‘Something in the Air’ by Richard Hoffer

In the summer of 1968, events were roiling America and the world: the assassinations of Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert F. Kennedy; the escalation of the Vietnam War; the Soviet Union’s invasion of Czechoslovakia; the radicalization of the civil rights movement.

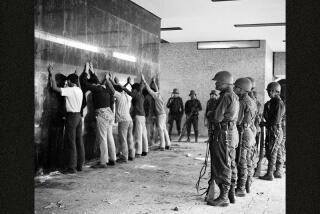

The tenor of the times consumed and overshadowed the competition at the Mexico City Olympics. Indeed, the ’68 Games will forever be defined not by Bob Beamon’s gravity-defying long jump, but by the black-gloved demonstration of sprinters Tommie Smith and John Carlos and the killing of protesting students by the Mexican police and army 10 days before the opening ceremonies.

Until recently, Berlin (1936, Hitler’s Games) and Munich (1972, the Black September terrorist attack) have generated the bulk of Olympics-related literature. Mexico City is gaining ground, jump-started by two academic-press books this decade: Amy Bass’ “Not the Triumph but the Struggle: The 1968 Olympics and the Making of the Black Athlete” and Douglas Hartmann’s “Race, Culture, and the Revolt of the Black Athlete: The 1968 Olympic Protests and Their Aftermath.” Both Smith (“Silent Gesture”) and Carlos (“Why?”) have also written autobiographies.

Now comes Richard Hoffer’s “Something in the Air: American Passion and Defiance in the 1968 Mexico City Olympics.” A longtime Sports Illustrated writer, Hoffer is known best for his boxing coverage. Whether explicating the phenomenon of Mike Tyson or the marketing push behind Oscar De La Hoya, Hoffer never let bluster or subterfuge (the old one-two of the sweet science) interfere with astute reportage.

In “Something in the Air,” Hoffer introduces us to a large cast of characters in bite-sized pieces. Many are familiar faces, including miler Jim Ryun and boxer George Foreman. (Hoffer’s description of Foreman’s journey from street thug to gold medalist is richly detailed.) Others are probably forgotten by those who do not follow track and field: Dick Fosbury, who revolutionized high jumping; sprinter Wyomia Tyus; quarter-miler Lee Evans; USC pole vaulter Bob Seagren.

Athletics aside, the most compelling story from Mexico City remains race. San Jose State sociology professor Harry Edwards, himself a former athlete, broached the idea of a boycott by African American athletes at a meeting in Los Angeles in 1967. He knew that a boycott of the Olympics would devastate the U.S. team and count as a propaganda victory for the U.S.S.R. “It’s time for black people to stand up as men and women and refuse to be utilized as performing animals for a little extra dog food,” Edwards said. In connecting sports to the civil rights movement, Edwards and his allies spotlighted hypocrisy on the playing field. Many Southern universities did not give scholarships to African American athletes. In the professional ranks, there were no black managers or head coaches. Muhammad Ali had been stripped of his heavyweight title because of his refusal to fight in Vietnam. (SI staffer Jack Olsen’s groundbreaking, five-part series drew attention to the plight of the black athlete in 1968.)

As Hoffer points out, few athletes chose not to compete. In Mexico City, African American athletes won seven of the 12 U.S. men’s track and field gold medals; black U.S. women, who were not consulted about the potential boycott, won three golds. Smith and Carlos finished one-three in the 200-meter sprint (with Smith using his “Tommie Jets” to shatter the world record). After the race, they mounted the victory podium in black socks and, as the National Anthem played and the American flag was raised, thrust fists into the night.

Their eloquent, silent defiance outraged Avery Brundage and his minions on the International Olympic Committee, whom Hoffer describes as “a cadre of old white men redolent of their privileges.” The IOC pressured the U.S. team to exile Smith and Carlos. The pair were vilified by, among others, Brent Musburger, who called them “dark-skinned storm troopers.”

Hoffer provides a livelier alternative to Bass and Hartmann’s accounts. However, he falters by expending little effort in placing the Games in historical perspective. He describes the so-called Tlatelolco Massacre, during which the Mexican government killed perhaps hundreds of protesting students, but never returns to the still-controversial topic. The use of steroids is mentioned in passing, even though it was becoming obvious that athletes were indulging. He summarizes Smith and Carlos’ post-1968 lives in two paragraphs -- their tortuous tale is worthy of its own chapter, not least because Carlos wrote in his autobiography that he allowed Smith to win the 200. Smith has countered that Carlos did not deserve selection to track’s Hall of Fame. Meanwhile, in a neat reversal, they’re now perceived as heroes, with a statue of their gesture erected on the San Jose State campus.

Yes, there was something in the air in Mexico City: the realization that sports and the Olympics were not immune to politics and social change. Hoffer captures a fleeting glimpse of this new order, one that four years later would haunt Munich with deadly consequences.

Davis is a contributing writer at Los Angeles magazine.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.