Some foggy nights in London town

Bright Young People

The Lost Generation

of London’s Jazz Age

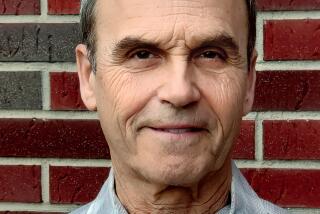

D.J. Taylor

Farrar, Straus & Giroux:

364 pp., $27

“Masked parties, Savage parties, Victorian parties, Greek parties, Russian parties, Circus parties, parties where one had to dress as somebody else, almost naked parties in St. John’s Wood, parties in flats and studios and houses and ships and hotels and night clubs, in windmills and swimming-baths,” wrote Evelyn Waugh in “Vile Bodies,” published in 1930. “Dull dances in London and comic dances in Scotland and disgusting dances in Paris -- all the succession and repetition of massed humanity. . . . Those vile bodies.”

Still in his mid-20s, Waugh finished this novel, his second, while an ill-fated marriage, his first, to Evelyn Gardner (known as “She-Evelyn”) was falling apart. “She-Evelyn,” who had been engaged some 15 times before she finally settled on Waugh, had run off with a man from the BBC. This last aspect of the matter was, for Waugh, an insult that only added to the injury and public humiliation; his wife was making a cuckold of him with a man who spoke on the radio.

Waugh responded with a hilarious yet increasingly despairing satire of the wild goings-on and giddy gaddings-about of the set to which he, his wife and her lover belonged -- a group known to eager London gossip columnists as the “Bright Young People” or “Bright Young Things.”

D.J. Taylor, an English novelist and the author of an excellent biography of George Orwell, takes this social grouping as the subject for his new book, “Bright Young People,” assembling the history and the particular social atmosphere behind the creation of Waugh’s anarchic fictive cosmos. The action plays out in the reckless years following one world war and preceding the economic cataclysm that would lead to another. The soundtrack here is the bongo beat of the Jazz Age, the settings switch between the streets and clubs of London and houses of ancient stone in the English countryside; the atmosphere is of doom and glamour.

And there are plenty of names: “Babe” Plunket Greene, Eddie Gathorne-Hardy, Bryan Guinness, the Honorable Hamish St. Clair Erskine and others who will chime a Monty Python-ish tone to some American ears, while remaining familiar to readers of British Vogue.

This alluring terrain, it has to be said, has been widely covered in biographies of Waugh and the poet John Betjeman, in chronicles of the preening dandy Stephen Tennant and the society photographer Cecil Beaton (who plotted his assault on the fortress of the high establishment with a more thorough ambition than Waugh himself could manage) and in the journals of novelist Anthony Powell (whose laconic, lapidary “Afternoon Men” is another exemplary fiction of the period). One also finds studies like Martin Green’s “Children of the Sun.” The Brits can’t get over this stuff. Waugh himself would return to the wellspring of his youthful decadence, fixing it in romantic myth in the golden early sections of “Brideshead Revisited.”

Taylor, however, brings plenty that’s new. Notably, he has been granted access to the family papers and photographs of the Ponsonby family. Arthur Ponsonby was an aristocrat who nonetheless joined the Labor Party and became a senior government minister; his wife, Dorothea, was the daughter of composer Hubert Parry. This pair had good reason to suppose that their children would in time assume expected positions in the society of which they themselves were pillars. That was the way England had worked. Instead, their daughter Elizabeth became the wildest and most lost of all the BYPs -- the model, in “Vile Bodies,” for the doomed, desperate Agatha Runcible.

Through the eyes of the Ponsonbys we watch Elizabeth take the starring role in a series of lurid newspaper headlines while blazing a comet-like trail of self-destruction. There’s the booze and the relentless round of parties; there’s a mock-wedding that hits the headlines, a real marriage that fails and a car crash that involves a fatality.

Dorothea diagnoses ennui: “It is a good deal that they are bored with Life & feel sapped -- drink rouses them & makes them feel cheerful once more. Their talk is mostly noise & laughter -- & the more noise they make the more successful they feel it is.”

Arthur, meanwhile, mourns his daughter’s rake’s progress, and, helpless to prevent it, blames himself: “I cannot see any way out at the moment,” he writes, noting another excess. “The House of Lords luckily acts as relief to ease the tension.”

These are familiar parental concerns and reproofs, no doubt; but by placing generational tensions and tenderness center-stage, Taylor gives his book a beating emotional heart. Elizabeth’s end is tragic, and her father feels for the rest of his life the “sharpest hurt”: “Hardly a day passes without my thoughts turning back to E and resulting in self-condemnation and desperate sadness.”

Taylor has a nice way with a one-liner -- “The books Brian Howard never wrote would fill a decent-sized shelf” -- and is excellent on the evolution of BYP argot, words like “bogus” and phrases such as “sick-making,” that Waugh adopted to give his early fiction and travel-writing its tang. “Miss Runcible said that kippers were not very drunk-making and that the whole club seemed bogus to her,” Waugh wrote, while Taylor tells us that Brian Howard (whose alter ego, Anthony Blanche, cuts a perfumed swath through “Brideshead Revisited”) inspected the baby of Bryan and Diana Guinness in its cradle and remarked: “My dear, it is so modern looking.”

Pointed language not only amused but also kept reality’s more painful aspects at a distance. In a wider way, Taylor’s study of the phenomenon of “brightness” gives us the development of the contemporary sensibility, a moment in history when Britain was ceasing to be an empire and becoming, instead, a cradle of pop culture. “Bright Young People” concerns the death-throes of one era and the painful birth of several others. People like Waugh and Cecil Beaton, “the middle-class meritocrats,” as Taylor calls them, had the last laugh, building careers out of the gorgeous wreckage they observed and forging a new establishment for others to press their noses against. Without Beaton, no Beatles, while Elizabeth Ponsonby’s antics remind one of Paris Hilton’s.

“Vile Bodies” can lay claim to being one of the funniest books ever written; it is also, in its representation of a crazy dash through a naughty adult playground the author knows will be condemned, extremely moral. Waugh was in despair when he wrote the book, and he responded with all the considerable wit and rage that were at his disposal. The fierceness that burns off the page is still unsettling.

In “Bright Young People” Taylor is writing splendid social history, not fiction, and he brings a more tempered and rueful approach, showing the sadness beneath an entire generation’s compulsion to waste its promise and dance in the spotlight. Scott Fitzgerald, a writer admired by Waugh (who was no soft touch), called his own “lost” contemporaries “the beautiful and damned”; here, Taylor makes us feel the full force of the reckoning implied in that sad conjunction.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.