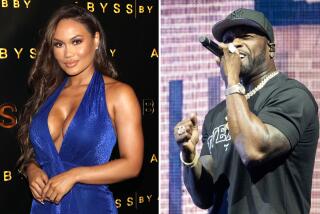

Not Just for Kids: ‘Playground: The Mostly True Story of a Former Bully’ by 50 Cent

Playground

The Mostly True Story of a Former Bully

50 Cent with Laura Moser

Razorbill: 242 pp., $18.99, ages 12 and up

The boy who grew up to be the gangster-rap superstar 50 Cent has been more than open about his troubled youth. Raised by a single mother, who dealt cocaine and was murdered when he was just 12, 50 Cent started dealing drugs and carrying guns in middle school.

But that isn’t the story he tells in his young-adult debut, “Playground: The Mostly True Story of a Former Bully.” The fictional account of a 13-year-old’s descent into bullydom is loosely based on 50 Cent’s personal experience, only softened. Incorporating enough urban grit to be believable but otherwise smoothing off the rough edges of inner-city teendom to appeal to a young and mainstream audience, 50 Cent mines the situational psychology of a child who resorts to intimidation and violence.

As a genre, young adult fiction is teeming with “issues,” but few are as topical as bullying, which many health professionals now view as an epidemic. Part of the solution to any epidemic is understanding it. And in that regard, 50 Cent is doing a great service to readers by leveraging his from-the-streets credibility and experience as a bully to explore how it can happen.

The 36-year-old rap artist has sold more than 22 million albums and earned 12 Grammy nominations, but as he notes in the book’s introduction, “not everything I’ve done in my life has been role-model material. I’ve been on the wrong side of the law. I’ve been in violent situations. I’ve also been a bully. I know how a person gets to be like that. That’s why I wanted to tell this story: To show a kid who’s become a bully — how and why that happened, and whether or not he can move past it.”

Like his music, which draws upon 50 Cent’s rise from the streets, “Playground” also derives from experiences in his childhood and adolescence with an emotionally driven lead character named Butterball. So called because of his weight, Butterball is a seventh-grader whose parents split up a couple of years earlier, forcing him to divide his time between his dad’s place in New York and his mom’s apartment in the Long Island suburb where he goes to junior high. Told from Butterball’s perspective, the story opens in a psychologist’s office, where the overweight teen is sent twice a week to talk about why he smashed the face of a classmate with a sock full of D batteries.

His voice is slang-y, profane, defensive. His attitude is condescending toward authority and remorseless as an aggressor. In therapy, Butterball thinks the doctor is “stupid,” “skinny” and has “zero taste.” Beating up the boy he once considered a friend felt good, he admitted. It was the rare time he’d felt respect from his peers — or gotten much attention from his parents.

His mom works double time as an orderly and is also going to nursing school. His dad makes more time for his girlfriends than for his son. These details are casually dropped into the narrative as a backdrop to the action, which has Butterball progressing through his days like so many other disenfranchised teens. School isn’t for learning so much as escaping what’s happening at home. He goes through the motions of his days without any real effort or learning or connections.

There is, of course, the out-of-reach love interest, but there aren’t any real friends. Instead of facing that sad reality, Butterball eats lunch in the handicapped stall of the boys’ bathroom. His only aspiration is a new pair of $300 cobalt-blue sneakers.

“In some jack way, I was kinda relieved” he admits after a few weeks of seeing his therapist.

The therapeutic narrative of “Playground” is somewhat cliche, but it serves its purpose. Butterball’s therapy offers insight into a behavior that few bullies, or their victims, understand. And it shows a path forward that is proactive and redemptive. While few bullies will grow up to be anywhere near as successful as 50 Cent, “Playground,” at least, offers hope.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.