Collapsing worlds

THIS story, as most stories do, starts out in simpler times.

In London in mid-2001, at a performance of the Neil LaBute play “The Shape of Things,” director Darren Aronofsky stopped backstage afterward to meet its star, Rachel Weisz.

“It was a professional meeting,” he recalls. “It’s a good thing for actors to meet directors and directors to meet actors, plus her performance blew me away. So we went out to dinner. I remember it was traditional English food -- jellied eels, weird stuff. The next day, we actually went on a spontaneous date ... we went down to Brighton and walked around and had an incredible day. And then we had an e-mail correspondence for a long time. I also sent her a copy of the script -- ‘This is what I’m working on’ -- and she really liked it.”

The script has become Warner Bros.’ epic sci-fi adventure “The Fountain,” which is finally getting its release on Friday, five years later. At the time, it was budgeted at $70 million and was to star two of Hollywood’s biggest: Brad Pitt and Cate Blanchett. Aronofsky’s 1998 debut, “Pi,” made on a shoestring, was a cerebral, paranoid thriller grounded in “the Kabala, the stock market and mystical math” as he itemizes its ingredients, but Cuisinarted together. Its follow-up, an adaptation of Hubert Selby Jr.’s cult novel “Requiem for a Dream,” calibrated its Bowery gothic junkie milieu with a postmodern mix of fractals and beats per minute.

With “The Fountain,” working on economies of scale, he would combine an interest in Maya archeology with research in primate cognition being conducted by his old Harvard roommate, Ari Handel. Handel was then getting his PhD in neuroscience at New York University and questioning the ethicality of his experiments on monkeys (which he would soon leave behind for the moral palate cleanser of the film industry).

The two took long walks around Aronofsky’s native Brooklyn, where his father had been a high school science teacher, and steeled by an early viewing of “The Matrix,” they resolved to reinvent science fiction as free from computer-generated imagery, which could date a film’s look in a mere six months, as well as the retro-futurist high-tech fetishization that Aronofsky labels “trucks in space” -- basically “Pimp My Ride” for flying saucers.

For good measure, they reconfigured the time-space continuum with a palindromic structure: Three time periods that each fold into and out of the others, like Russian dolls or Chinese boxes. In 1500, Queen Isabella sends conquistador Tomas Creo (Spanish for “I believe”) off to the Maya empire in what is modern-day Guatemala to find the fabled Tree of Life from the Book of Genesis -- the eponymous Fountain of Youth. In 2000, a neuroscientist, (Tommy) labors to find a cure for his wife’s cancer (here named “Izzi” -- a palindrome), achieving a cryogenic breakthrough using a Guatemalan compound. In the third, (Major) Tom, floating in a lotus position at the center of a glistening bubble, far above the world, transports the Tree of Life to the dying star Xibalba, the pathway to the Mayas’ realm of the dead. As the characters repeat, similar imagery recurs fugue-like throughout, and everything becomes a clue.

“It was always meant to be a poem, because it’s a very visual film, and it’s dealing with these really huge issues,” Aronofsky says. “It’s asking the biggest questions that are out there -- about reality and existence and consciousness, about which there are no answers. So for me, it’s always been about constructing a puzzle that intellectually you’re putting together in your head, but emotionally hopefully you’re being affected by the character’s journey.”

The results, depending on your tolerance for metaphysics as a substitute for narrative logic, may either be the Mesoamerican equivalent of the last third of “2001: A Space Odyssey,” with the Maya god-king Ruler II as your spirit guide, or else a mash-up of historical epic and late-sequel “Star Trek” -- a kind of “Aguirre: The Wrath of Khan.”

Over six years of struggle, the filmmakers were forced to wait out Blanchett’s pregnancy, only to have Pitt leave the project after two years; investors pulled out (Regency eventually replaced Village Roadshow to partner with Warner Bros.); and the epic Maya battle they had envisioned to open the picture was rendered obsolete by “Lord of the Rings,” “Troy” (starring Pitt) and countless others. The budget, which had ballooned from $30 million to $70 million, reverted to $30 million. Again, a palindrome.

But all of that came later.

Months after they first met, late on the evening of Sept. 10, Weisz arrived in Manhattan for the New York run of “The Shape of Things,” while Aronofsky flew to Los Angeles on business, missing her by hours. The next morning, still jet-lagged, she took an early-morning jog by the World Trade Towers, making it back to her Canal Street hotel just in time to feel the impact of the first plane. It was several weeks before Aronofsky could get a flight back, and as he explains it, they’ve been together ever since.

“I want to go with that story, I’m feeling it, but it wasn’t really like that,” says Weisz, ruining a perfectly good tale. “It wasn’t like he came running back into my arms. I would say that I fell in love with Darren before he fell in love with me. I assumed he would be a pretty weird, dark, intense, bizarre person, and instead he has this lightness of spirit. I would describe him as a person who was very good at life. So I would say I chased him.

“Also, the culture he comes from -- this Brooklyn Russian culture -- is very exotic to me. I think we’re probably exotic to each other. To some English bloke, I’m pretty banal.”

The offspring of a Hungarian father who invented a pneumatic respirator still in use today and an Austrian therapist mother, Weisz grew up in posh London surroundings, attending private school and modeling during her summers. She entertained early ambitions of being a private detective before earning an English degree at Cambridge, where she spent most of her time immersed in her own avant-garde theater company, a kind of two-woman Wooster Group called Talking Tongues.

Of her parents, she says, “I would say they’re both dreamers. In our family, the future just comes and hits you in the forehead.”

From the beginning, Weisz and Aronofsky vowed they would not work together, preferring to live their lives instead. And yet with each new hurdle in the history of the production, it was invariably Weisz who retained faith in the project. She accompanied him to Australia when he had to fire the entire crew following Pitt’s departure. (Aronofsky goes to some lengths to emphasize that Pitt behaved honorably throughout.)

Another chance backstage encounter -- this one with Hugh Jackman after his Broadway tour de force in “The Boy From Oz” -- led to him being cast as the male lead, and it was Jackman who forced the issue, constantly asking, “What about Rachel?” and demanding that she be allowed to audition.

Weisz reports the couple lived apart during the filming, seeing each other only at work and on the weekends. Accepting the Oscar last year for her performance in “The Constant Gardener,” Weisz was seven months pregnant, and in April gave birth to their first child, Henry Chance Aronofsky. “It’s a magical word,” says Weisz of his middle name. “I guess chance is magic, isn’t it?”

Not surprisingly, Aronofsky thinks Weisz is “spectacular in the film.”

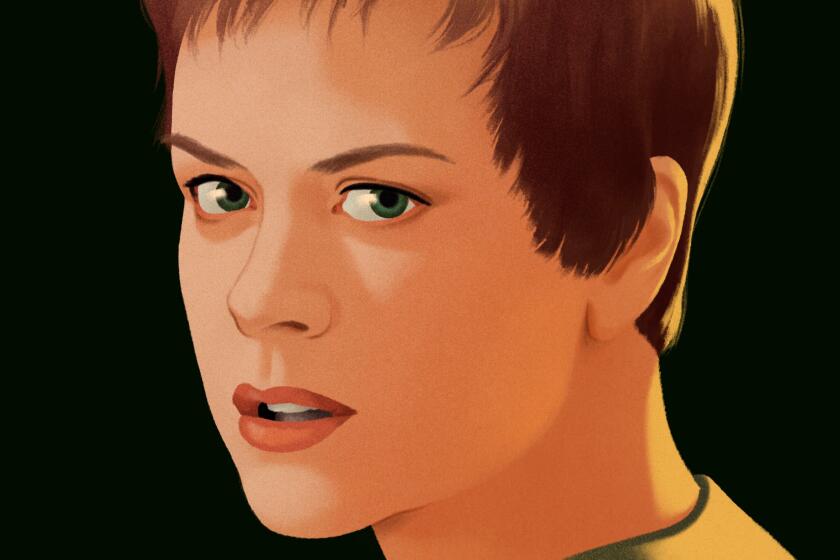

“The way she looks and the way she captures that timelessness, her beauty. What I like about Rachel is her complexity. Like a diamond, there are so many different facets to her.”

“For me,” Weisz says, “what the whole movie is about is when Izzi says to her husband, ‘Come take a walk with me,’ and he says, ‘I’m too busy.’ The film asks the question: What if we could live forever? But the answer is that life is finite and short, and therefore must be treasured. Every moment is a miracle...

“I’m impressed that someone would have the tenacity and the passion to stand by what they believe in and make a dream come true. To make this crazy, mind-bending story come out. I’m sure I helped support him sometimes, but really it was his journey. If it had been me, I’d have given up, without a doubt. And I felt very privileged to watch that happen.

“It was a bit of a fairy tale really.”

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.