Movie review: ‘The King’s Speech’

It takes two, it always takes two.

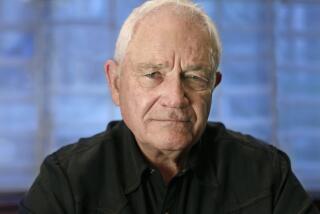

Though romantic couples get the attention, some of the most memorable movie pairings, from Marlon Brando and Rod Steiger in “On the Waterfront” to Geena Davis and Susan Sarandon as “Thelma & Louise,” feature same gender actors playing off each other to breathtaking effect. So it is with Colin Firth and Geoffrey Rush in “The King’s Speech.”

FOR THE RECORD:

“The King’s Speech”: A review of the film “The King’s Speech” in the Nov. 26 Calendar section said that the coronation of Britain’s King George VI occurred in 1936. The coronation was in 1937. —

Simultaneously commoner and king, teacher and pupil, iconoclast and underdog, the meeting of the unstoppable force that is Rush’s speech therapist and the immovable object that is Firth’s future English king is as good as one-on-one acting gets. Both actors completely inhabit their absorbing roles, relishing the opportunity their exchanges provide and adding unlooked-for layers to a complicated human relationship.

Because this British film has the contours of an Oscar-friendly Hollywood story (not for nothing is the Weinstein Co. involved), “The King’s Speech” tends to sound more standard than it plays. In fact, several factors, aside from that acting, keep it involving and well above the norm.

A key aspect is that “The King’s Speech” is based on the true story of the relationship between Lionel Logue, an Australian speech therapist, and Albert, the Duke of York, who was forced to confront his debilitating stammer in the years leading up to his 1936 coronation as King George VI.

Peeks behind the velvet curtain at scenes of royal travail can be involving, witness 1994’s “The Madness of King George,” and this story is exceptionally moving as well. In fact, when screenwriter David Seidler, a boyhood stutterer, approached the Queen Mother, the king’s widow, decades after the fact about a possible film, she wrote back “Please, not during my lifetime. The memory of these events is still too painful.”

Seidler is a veteran screenwriter whose credits include “Tucker: The Man and His Dream” and three Writers Guild nominations for television features. His script is especially good at conveying the push-pull between royal stutterer and plebian therapist, and his words are given extra spirit by fine acting in the other roles.

Playing the matronly but determined Elizabeth, Duchess of York, is Helena Bonham Carter, in tart Merchant-Ivory form and only one of several top British actors that fill out the cast. Especially good are Michael Gambon as Albert’s father, George V, Derek Jacobi as the Archbishop of Canterbury, Jennifer Ehle as Logue’s wife, Myrtle, and in a surprise but very successful bit of casting, Australian Guy Pearce brings surprising life to Albert’s abdicating brother, Edward VIII.

Best known in this country for the multi-Emmy winning “ John Adams” miniseries, director Tom Hooper is a proven storyteller, expert at embracing popular dramatic material without forcing the emotional content. Though little seen over here, features like “The Damned United” and “ Longford” underscore the way Hooper brings intelligence, variety and pace to traditional stories.

Every drama needs a villain, and we catch a glimpse of this film’s antagonist early on: it’s an enormous microphone, looking as sinister as a serial killer. It’s set up at Wembley Stadium at 1925 so Albert, known as Bertie to his friends, can give a speech to be broadcast to the nation and the world.

As played by Firth in top hat and agony, the Duke of York looks like a man headed to his own execution, or at the very least a considerable public humiliation. As the speech heads toward inevitable disaster, Firth beautifully conveys the agony his stutter causes him, as well as his conviction that he is not living up to his royal obligations by not being able to master it.

So as the years roll by the haunted and distraught duke goes off to a series of therapists, a parade of cranks, quacks and well-meaning incompetents who are so disturbing to his personal dignity that he makes his wife swear that she will take him to no more.

The duchess, however, is made of sterner stuff, and she has one more therapist to try. That would be Rush’s Logue, an eccentric, iconoclastic Australian who so insists on having things his own way — “my game, my rules” — that he makes the unbending duke come down to his humble Harley Street office for his appointments.

The keenest pleasure of “The King’s Speech” is watching the developing relationship between two men who initially have a very convincing distaste for each other. When the duke says “you’re peculiar,” Logue says, “I take that as a compliment.” When Logue admits his methods (which involve comically bizarre physical exercise and deft psychological probing) are unorthodox and controversial, the duke allows that those are his least favorite words. When Logue insists on calling him Bertie, the hot-tempered duke wants to call the whole thing off.

What keeps this mismatched couple together is, frankly, the press of world events. When his brother abdicates for “the woman I love,” the duke unexpectedly becomes king, and when World War II begins, his need to effectively address and rally the nation becomes paramount.

The gift of “The King’s Speech” is that it allows us to look on as a pair of masterful actors re-create a monumental test of wills between an imperturbable layman and a king who insists with royal certitude, “I stammer. No one can fix it.” Their dilemma never feels anything less than real, and when they reach the end of their journey together, we share more fully in their emotions and accomplishments than we would have thought possible.

‘The King’s Speech’

MPAA rating: R, for some language

Running time: 1 hour, 58 minutes

Playing Arclight, Hollywood, Landmark West Los Angeles

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.