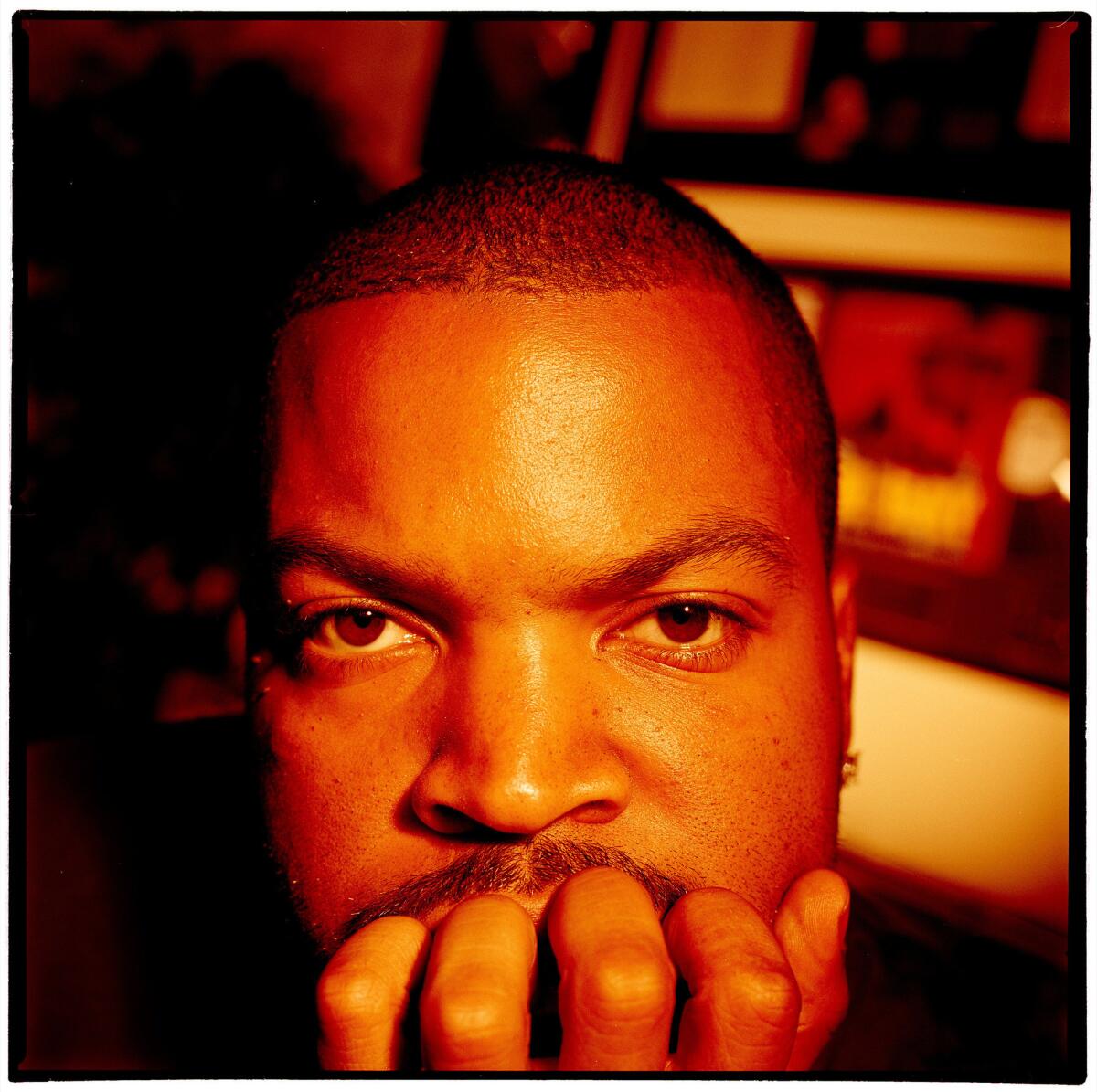

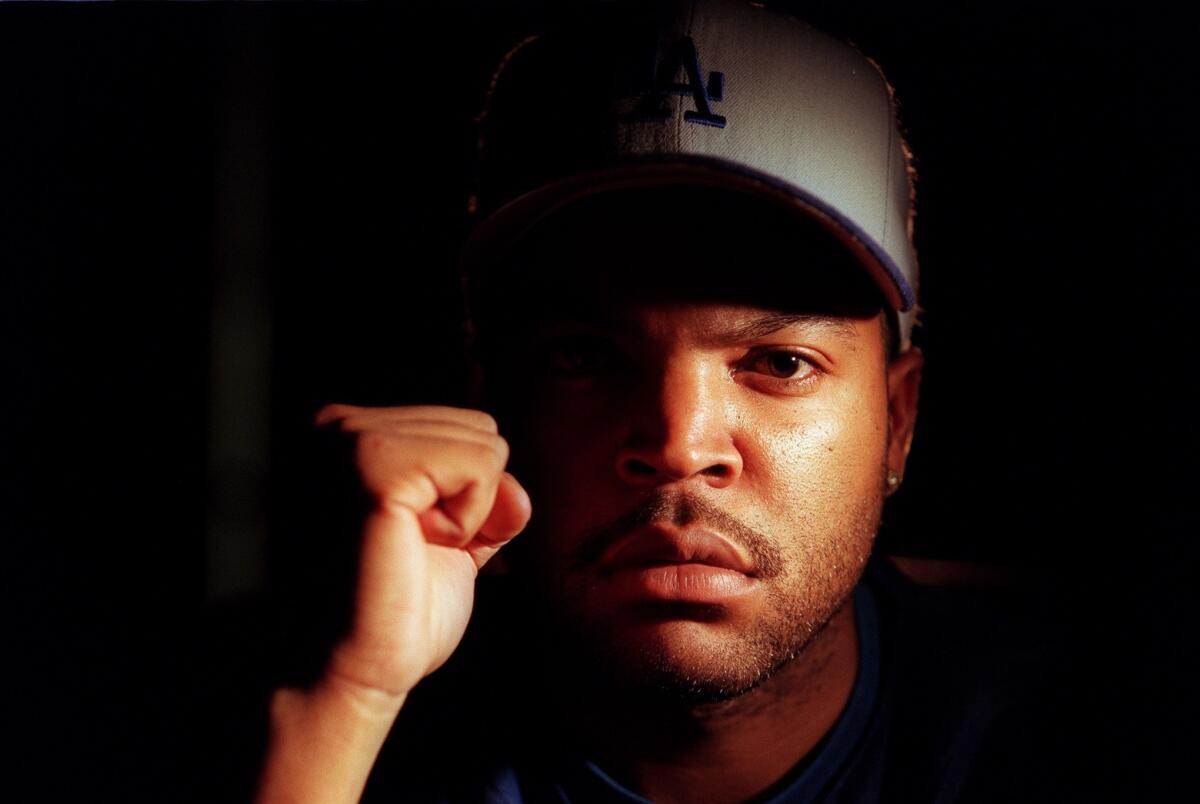

Ice Cube reflects on the 25 years since the release of ‘Death Certificate’

When George Holliday was awakened by commotion outside his home shortly after midnight on March 2, 1991, he jumped from his bed, grabbed his Sony camcorder and pointed it toward the chaos happening 90 feet away from his living room window.

The scene was shocking: A man being viciously beaten by a group of police officers. Holliday took the tape to KTLA and soon it was airing on national networks.The brutal beating of

For Ice Cube, the footage exposed the behavior he had already been rapping about.

“‘We finally got y’all … on tape.’ That was the feeling,” Cube thought when he saw the video.

I was making a transformation, mentally, from knowing street knowledge to knowing world knowledge.

— Ice Cube, on the creation of 1991's "Death Certificate"

At the time, Cube was a 21-year-old rap star hot from “Amerikkka’s Most Wanted” and “Kill at Will,” his first two solo projects after an acrimonious exit from

Cube was at work on material that ultimately would become his second full-length album, “Death Certificate.” King’s beating stirred him, with the incident coming at a moment when the young rapper was seeing the world differently after being exposed to the teachings of the Nation of Islam.

“I was making a transformation, mentally, from knowing street knowledge to knowing world knowledge — history, seeing things from a different perspective,” Cube said.

He wanted to channel that into the music, and he did with his sophomore effort, “Death Certificate.” Controversial on its release, the album gave voice to the perils facing young black men — be it systemic or self-inflected.

For Cube, there is no greater challenge than the relationship between black Americans and law enforcement, and it’s reflected in his latest single, “Good Cop Bad Cop,” one of three new songs on the reissue of “Death Certificate.”

The first project under a recently inked deal with Interscope is the 25th anniversary edition of “Death Certificate.” Released earlier this month, it launches what Cube hopes is the first in a series of anniversary releases for some of his most pivotal albums, with “The Predator” and “Lethal Injection” to follow.

Cube mined through the dozens of unreleased songs he had completed in some form and settled on a trio of tracks to polish for the project. “Good Cop Bad Cop” serves as the centerpiece of the reissue.

Built around a sample of N.W.A’s most incendiary cut, “… tha Police,” “Good Cop Bad Cop” is another polemic against police brutality. The fact that the reissue arrives during a time when the treatment of minorities by law enforcement has been a flashpoint of civil unrest across the country by a new generation of activists isn’t lost on Cube.

When [Marvin Gaye’s] ‘What’s Going On’ came out, I grew up loving it and … it’s still relevant. As artists to have some music like that, it’s what we live for.

— Ice Cube

“It’s the power of music. I was a baby when [Marvin Gaye’s] ‘What’s Going On’ came out, I grew up loving it and … it’s still relevant. As artists to have some music like that, it’s what we live for — making a statement and saying something that changes the world,” he said.

The record was split into two themes — the death side, a mirror image of where he believed we were at the time, and the life side, a vision of where we needed to go, the “we” being black America or, as he says, “the life that I was coming out of into the life I was trying to envision.”

“[He] really came out to stand up as an artist,” Cube’s longtime collaborator and friend, Sir Jinx, said of “Dearth Certificate.”

Released in October 1991, “Death Certificate” debuted at No. 2 on the U.S. pop chart before going platinum. The album is regarded as a rap classic and, arguably, Cube’s finest work. But it was also met with widespread backlash.

Everyone was subjected to Cube’s venom on the album: Whites, Korean grocers, police officers, gays, President George H.W. Bush,

“Do I have to sell me a whole lot of crack, for decent shelter and clothes on my back? Or should I just wait for help from Bush,” he asks on “A Bird in the Hand,” a record that tackles the limited options for many men in the inner city.

He railed against white supremacy on “I Wanna Kill Sam,” sneers at black “sellouts” on “Be True to the Game,” tackles gang warfare on “Color Blind,” stresses safe sex on “Look Who’s Burnin.’”

Then, on “Black Korea” he blasts Korean shop owners for perceived prejudices toward the blacks who frequent their establishments and promises violent retribution.

“Nobody is safe when you listen to ‘Death Certificate.’ Any of us that has any kind of flaws in our character, [the album] was probably going to find it,” Cube said.

Empowering and socially conscious messaging commingled with misogynistic, homophobic and bigoted posturing. It made Cube a confluence of contradictions.

Journalists repeatedly confronted him about the album’s content and questioned him on claims that he was anti-Semitic because of some of the lyrics on the scathing N.W.A diss track “No Vaseline.” One reporter went so far as to ask Cube how he would feel if someone shot a Jewish person after listening to the record.

A Village Voice review called Cube “a straight-up racist, simple and plain, and of course a sex bigot, too,” and Billboard penned an editorial condemning the rapper for “the rankest sort of racism and hate-mongering.”

There were calls for a boycott against Cube, particularly over “No Vaseline” and “Black Korea.” The Simon Wiesenthal Center, an L.A.-based Jewish human rights organization, implored national record chains to stop selling the album, and the National Korean American Grocers Assn. pressured the owners of St. Ides malt liquor to drop the rapper as their spokesman.

“It was much ado about nothing,” Cube said, downplaying the backlash. “At the end of the day it’s still music.”

A quarter of a century after “Death Certificate’s” release, Cube is still a razor sharp emcee, even though his work is met with far less scrutiny — an image no doubt tamed in part because of his prolific film career.

After enjoying a career as an independent artist, this spring he signed with Interscope Records. A logical move, he said, because the label oversees the catalog of music he distributed through Priority.

For its original production, Cube eschewed the melange of textures that was the signature of the Bomb Squad — the team responsible for his debut “Amerikkka’s Most Wanted” — for a heavy assortment of ’70s P-Funk and soul samples with production handled by the rapper, Sir Jinx, and the Boogie Men, the production team of Bobcat, Rashad and DJ Pooh (who would become one of Cube’s closest collaborators).

The reissue of “Death Certificate” is Cube’s first release since 2010’s “I Am the West.” He’s been teasing an album since 2013, but it’s often been pushed aside for film projects, including installments in his “Ride Along” and “Barbershop” franchises and last year’s blockbuster N.W.A biopic, “Straight Outta Compton.”

Outside of Hollywood and music, Cube’s Big3 basketball league just kicked off its inaugural season. Asked if he’s going to finish his long-gestating album, he answers in typical Cube fashion.

“I’m going to finish the record and put it out when I feel like it’s ready. It’s really about putting out something that’s great and not just because people want a record,” he said.

For more music news follow me on Twitter:@GerrickKennedy

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.