‘Kafka Fragments’ at Walt Disney Concert Hall

May we please stop obsessing over the hypoallergenic first puppy and change the subject to something deep, spiritual, life-changing? Like detergent.

Sunday night, President-elect Barack Obama, appearing with his wife, Michelle, on “60 Minutes,” spoke of household chores. He doesn’t, he admitted, volunteer to wash dishes, but he washes them. And when he does, he said, he tries to use that as therapeutic practice, to find something soothing in the discipline.

Almost as if on cue, Tuesday night Dawn Upshaw got out the Dawn. The soprano put on rubber yellow gloves with satisfying pizzicato snaps and got down to the business of cleansing her soul. Upshaw washed dishes on the Walt Disney Concert Hall stage. And in doing so, and quite a bit more that took her to the brink of sanity and back more than once, she offered one of the great musical and dramatic performances of our time.

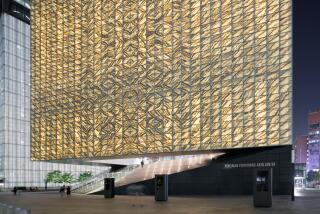

The occasion was a presentation of György Kurtág’s “Kafka Fragments,” in Peter Sellars’ staging, as the opening concert of the Los Angeles Philharmonic’s Green Umbrella series this season. A setting of 40 fragmentary texts taken from Kafka’s diaries, notebooks and journals, this work for soprano and violin all but defines claustrophobia in music.

That the meaning of the miserable life is not misery, that being is nothingness and that that is something is, more or less, the existential subject matter. Pleasure for Kafka became pain, and pain, perversely, pleasure. “Once I broke my leg,” he wrote in one fragment, “it was the most wonderful experience of my life.” “Coitus as punishment for the happiness of being together” is another fragment.

Kurtág’s settings can be bleak, and a fragment can pass by with minimal notes in as few as 13 seconds, lest unspeakable emotions be spoken. Yet Kurtág will also go to the other extreme, with so many notes that overwrought emotions drown out the meaning of words and become brute bellow. There is, for this haunted composer -- soul mate of Kafka, Beckett and Dostoevsky -- no middle ground. The violin part might fixate on two notes or it might gyrate madly as if meant for a demonic Transylvanian folk fiddler.

Sellars introduced his radical staging of these fragments for Upshaw and violinist Geoff Nuttall (the first violinist of the St. Lawrence String Quartet) in Carnegie Hall’s small Zankel Hall in January 2005. Dressed in old clothes, the soprano cleans house -- ironing, scrubbing the floor. She gets out a stepladder and some cord and hangs herself. She burns her face with her iron. When Kafka describes leopards breaking into the temple and drinking the sacrificial jugs dry, Upshaw, possessed of an animal spirit, licks the wash basin dry.

The performance nearly four years ago was shattering, as soul-searching for the audience as for the performers and a new peak in the career of an ever-evolving soprano. But much has changed since. Upshaw has undergone cancer treatment and returned to the stage an even more intense artist. Tuesday night, she reached yet another new height, and Sellars’ production found more depths in this masterpiece.

Sellars designed the staging for a small hall in which onlookers become uncomfortable voyeurs. In Disney, Upshaw sang to the masses (attendance was approximately 1,000). She amplified expression, and the result was even more shocking.

The smallest sounds could be heard without her having to force her voice. But she had plenty of space, which allowed her to project more boldly than I have ever heard her do, to throw herself into the music, to shriek out her lungs when asked to. Kurtág’s screams reached the mountaintop. She sounded spectacular.

In the production, Sellars employs stark projections of black-and-white photographs by David C. Michalek that reflect images from the text, and they looked stunning in Disney. The violin part is as demanding as the soprano’s. In the earlier version, Sellars made Nuttall a dramatic alter ego of Upshaw. Now he remains more in the background, a musical and spiritual anchor. He played extraordinarily well.

James F. Ingalls designed squares of light that served to both define the playing space for the performers and frame them in the context of the hall. It was a brilliant solution. But then everything about “Kafka Fragments,” from Kurtág’s smallest musical setting to Upshaw’s incendiary singing and acting, was a brilliant response to the most pressing issues of existence.

mark.swed@latimes.com

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.