“Collision 2012’ and ‘The Gamble’: Insight on the election as it truly was

The intense competition of a presidential campaign almost always generates innovation, from the first television ads for Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1952 to Bill Clinton’s rapid-response war room in 1992 to George W. Bush’s get-out-the-vote drive in 2004. In 2012, the cutting edge involved data.

The way the Obama campaign exploited vast amounts of information to guide which doors it knocked on, what voters it targeted and what ads it bought already has entered into election lore.

But data also significantly changed the journalism of the 2012 campaign. Number-savvy reporters who know how to use statistics to tell a story, typified by Nate Silver and his 538 blog, took what had been a sidelight of political coverage and made it a main act. Their work exposed the shallowness and inaccuracy of a large chunk of traditional media commentary, the talk of “momentum” and “game changers” and the over-reliance on self-serving accounts by campaign strategists.

That new approach created significant tension between camps of political analysts, pitting numbers against narrative. But the two need not conflict. Indeed, when done well, the approaches complement each other, as demonstrated by new books from one of America’s best political journalists and two rising stars in political science.

On the narrative side, no one does better than Dan Balz, senior political writer for the Washington Post. His fourth and latest book, “Collision 2012: Obama vs. Romney and the Future of Elections in America,” provides the best account of the campaign seen from inside — the personalities, egos and political calculations of the race. For those seeking a concise, fair and deeply reported account of campaign 2012, this is the book.

Lynn Vavreck of UCLA and John Sides of George Washington University come at the same story from a different angle in “The Gamble: Choice and Chance in the 2012 Presidential Election.” Where Balz paints pictures of the contending armies and their generals, Sides and Vavreck offer a detailed, quantified description of the battlefield — an effort to provide political science insight in real time.

The accounts — one thoughtfully journalistic, the other accessibly academic — agree on the big picture of the race, and both puncture some of the conventional wisdom that dominated coverage, particularly on television, during the campaign year.

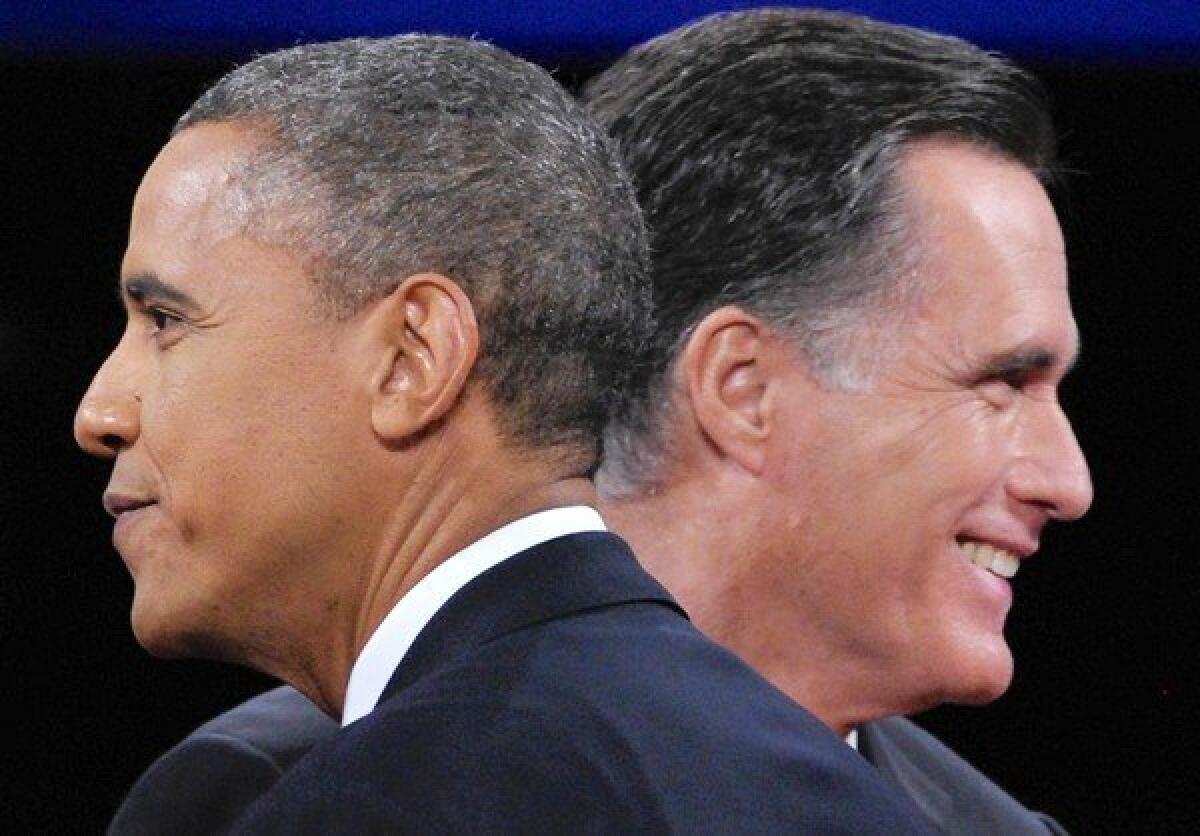

In their accounts of the Republican primaries, for example, neither accepts the idea of a deeply divided party searching desperately for “anyone but Romney.” Instead, as Vavreck and Sides show, polling data make clear that Romney was at least broadly acceptable to the majority of Republican primary voters from the outset. Balz concurs while also describing how Romney’s well-planned and heavily provisioned campaign took great care to ensure that no strong rival would emerge.

But because the works come at the subject from disparate points of view, they offer different insights.

In explaining the GOP primary campaign, for example, Sides and Vavreck describe the cycle of “discovery, scrutiny and decline” that each of Romney’s rivals endured. They examine the pattern as largely a phenomenon of media coverage: An event such as a debate triggers an upsurge in coverage of a previously little-known candidate. Greater coverage, in turn, leads to a rise in the candidate’s name recognition and standing in polls. Higher standing in the polls triggers more scrutiny, which typically, then, causes the candidate’s fortunes to decline. The strength of their account is to properly focus attention on the media as a player in the process rather than as a detached referee.

An intense focus on the numbers, however, can make the process appear bloodless or mechanistic. Balz’s account fills in a missing element — the unpredictability of individuals, the personal quirks that caused highly touted hopefuls like former Minnesota Gov. Tim Pawlenty or Texas Gov. Rick Perry to flame out as candidates.

Indeed, the book’s highlight involves such personal factors: New Jersey Gov. Chris Christie’s detailed, self-serving but also indiscreet account of how Republican notables, including Henry Kissinger, Nancy Reagan and some of the nation’s wealthiest businessmen, tried to woo him into the race.

At the peak of the courtship, in September 2011, Christie delivered a speech at the Reagan Library in Simi Valley. He describes the scene to Balz this way:

Mrs. Reagan “came in and sat down next to me and she said, ‘you know, this is the fastest sellout we’ve had in the history of these talks at the museum.’”

“I said, ‘No, I wasn’t aware of that, Mrs. Reagan.’”

“She says, ‘Hmmm, that says something, doesn’t it, Governor.”

A few minutes later, “she turned to me and she said, ‘Do you see that podium?’ I said, ‘Yes.’ She goes, ‘That was one of Ronnie’s podiums from the White House.’”

“I sat there for a second and I just turned to her and I said, ‘You’re bad, you know that?’ She had this big smile on her face. She knew exactly what she was doing.”

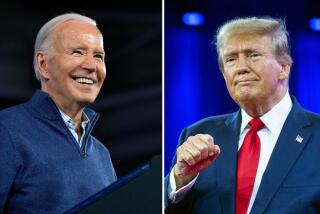

Would Christie have done any better against Obama than Romney did? There is, of course, no way to know. But both Balz’s reporting and the political science analysis stress a key point that, again, contradicts widespread conventional wisdom: Obama started the race as the favorite and retained that position all along. The 2012 campaign was never a race a Republican would easily win.

Balz explains the very different assumptions with which the campaigns approached the race. Romney’s strategists were “virtually certain that the campaign would turn on the economy and voters’ dissatisfaction with the president’s performance.” Obama’s camp believed that voters saw the country’s economic troubles as part of a long-term decline of the middle class and that Romney’s background made him uniquely ill-suited to address their concerns.

The result would seem to bear out the Democratic view, but as both books make clear, there’s scant evidence that a different sort of Republican campaign would have led to a different outcome.

As Vavreck and Sides say, there were no “game changers” in the 2012 campaign but instead a lot of “game samers.” The country began the election season divided between partisan camps and ended it that way. The economy grew slowly but fast enough to make the incumbent the favorite. The rare moments of drama — the videotape of Romney disparaging 47% of the population as “takers,” Obama’s listless performance at the first debate — actually moved relatively few voters and largely canceled each other out.

For both sides, the campaign was largely an effort to mobilize core supporters and get them out to vote. For candidates in a partisan era, that’s the surest route to victory, and Obama’s success at targeting voters will no doubt become the template for both parties. But, as Balz notes, that victory comes with a price that becomes more apparent with each passing month.

“The techniques used to motivate left and right are not ones designed ultimately to bring the country or the parties together once the election is over,” he writes. Both candidates “operated within comfortable boundaries at a time of intractable problems.”

Lauter is The Times’ Washington bureau chief.

Collision 2012

Obama vs. Romney and the Future of Elections in America

Dan Balz

Viking: 400 pp., $32.95

The Gamble

Choice and Chance in the 2012 Presidential Election

John Sides and Lynn Vavreck

Princeton University Press: 352 pp., $29.95

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.