Review: Director Jennifer Fox has turned the pain and confusion of childhood sexual abuse into ‘The Tale’

“The Tale,” which premieres Saturday on HBO, begins with a disclaimer: “The following movie is based on filmmaker Jennifer Fox’s personal experience. It contains material of a sensitive nature. Viewer discretion is advised.”

Advised viewer discretion is one of those warnings adults tend not to hear, as something meant for someone other than themselves. Still, before you watch, you may want to seriously consider whether “The Tale” is for you. It’s a very fine film, powerful yet nuanced and not in any sense sensational or exploitative, but its subject matter is the sexual abuse — the seduction — of a child, and it is a story told from the inside.

It is not explicit, but it isn’t discreet. Fox doesn’t stay modestly out of the room when bad things are happening.

“The story you are about to see is true,” says adult Jennifer (Laura Dern) as the film begins, “as far as I know,” with an emphasis on “I.” (Fox keeps her own name, but other “identifiable details” have been altered.) Heretofore a maker of documentaries (“Beirut: The Last Home Movie,” “My Reincarnation”), in “The Tale” — “based on ‘The Tale,’ by Jenny Fox, Age 13,” a closing credit tells us — Fox here fictionally recounts coming to terms with her sexual abuse by a track coach, Bill (Jason Ritter), attached to “Mrs. G” (Elizabeth Debicki), a champion horsewoman who ran a small riding camp that Jenny attended.

Jennifer has a strong sense of self, bordering on stubbornness, even if she is not always correct in her self-assessment; she’s living with the effects of her childhood abuse without making the connections or even defining the abuse as abuse. She has somehow normalized the relationship in her mind, describing Bill as her “first boyfriend” and “older,” without putting a number on it. Pressed, she offers, “It was the ‘70s” as conversation-ending explanation. (It’s a phrase we’ll hear again — there are a lot of internal rhymes in Fox’s screenplay.)

“I’ve met two very special people I’ve come to love dearly,” Jenny’s composition begins. “Imagine a woman who’s married and a man who is divorced sharing their lives in close friendship, loving each other with all their souls yet not being close with their bodies. Get this. I’m part of them both.”

What changes things is a call from Jennifer’s mother (Ellen Burstyn), who has run across an old middle-school composition — the eponymous “The Tale,” which Jenny had represented to her teacher as fiction — and realizes that it is, in fact, a true story. Jennifer defends her history; the first flashback scenes, echoing Jennifer’s imperfect memory, portray her as older and more mature than she was at the time. (Jessica Sarah Flaum first plays Jenny at 15.)

But when her mother corrects her, and shows Jennifer a picture of her 13-year-old self — “I was so little,” Jennifer says — the flashbacks begin again. Isabelle Nélisse takes over the role, and every meaning alters. (It is disturbing too how much difference those two years make, to the viewer as well as to Jennifer — but we are strangely accustomed to movies and television shows in which high school sophomores live lives of sexual abandon.)

The film knits together past and present, with passages from Jenny’s “The Tale,” and “new interviews” in which an off-camera Jennifer interrogates figures from her past, as if in a documentary — including her uncooperative younger self. (“It’s my life, mine,” Jenny tells Jennifer, stomping off. “Let me live.”) Such theatrical devices are nothing new, and the multiple shifts and meetings between timelines could easily seem clichéd or contrived if not for the smooth, almost dispassionate way Fox handles them. That is, she allows her characters their passions without loading on extraneous indicators of shock or approval or sadness.

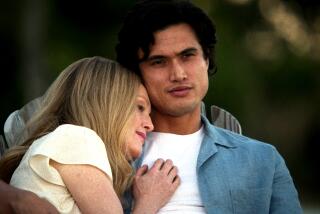

Much depends on the acting of course, and the performances — including Common as Jennifer’s supportive but stonewalled partner and John Heard as older Bill — are splendid throughout. Dern is typically good, disintegrating and reintegrating without making too much a show of it, and as the very different older women in Jennifer’s life, Conroy and Burstyn are each quietly superb, and just good to see on-screen. Young Nélisse carries an enormous weight with astonishing poise. (The closing credits assert an adult body double was used for some shots, and Fox has said that Ritter and Nélisse’s intimate scenes were edited together from separate takes, out of one another’s presence.)

Ritter has the hardest job here, needing to appear interesting and attractive to Jenny even as, for the viewer, every second spent in his company is difficult at best and at times excruciating. Agreeable and opaque and undoubtedly cast for the nice-guy aura he inherited from his father, John Ritter, he does as well with it as anyone could.

Were the film entirely a work of fiction, it would still be an impressive, cohesive piece. A tight script is never far from addressing its themes without ever hectoring the viewer; “The Tale” is always a drama and never a tract. And yet that it is based in fact does matter, not just for the authenticity “true story” adds, but because ideas about fiction and non-fiction, truth and lies and the editing of scraps of information — what a documentarian does, after all — are actively addressed.

“We tell ourselves stories in order to live,” Jennifer tells a class in documentary filmmaking, quoting Joan Didion and describing herself.

ALSO

Jennifer Fox’s drama ‘The Tale’ brings #MeToo to Sundance

Sunday Conversation: Laura Dern on fame, feminism and subversive roles

From the Archives: A Look at Vanishing Aristocracy in ‘Beirut: The Last Home Movie’

Follow Robert Lloyd on Twitter @LATimesTVLloyd

More to Read

The complete guide to home viewing

Get Screen Gab for everything about the TV shows and streaming movies everyone’s talking about.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.