Dudamel conducts Strauss and Beethoven with Los Angeles Philharmonic

At the end of a long and full life, Richard Strauss wrote four songs for soprano and orchestra. Born in 1864, he weathered two world wars, remaining on the German side for both.

The English titles are “Spring,” “September,” “Going to Sleep” and “At Sunset,” and they were published after Strauss’ death in 1949 as “Four Last Songs.” Little music of the last 60 years is as beloved by concert audiences. The Los Angeles Philharmonic first programmed the songs in 1955 with Elizabeth Schwarzkopf as soloist.

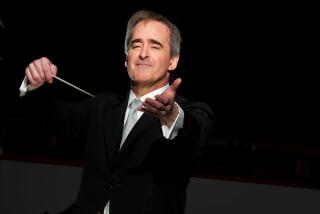

Friday night, Gustavo Dudamel led a performance of “Four Last Songs” with the orchestra and soprano Christine Brewer in the Walt Disney Concert Hall. He is 27. At that age, Strauss too had already been a sensation -- by 27 he had written “Don Juan” and “Death and Transfiguration.” A half-century wiser, he took transfiguration out of the death equation.

What 57 more years’ experience might bring to Dudamel, no one, of course, can imagine. His life is now that of a young musician’s great adventure, as he conquers the globe. He wins over orchestras and audiences through the expression of an irresistible life force. He makes the young feel good and the old feel young.

Brewer filled the hall Friday with a robust sound that mixed sweetness, power, glory and consolation -- a thrilling combination. Dudamel did not linger over dying embers. He brought out details in the orchestration, shaped small gestures exquisitely and handled the sweeping Straussian gestures like a pro. He has a proclivity for composers’ late style and is a deep and serious interpreter. But these are songs no conductor can prepare for -- life first has to be led.

The authentic adventures were elsewhere on this program, which began with Ligeti’s “Atmosphères” and ended with an arresting account of Beethoven’s Sixth Symphony, the “Pastoral.”

Ligeti’s short score is still called new music, although it was written in 1961. A work of liquidly contrapuntal lines that fuse into orchestral clouds, it helped usher in “Space Age music” when Stanley Kubrick used it in 1968’s “2001: A Space Odyssey.”

Dudamel’s performance was a lyrical, lushly sensual sonic odyssey. Written 20 years before he was born, the score is not really new music for him or, for that matter, the orchestra (which first played it in 1971). His approach was to treat Ligeti as a finely grained classic. What was special here was Dudamel’s dynamic control, which was mesmerizing, as he brought the orchestra to the edge of audibility and then held it there for a while.

Dudamel’s first recording was of Beethoven -- the Fifth and Seventh Symphonies -- with his Simón Bolivar Youth Orchestra of Venezuela. Released two years ago, that bestselling disc was the beginning of Dudamania. Last season, he led Beethoven’s Fifth with the Bolivar, around 150 strong, in Disney. Fate supposedly knocks on the door in the Fifth. Dudamel broke the door down, his young band swaying like trees in a hurricane.

The “Pastoral,” Beethoven’s hymn to nature that was written at the same time as the Fifth, has an actual musical depiction of a storm, and Dudamel’s arresting ferocity was again on display.

A professional orchestra, even America’s most versatile one, is not going to rock and roll its way through Beethoven the way those Latin American kids do. Moreover, Dudamel chose here to use a moderately sized band, as is the norm with Beethoven performances these days. But the Philharmonic was on fire, and the “Pastoral” was, in its own way, no less bold Beethoven than Dudamel’s Fifth.

So I am happy to report that this wasn’t a perfect “Pastoral.” It didn’t entirely hold together. If it had, Dudamel, at 27, would have no place left to go, and we would have nothing to look forward to when he takes over as music director of the Philharmonic next season.

The performance did have this: In the fast movements, the orchestra was about as animated as it has ever been. As the strings let rip, normally poker-faced players smiled, as if energized by the chase. But Dudamel also let Beethoven’s sunniest lyricism glow. Ariana Ghez’s oboe solos brought the outdoors in.

What Dudamel’s interpretation lacked, for all its edge-of-the-seat drama, was a sense of release, a notion of a mystical Nature, of Beethoven’s benediction over the land.

But we can wait.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.