L.A. Opera goes for laughs with ‘Albert Herring’

The showbiz adage that dying is easy, comedy is hard applies to opera as well. Though there are plenty of great comic operas — including Rossini’s “Barber of Seville” and “The Turk in Italy” and Donizetti’s “Elixir of Love” and “Don Pasquale,” all presented by L.A. Opera in the past — their number pales next to the multitude of melodramas that more frequently occupy the operatic stage.

“Comedy is extremely difficult,” said Paul Curran, whose Santa Fe Opera production of Benjamin Britten’s comic opera “Albert Herring” opens at L.A. Opera on Feb. 25. “It requires more concentration and skill than anything else. Tragedy is easier. You need to be very inventive with comedy.”

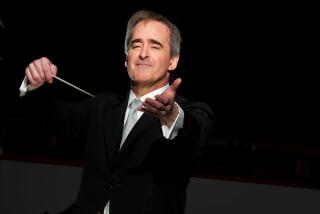

L.A. Opera’s music director James Conlon, who will conduct the production running through March 17, agrees with Curran. “I’m not prepared to say there’s not enough comic opera,” Conlon said. “But proportionally there are more great melodramas in every era. Comedies are harder to write, harder to get right and harder to produce. And a bad performance of a comedy dies a death that is much worse than a bad performance of a melodrama. Every moment of a comedy has to be constructed correctly. Otherwise, it doesn’t work.”

“Albert Herring,” which had its premiere in 1947 at England’s Glyndebourne Festival, came relatively early in Britten’s career, quickly following his masterwork “Peter Grimes” and the less-successful “The Rape of Lucretia,” both dark pieces. But “Herring” was not Britten’s first light work for the stage. That would be the seldom-performed “Paul Bunyan” — more musical theater than opera — which enjoyed its first performance in New York in 1941 as Britten, a lifelong pacifist, was riding out World War II in America.

“It’s the odd man out, as is its protagonist,” said Byron Adams, a professor of musicology at UC Riverside and an expert on 19th and 20th century British music, speaking of “Herring” and its unusual position as a comedy in the composer’s canon of operas that deal variously with suicide, rape, murder, pedophilia and all manner of psychological abuse.

“He had done ‘Paul Bunyan,’ which was a lighthearted piece that flopped,” Adams added. “Then came ‘Peter Grimes,’ which was a huge success, and ‘The Rape of Lucretia,’ which was not such a success. I think at this point Britten feels he needs a comic opera.”

Curran concurs. “In 1947, the war was only over for two years, and nobody was writing deeply serious works,” the director said. “This was about trying to find a lighter side of life. It’s a full-blown comedy with a serious line through it: allowing ourselves the liberty of experience.”

Loosely adapted from Guy de Maupassant’s short story “Le Rosier de Madame Husson” (“Madame Husson’s Rose King”), Eric Crozier’s libretto relocates the action from France to England, where Albert Herring (sung by tenor Alek Shrader), a meek provincial greengrocer’s son finally, and rather suddenly, comes of age. But that thin plot is merely the frame on which Britten and Crozier hang a richer portrait of English country life, complete with broad satire of the upper classes, the church and the parochialism that characterizes the goings on in a small town.

“I love the opera for its hilarity, for its social commentary,” Conlon said. “It makes the public laugh. And while it makes them laugh, it deals with the same subjects Britten dealt with previously and would continue to deal with: youth and innocence, social inequality, the aspiration of an individual in an environment that often oppresses him. In that regard, ‘Albert Herring’ is as serious as ‘Peter Grimes.’ The characters in ‘Albert Herring’ — the vicar, the schoolteacher Miss Wordsworth, the police superintendent, Mayor Upfold, even Lady Billows — all could have walked out of ‘Peter Grimes.’ The difference is that at the end we’re going to smile, whereas in ‘Grimes’ we’re going to suffer.”

That blurring of the divide between comedy and drama, however slight, has likely increased the opera’s appeal on both sides of the stage. Curran certainly welcomes the opportunity for shading and in that spirit invokes a comparison with Richard Strauss. “When Strauss was asked why he wrote ‘Der Rosenkavalier’ after ‘Elektra,’ he said it was like Mozart’s ‘Marriage of Figaro.’ There’s not much to laugh at in ‘Figaro,’ but there’s plenty to smile about. ‘Albert Herring’ makes me laugh but also smile as well. Britten digs into relevant and deep human stories. It’s about a lighter subject taken very seriously.”

One aspect of the opera that continues to engender debate is its somewhat cryptic conclusion. After having gone missing, Albert suddenly reappears with enough self-confidence to sever the apron strings that had tied him to his overbearing mother (sung by mezzo-soprano Jane Bunnell).

“So all of a sudden he becomes a person in the last scene?” Adams asked. “After a few beers and a night in the field? Come on! This is a coming-out story by a composer who never came out. But you can’t show that. The only way this disaster of an ending could happen is for Albert to come back on the arm of a handsome guardsman with his tunic unbuttoned. It’s a piece whose real message is hobbled by its time.”

Curran takes a less doctrinaire approach. “I think the opera is more innocent than that,” he said. “It’s about a young man discovering his sexuality, whatever that may be. If there’s any message, it’s: follow your heart. But I don’t see it as a gay story.”

For his part, Conlon maintains that the opera should end in a manner similar to Mozart’s “Così fan tutte.” “You’re not quite sure about everything that went on that night, and you don’t know what the future holds,” the conductor said. “I want Albert Herring’s future to be a question mark, a matter of conjecture.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.