influential Kraftwerk pieces were present to help steer rap music. In building music otherwise reliant on a kind of repetition in which players were expected to repeat unvarying 32- and 64-bar mantra-esque loops, Kraftwerk employed early sequencers to automatically perform these simple tasks while humans sang in monotone about “Europe Endless,” or about “Numbers” through thumpy, dry beats and antiseptic melodies.

As it happened, though, the rigid beats worked well with rhyming. One of the music’s most important early DJs, Africa Bambaataa of the Bronx, harnessed “Trans Europe Express” to create his “Planet Rock” in 1982 with his crew the Soulsonic Force.

Hip-hop historian Jeff Chang in his book “Can’t Stop, Won’t Stop,” describes “Planet Rock” as hip-hop’s “universal invitation, a hypnotic vision of one world under a groove, beyond race, poverty sociology and geography,” which is accurate.

“I do think we’re in a new musical age,” Hütter told Savage, adding that it’s been gratifying to see the group’s influence spread. “We have played, and been understood, in Detroit and in Japan, and that’s the most fascinating thing that could happen. Electronic music is a kind of world music.”

Since that first edit more than 30 years ago, hundreds have built tracks using Kraftwerk’s sounds as source material. It’s possible, in fact, to trace the progress of the genre through those who have sampled the Teutonic geniuses, turning their neutral tones harder, adding heavier bass: Afrika Bambaataa, L.A. Dream Team, Jazzy Jay, Kool G Rap, De La Soul, 2 Live Crew, Sir Mix-a-Lot, PM Dawn, Mos Def, Jurassic 5, Jay Z, Madlib, Dr. Dre, Lil Wayne, Lil B.

Ironically, I first truly fell for “Trans Europe Express” while driving through the pastoral beauty of Sonoma and Mendocino counties. Rolling in a midsize rental car with a tape deck, I searched through my backpack to find the only cassette: “Trans Europe Express.” The disconnect of moving through the patchwork hills that line the coast while Hütter sang of “Europe Endless” and humans as “Showroom Dummies” made for this otherworldly moment. The synth washes and melodies hummed while Highway 1 wended, the synthetics taking on a meditative quality.

“The global village is coming, but it may be a couple of generations yet,” Hütter predicted in ‘91, and nearly a quarter century later, the echoes of his and Schneider’s work are readily apparent. It’s in the wisp of vaguely human-sounding synthetics rolling through Katy Perry’s chart-topping hit “Dark Horse,” an echo of the synthesized choir of “Europe Endless,” and in the relentless bump of house music.

In that context, it’s hard not to consider some of Kraftwerk’s most inventive work as opening utterances of the computer age, even if artists began experimenting with computer music decades earlier. “Geiger Counter,” which opens the group’s strange 1975 album, “Radio-Activity,” sounds like the first heartbeats of a newborn calculator. Listening a few generations after its inaugural thump, what’s most striking is how emotionally rich the tone is, how as the track progresses and the beat starts to speed, the energy it exudes is one of excitement tempered with fear, an adrenaline rush similar to the one that arrives with birth — a new beginning.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.