Discoveries

The Paper Garden

An Artist Begins Her Life’s Work at 72

Molly Peacock

Bloomsbury: 416 pp., $30

Mary Delany was born in 1700 to an upper-class family in England that would fall out of favor with the court and use its lovely young daughter, as so many families did at the time, to marry itself back into money. Elderly, alcoholic Alexander Pendarves came with a castle, and Mary endured her marriage to him by writing letters to her sister and surrounding herself with clever friends such as Jonathan Swift, Samuel Richardson, Hogarth and Handel.

Years after Pendarves died, Mary’s passionate life began with an Irish clergyman named Delany. But it was not until his death, after years of suffering, that she began creating the startling paper collages, intricate mosaics — flowers cut from paper, thousands of them, that now survive her in the British Museum and in books. Molly Peacock discovered Mary after an exhibit of her work at the Morgan Library in New York. She became a role model for Peacock, a way to understand her own life and a way to grow old with dignity. This book layers Delany’s life and work over Peacock’s. It is organized by flower — forget-me-not, thistle, poppy, etc., each a metaphor for a different phase in Delany’s life. In this way, the book itself is a complicated, delicate and beautiful collage. “If a role model in her seventies isn’t layered with contradictions,” Peacock writes, “as we all come to be — then what good is she? Why bother to cut the silhouette of another’s existence and place it against our own if it isn’t as incongruous, ambiguous, inconsistent, and paradoxical as our own lives are?”

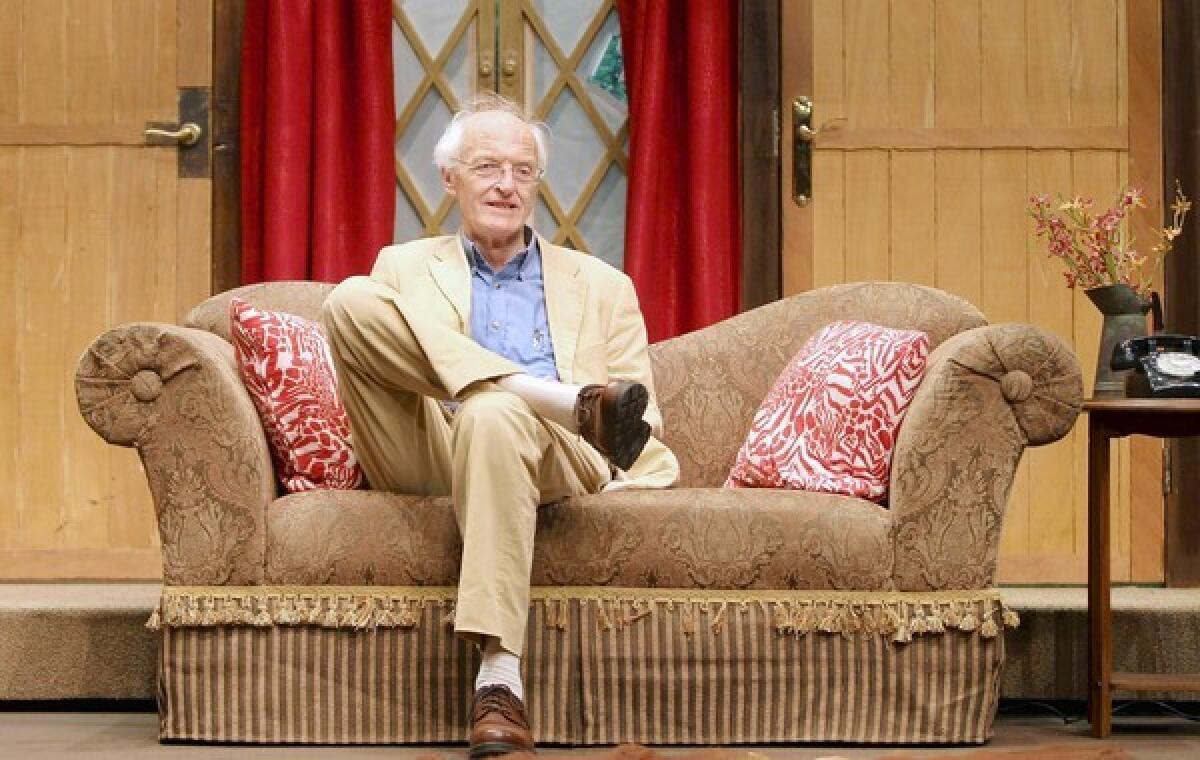

My Father’s Fortune

A Life

Michael Frayn

Metropolitan Books: 273 pp., $25

It doesn’t seem possible — playwright and novelist Michael Frayn’s father, Tom, born in 1901, grew up in a family with two deaf parents and three deaf siblings. Tom Frayn became deaf in middle age. His son, Michael, has written 10 novels and some 16 plays. “My Father’s Fortune” is a memoir muttered under the author’s breath — he talks to himself, asks himself whether he is exaggerating, whether his memory is playing tricks. His father emerges from these pages as a character in a black homburg, mysterious and loving.

The son disappoints — he can’t play cricket and he’s slow-witted. He remembers his mother, Vi, and tries to reconstruct his parents’ happy marriage. He remembers the sounds of bombs at night in 1944, when he was 11, and his mother’s death soon after the war. Frayn blinks at each new detail of his father’s life and even his own — the way we feel looking back at our own lives with wonder. So that’s why we did that! So that’s how we really felt! His father’s frugality, his life as an asbestos salesman, his patience and his grief all merge. And with these memories, a little guilt — why can’t we feel more, express more when the people we love are still living?

Shadows Bright as Glass

The Remarkable Story of One Man’s Journey From Brain Trauma to Artistic Triumph

Amy Ellis Nutt

Free Press: 272 pp., $26

Jon Sarkin was torn, from childhood, between a career in medicine, like his father, and the life of an artist. He chose medicine and became a chiropractor. One day in 1988, when Sarkin was 35, golfing with a friend, he felt a sudden twinge in his brain like a switch had flipped. In fact, it had. A blood vessel had shifted, touching his eighth cranial nerve. He was dizzy and disoriented. After months of excruciating tinnitus and unsatisfactory visits to various specialists, Sarkin had deep brain surgery, which brought on a stroke. He emerged from the stroke like a blank canvas, and slowly a new self emerged — the soul of an artist. Sarkin painted obsessively and now, decades later, is an acclaimed artist. (Tom Cruise has purchased the rights to his story.) Amy Ellis Nutt, a journalist, interweaves Sarkin’s astonishing story with similar stories of brain trauma and broken identity throughout history. She brings us into the ever-changing world of neurobiology and the slower world of exploration into the nature of self and the soul. Nutt gives us so much to think about — the nature and sources of creativity, the soul and destiny, the strange identities we sometimes wrongly cling to.

Salter Reynolds is a Los Angeles writer.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.