Critic’s Notebook: An American’s take on ‘Downton Abbey’

When, during his recent State of the Union address, President Obama spoke of “an economy where everyone gets a fair shot, everyone does their fair share, and everyone plays by the same rules,” I wasn’t worried about the GOP response or changes to our tax codes. I was worried about Downton.

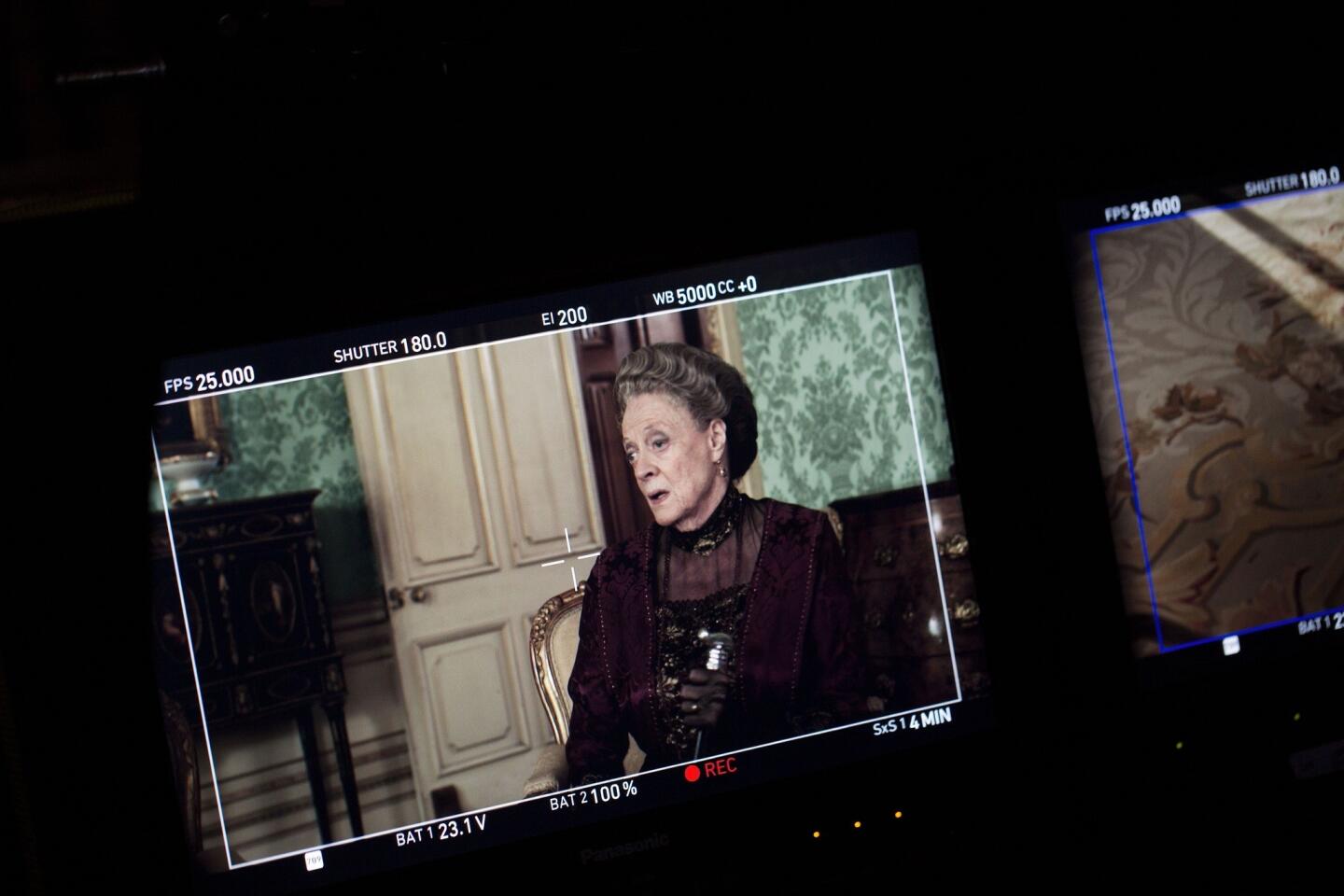

Everyone loves “Downton Abbey.”PBS’ biggest hit in years, it’s won Emmys, a Golden Globe and the critics’ hearts. We are all smitten with the elegant writing, the fabulous cast (Maggie Smith! Weekly!), the marvelous setting and the chance to wallow in the social mores and accouterments of another age.

Even with its high-lather soap factor, no one would consider “Downton Abbey” a guilty pleasure — it’s “Masterpiece,” for heaven’s sake, the television equivalent of graduate school — though certainly creator Julian Fellowes makes it easy for an American audience to empathize with pampered members of the master class. So easy that one wonders why conservative Republicans would want to cut funding for PBS when it’s delivering such a soothing message about the benevolent rich.

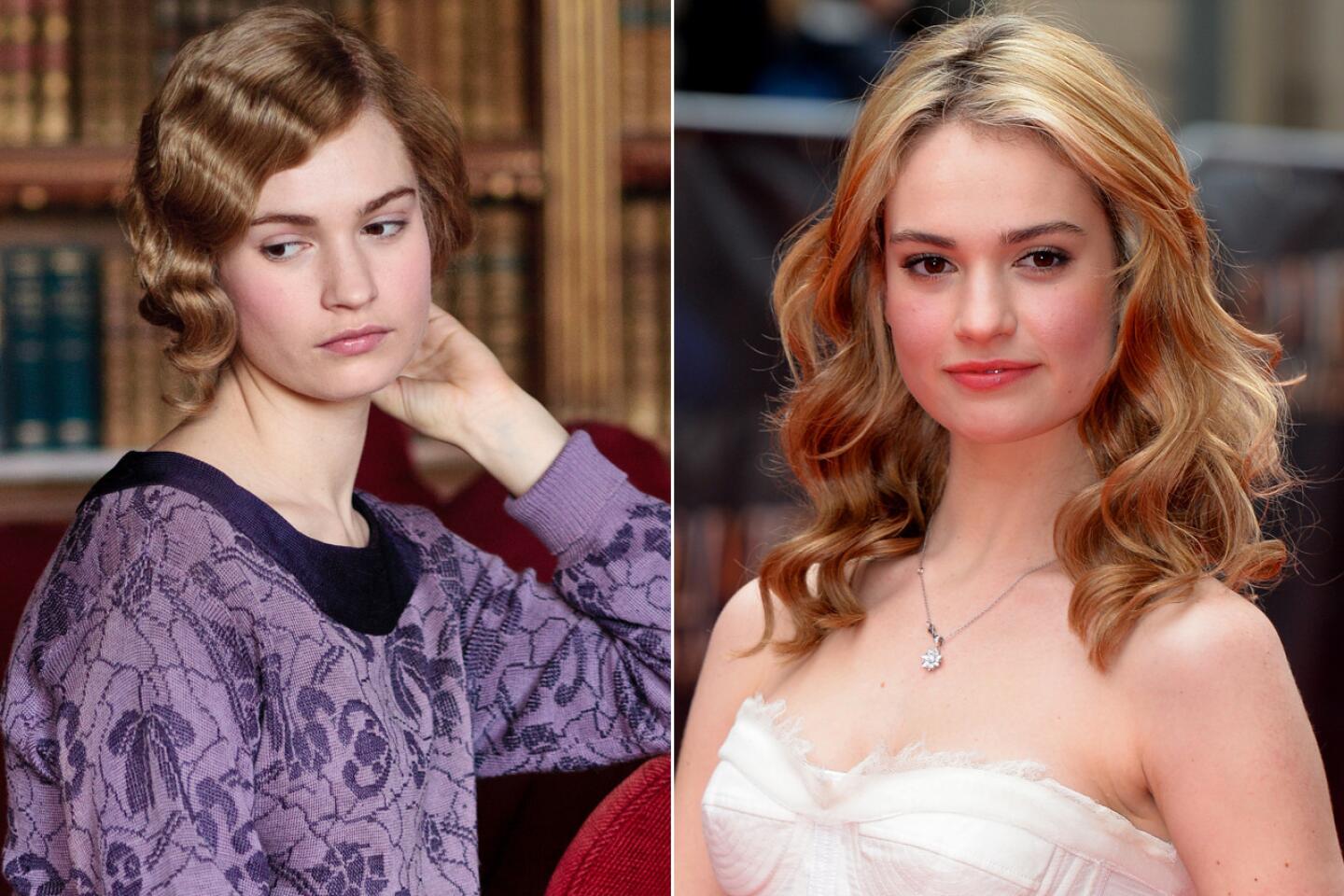

VIDEO: Interviews with the women of ‘Downton Abbey’

By conveniently blurring the class distinctions of the time with a lot of noblesse oblige and more than a dash of modern psychology, Fellowes and his writers allow their audience the benefits of a romantic period piece and none of the troubling drawbacks. The absence of race as a major issue may provide the American audience an instant comfort zone — Americans love to pretend that we, unlike our mother country, are an egalitarian and socially mobile society — but “Downton Abbey” is, after all, a British version of “The Help,” the tale of an oppressive social and economic system that is finally being called into question.

Yet the tone of the two works could not be more different; in “The Help,” the moneyed elite are portrayed as catty women devoid of human decency. In “Downton Abbey,” decency does not even begin to describe it. In “The Help,” the audience is justifiably outraged by what is clearly an untenable situation. In “Downton Abbey,” well, yes, one supposes even a scullery maid deserves an education and the hope of life outside servitude, but mightn’t we consider what will be lost as well? A more gracious way of life, a time when at least one knew where one stood?

Eulogies for a more stately past are invariably expressed by members of the ruling class, while behind them the teeming multitudes empty the chamber pots, chew on gristle and die in childbirth. But not at Downton. Oh, good gracious, no.

At Downton, the servants are part of the family; it says so right on the website. Certainly, they address their employers with a familiarity that would leave even literature’s most beloved servants — P.G. Wodehouse’s Jeeves, say, or Dorothy L. Sayers’ Bunter — gasping in horror. Not to mention unemployed.

But then, “Downton Abbey” is a modern television show, and modern audiences can no longer sympathize with anyone in the master or even “Mister” role. Atticus Finch may be the last American hero to get away with it; even Frodo and Sam’s employer-servant relationship was almost entirely obscured by their friendship in the film version of “The Lord of the Rings.”

Indeed, from the moment we met Robert Crawley, Earl of Grantham (Hugh Bonneville), last season, it was clear that Fellowes would not be wielding the stinging class satire of his own “Gosford Park” or even the strictly upheld divisions of “Upstairs Downstairs.” The lordship had just learned the fate of his heirs aboard the Titanic, and his first thought was for the poor souls in steerage. And when discussing the future of Downton, he is not so much worried about his own status as he is wracked with concern for his servants — if this last remnant of the system should fail, where would they find jobs?

PHOTOS: Maggie Smith through the years

The first season of “Downton Abbey” put class very much front and center. When it became clear that the new heir was a young lawyer named Matthew Crawley (Dan Stevens), all manner of snobbery was exposed for the amusement of the modern audience. Led by Robert’s mother, the straight-backed and sharp-tongued dowager countess (Smith), stands were made against this mingling of castes, with the eldest daughter, Lady Mary (Michelle Dockery), physically unable to disguise her disgust at the thought of marrying a working man, even to preserve her beloved Downton. Yes, her father entered a similarly financial-based arrangement with an American heiress, but Cora, Countess of Grantham (Elizabeth McGovern), is now so passionately and universally loved that one wonders what on earth those malcontents Edith Wharton and Henry James were yammering about when they wrote their scathing portrayals of similar matrimonial schemes.

Matthew and his mother, Isobel (Penelope Wilton), were also somewhat repulsed by the archaic class system, though Matthew, softened by his inexplicable love for Lady Mary, eventually accepted that being a lord was more responsibility than privilege. (All that job creation and what not.) Isobel, however, remains unmoved and in the second season has been increasingly portrayed as one of those tiresome women who think the rich should always be “doing something.”

The other class division, that of upstairs and down, was — and continues to be — glossed over with a patina of sentiment. In the first season, one maid seeks economic independence by learning to type in hopes of becoming a secretary, but only three characters express angry dissatisfaction with the yawning chasm between upper and lower. Tom (Allen Leech), the socialist chauffeur, is the most promising, but by Season 2, he is more consumed with his love for Lady Sybil (Jessica Brown-Findlay) than he is with political fervor.

Meanwhile, the bitter lady’s maid O’Brien (Siobhan Finneran) and her scheming (and homosexual!) protégé, the footman Thomas (Rob James-Collier), are clearly villainous. (For one thing, they’re the only ones who smoke, often in a way that can only be described as furtively.) Even more so in the second season, when Downton becomes an infirmary for officers during World War I and Thomas is put in charge.

And upstairs, everyone has found a new common foe — the boorish and bullying Sir Richard Carlisle (Iain Glen), a newspaper editor (so, obviously, Satan in a dinner jacket) who vows to keep a family scandal at bay, but only if Lady Mary will marry him

Fellowes dutifully addresses the shifting social landscape both during and after the war, but our sympathy is always with the gentry. We root for Lady Sybil to marry Tom but exchange outraged glances with the current and dowager countesses of Grantham whenever Isobel suggests that Downton be more than a private residence and bare our teeth when Sir Richard tries to buy the things that one should simply inherit.

Most important, we want Lady Mary to be happy.

Why, I cannot tell you. Dockery is a lovely woman who gives a fine and nuanced performance, and Lady Mary does have an endearing capacity for frankness. But in another, more progressive time, it would be the scullery maid Daisy (Sophie McShera) or even the poor, angry, gay Thomas who would emerge as the true hero of “Downton Abbey,” a character embodying the struggles of a brave, new society in which one’s ambition and ability mean more than one’s lineage.

Instead, it is Lady Mary who commands Fellowes’ heart and the show’s center stage. Downton has worked its magic, and even the most left-leaning among us find ourselves hoping for its preservation, and Lady Mary is key. If she and Matthew don’t marry, who knows what will happen?

Never mind that this empire runs on the blood, sweat and tears of an underclass purposefully denied education, upper-ward mobility or any protection save the arbitrary generosity of its employers. Should Downton fail, a bit of brightness will fall from the air.

Exquisitely rendered and perfectly displayed, “Downton Abbey” is a beggar’s banquet and, while Occupiers protest and the politicians argue, while the international economies shiver and the gap between rich and poor grows too wide to be breached by any staircase, we eat it up with a silver spoon.

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.