Robert Hilburn: Michael Jackson: the wounds, the broken heart

I’ll always regret that my last conversation with Michael Jackson ended with him angrily hanging up the phone -- at least I’ve long thought of Michael’s mood that day more than a decade ago as angry. I realize now that a more accurate description would be “wounded.”

Michael was among the sweetest and most talented people I met during 35 years covering pop music for the Los Angeles Times.

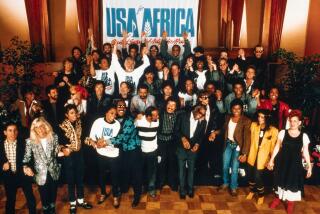

I was fortunate to be present at many of his proudest moments. I was in the audience the night in 1983 that he unveiled the electrifying Moonwalk on the Motown TV special and in the studio in 1985 for the all-star “We Are the World” recording session. I was with him at the Jackson family home in Encino soon after he purchased the Beatles song catalog in 1985.

Michael struck me as one of the most fragile and lonely people I’ve ever met. His heart may have finally stopped beating Thursday afternoon, but it had been broken long ago.

During weekends I spent with him on the road during the Jacksons’ “Victory” tour in 1984, I learned that he was so traumatized by events during his late teens -- notably the rejection by fans who missed the “little” Michael of the Jackson 5 days -- that he relied desperately on fame to protect him from further pain. In the end, that overriding need for celebrity was at the root of his tragedy.

I first met Michael in the early days of the Jackson 5 at the family home in Los Angeles, and the memory that stands out is that Michael, as cute and wide-eyed as an 11-year-old could be, was eager to get through the interview so he could watch cartoons before having to go to bed.

When I caught up with him a decade later, his personality had changed radically. That happy-go-lucky kid was nowhere to be found.

Michael’s sales had fallen off dramatically in the mid-1970s, and by the time he reemerged with the hit “Off the Wall” album in 1979, he was scarred emotionally. There’s often a gap between a performer’s public and private sides, but rarely was it as noticeable as with Michael.

Sitting at the rear of the tour bus after a triumphant concert in St. Louis in 1981, Michael was anxious, frequently bowing his head as he whispered answers to my questions. In contrast to the charismatic, strutting figure on stage, he wrestled with a Bambi-like shyness. Despite the resurgence in his popularity, he complained of feeling alone -- almost abandoned. He was 23.

When I asked why he didn’t live on his own like his brothers, rather than at his parents’ house, he said, “Oh, no, I think I’d die on my own. I’d be so lonely. Even at home, I’m lonely. I sit in my room and sometimes cry. It is so hard to make friends, and there are some things you can’t talk to your parents or family about. I sometimes walk around the neighborhood at night, just hoping to find someone to talk to. But I just end up coming home.”

That’s as far as Michael could go that night to explain his deep-rooted anguish. It would be four more years before he was willing to tell me more.

Michael had signed a book deal with Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis, an editor at Doubleday, before the “Victory” tour, and he wanted me to help him write it. I spent several weekends on the road with him during the tour. I soon discovered that Michael -- who guarded his privacy at all costs -- wanted to put together a picture book, while Onassis wanted a full-scale biography.

After a showdown between the two, Michael’s longtime attorney and friend John Branca called to thank me for my efforts and said Doubleday was going in a different direction. My involvement ended.

During our time together, my conversations with Michael sometimes led -- once the tape recorder was off -- to darker moments from his past. One night when we were going through a stack of old photos, a picture of him in his late teens triggered a sudden openness.

“Ohh, that’s horrible,” he said, recoiling from the picture.

Michael explained that his face was so covered with acne and his nose so large at that time that visitors to the family home in Encino sometimes wouldn’t recognize him. “They would come up, look me straight in the eye and ask if I knew where that ‘cute little Michael’ was.” It was as if the “whole world was saying, ‘How dare you grow up on us.’ ”

Michael said he started looking down at the floor when people approached or would stay in his room when visitors came to the house.

Michael vowed to do whatever it took to make people “love me again.” The rejection fueled his ambition to be the biggest pop star in the world and to try to make his face beautiful. Unfortunately, Michael’s need was so great that no amount of love seemed to be enough.

The stage was his sanctuary. There, he was larger than life and no one could threaten him. Every time he left the stage, he said, he felt vulnerable again.

In the 1981 interview, he told me, “My real goal is to fulfill God’s purpose. I didn’t choose to sing or dance. But that’s my role, and I want to do it better than anybody else. I still remember the first time I sang in kindergarten class. I sang ‘Climb Every Mountain,’ and everyone got so excited.

“It’s beautiful at the shows when people join together. It’s our own little world. For that hour and a half, we try to show there is hope and goodness. It’s only when you step back outside the building that you see all the craziness.”

Michael’s hunger for fame and success struck me as increasingly obsessive and unhealthy.

Even though 1982’s “Thriller” was the biggest-selling album of all time, Michael told me one night that his next album would sell twice as many copies. I thought he was joking, but he had never been more serious.

As years went by, I watched with sadness as his music went from the wonderful self-affirmation and endearing spirit of “Thriller” to something increasingly calculated and soulless. His impact in the marketplace waned accordingly. It appeared that his desperate need for ultra stardom -- the “King of Pop” proclamation -- and his escalating eccentricities made it difficult for audiences to identify with him.

Even some of his “Thriller” fans were ultimately turned off. In the public mind, he went from the “King of Pop” to the “King of Hype.”

When I surveyed leading record industry executives in 1995 to determine pop’s hottest properties, Michael wasn’t in the top 20.

One executive said flatly: “The thing he doesn’t understand is that he’d be better off in the long run if he made a great record that only went to No. 20 than if he hyped another mediocre record to No. 1. The thing he needs is credibility.”

Another executive said simply that Michael was “over.”

Michael was furious when he called me the day after the story ran in The Times.

How could I betray him by writing such lies?

Couldn’t I see the record executives were just jealous?

I tried gently to tell him that I thought there was some truth in what the executives were saying and that he had lost touch with the qualities that once made him so endearing.

“That hurts me, Robert,” he said, his voice quivering.

I felt bad.

I started to say that he could be as big as ever if he would only . . . , but I couldn’t complete the sentence.

Michael hung up.

After that, I followed his life from a distance -- the child molestation charges, the battle with painkillers, the marriage to Lisa Marie Presley, the increasingly bizarre lifestyle.

Although he would periodically announce recording projects or touring plans, I couldn’t imagine, after all the humiliation and disappointment, that Michael could find the strength to step in front of the public again. I thought the fear of failure was too great. It was easier to stay in a fantasy land.

So I was surprised when he announced that he was returning to the stage in a few weeks and was even more surprised when he sold out 50 nights at the O2 Arena in London.

Maybe Michael was stronger than I thought. It took enormous courage to be willing to go back on stage for what could be a make-or-break moment -- and the ticket demand must have given him hope. Despite all that had happened, he saw that he was still loved by millions of fans.

In the best scenario, Michael, 50, would have triumphed in London, not only erasing his mountain of debt but also restoring to himself the sense of invincibility that fame represented. Failure in those shows, however, could have left him even more wounded and vulnerable.

As the July dates neared, I imagined Michael’s anxiety mounting day by day, even hour by hour. There must have been days when he felt he could do it, could reclaim his crown with a series of breathtaking performances and stand forever alongside Elvis Presley and the Beatles in pop music lore.

But what if he was wrong?

What if he wasn’t strong enough, physically and emotionally? What if he couldn’t live up to expectations?

What if no amount of adulation could make him feel safe again?

The stress must have been immense -- and maybe in the end it was too much for his broken heart.

Robert Hilburn was The Times’ pop music critic from 1970 to 2005. Parts of this article are excerpted from his memoir, “Corn Flakes With John Lennon, and Other Tales From a Rock ‘n’ Roll Life,” which will be published in October.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.