Book review: ‘Great House’ by Nicole Krauss

GREAT HOUSE

A Novel

Nicole Krauss

W.W. Norton: 290 pp., $24.95

Maybe it’s because I am a father, but to me the most resonant sections of Nicole Krauss’ widely anticipated third novel, “Great House,” are those narrated by Aaron, an aging Israeli who still hasn’t figured out how to relate to one of his adult sons. Aaron is bitter, loving, angry, complicated — “full of passionate intensity,” to borrow a line from Yeats. He is, in other words, a real person, marked by pride, regret and secret longings, which make him the most three-dimensional presence in the book. The two chapters he narrates pulse with his hot-blooded heartbeat; the drama of his family rises to the level of the epic because he makes it so. As for the rest of the novel, it’s well done enough, nicely written and full of cogent insights, but compared with Aaron, it feels as if it’s taking place behind a sheet of glass.

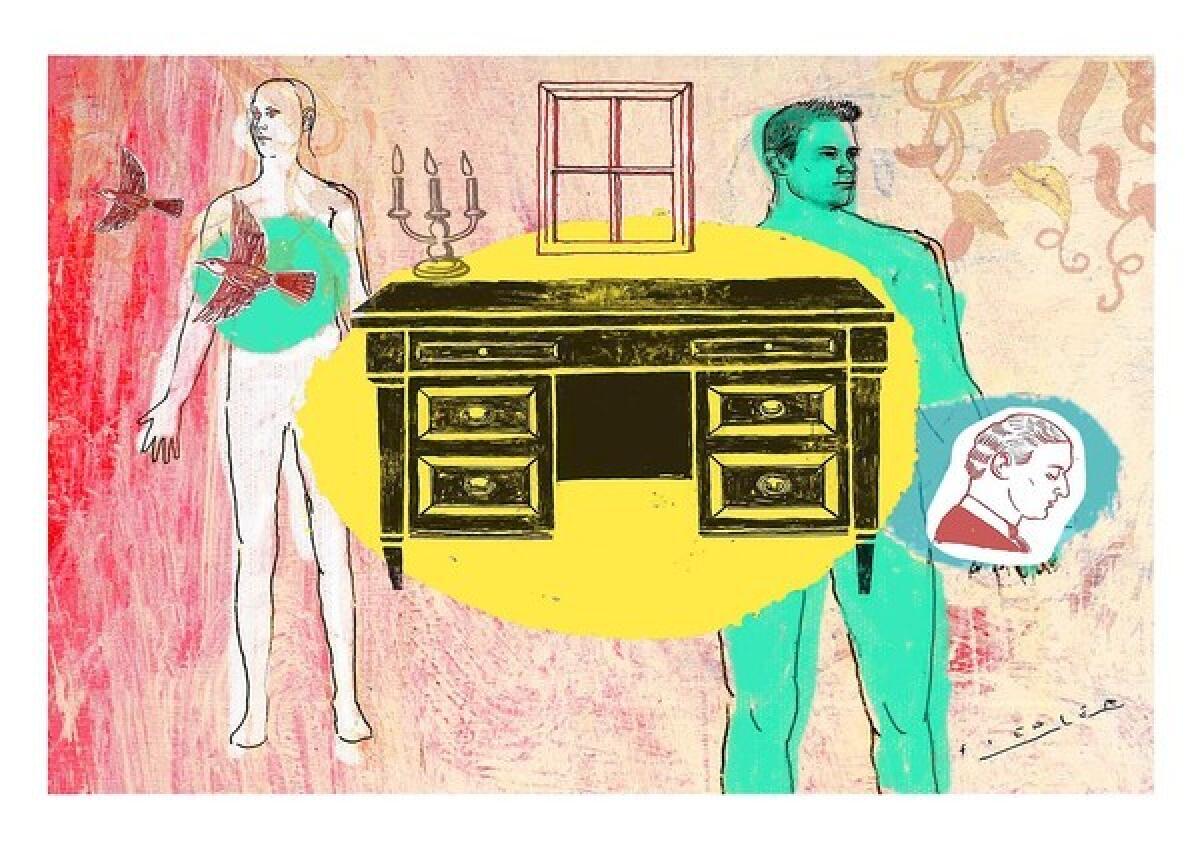

That’s unfortunate, for “Great House” — much like Krauss’exquisite and widely acclaimed “The History of Love” before it — is an exercise in kaleidoscopic storytelling, a novel that seeks to weave four groups of characters into a larger meditation on memory and loss. There is Nadia, a middle-aged novelist transfigured by a youthful interaction with a martyred Chilean poet named Daniel Varsky; for a quarter century, she has written at his desk. Paralleling her experience is Lotte Berg, a generation older and herself the author of elliptical short stories, who also worked at the desk for many years. For Leah and Yoav Weisz, children of an Israeli furniture dealer who specializes in heirlooms pillaged by the Nazis, the desk offers a different reference point, becoming a talisman in both their ongoing struggle with their father and his inability to come to terms with history. Only Aaron — who, after the death of his wife, is brought back in contact with his long-estranged son, Dov — does not have anything to do with the desk.

There’s a lot to be said for using a piece of furniture to evoke the inner life of not just characters but also families — not least because it allows the novel to exist, a bit, outside of time. “Unlike people,” Krauss writes, “… the inanimate doesn’t simply disappear,” and as “Great House” progresses, she establishes the desk as a trace or imago, an echo of the past that reverberates into the present day. And yet, for all the import of this object, it never really sticks to anyone. Nadia may have written all her books while sitting at the desk, but when the time comes, she gives it up without much struggle, “because saying yes felt inevitable.” Lotte parts with it in similar fashion, bestowing it upon the young Varsky because, she explains, “He admired it.”

To be fair, this is part of the narrative momentum of the novel, to shift the desk from one character to another, so it will take on the necessary psychic weight. Still, the ease with which it moves among them only undermines its metaphoric power, reminding us that, whatever it may stir in us, the inanimate remains inanimate, which means, on the most fundamental level, that it can never be enough. During one particularly trying moment, Lotte’s husband reflects on this, thinking about how, in his marriage, “everything … was designed to give a sense of permanence … though in truth it was all just an illusion, just as solid matter is an illusion, just as our bodies are an illusion, pretending to be one thing when really they are millions upon millions of atoms coming and going.” That recognition, that sense of our infinitesimal insignificance, is part of what Krauss is after in this novel, but too often she leaves us with the sense that “Great House” is just a story, in which, as Nadia argues, “the writer should not be cramped by the consequences of her work.”

The exception to all of this is Aaron, who exists as if he were in a different book. Not for him, these illusions about memory or traces: “The dead are dead,” he insists, “if I want to visit them I have my memories.... But even the memories I kept at bay.” Nor does he believe in reconciliation, except of the most unforgiving sort.

For Aaron, life is struggle — with the elements, with his family, with the limitations of the world. “I don’t comfort myself,” he says about his wife, “by imagining that she is sprinkled around me in the atmosphere, or has come back in the form of the crow who arrived in the garden days after her death and stays on, strangely, without its mate. I don’t cheapen her death with little fabrications.” That’s a relentless point of view, hard-nosed nearly to the point of alienation, although alienation too is a position for which Aaron has little use. “Sitting in the garden wrapped in a shawl,” he recalls, thinking of Dov, “… you read books on the alienation of modern man. What does modern man have on the Jews? I demanded, passing you with the garden hose. The Jews have been living in alienation for thousands of years. For modern man it’s a hobby.”

Here we come face to face with the larger theme of Krauss’ novel, to get beneath the surface of contemporary alienation and find our way to a more sustaining truth. That this is impossible, in literature or in life, is part of the point: What redeems the effort is that it is doomed to fail. “No matter how bleak or tragic her stories were,” Krauss writes of Lotte, “their effort, their creation, could only ever be a form of hope, a denial of death or a howl of life in the face of it.” The irony is that, in “Great House,” it is not Lotte, nor Nadia, nor even Leah and Yoav, but only Aaron who brings such an understanding to full-throated life.

david.ulin@latimes.com

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.