Michael Connelly’s ‘The Black Box’ harks to ’92 L.A. riots

- Share via

The Black Box

By Michael Connelly

Little, Brown: 400 pp.; $27.99

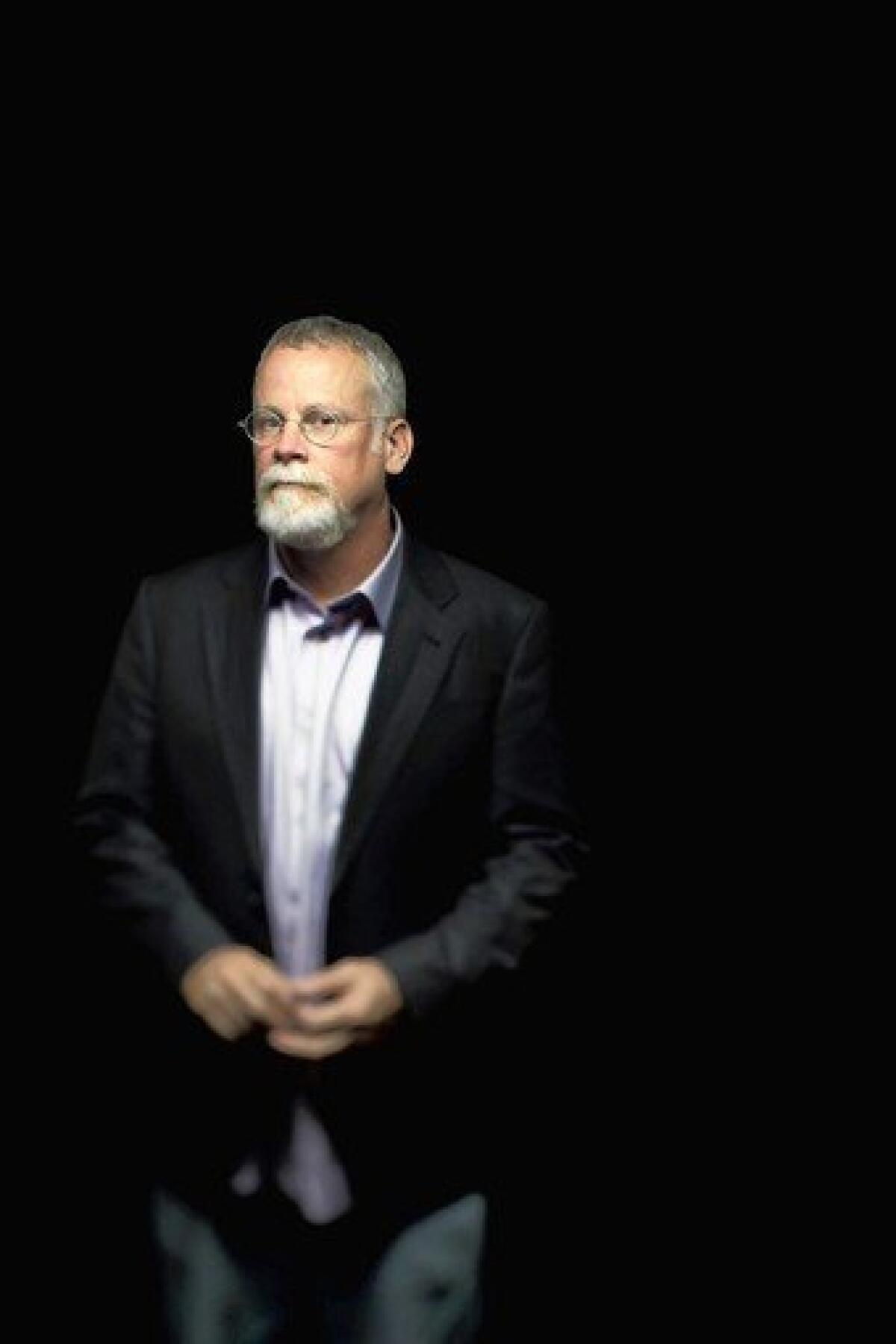

Few crime writers are as prolific or as successful as Michael Connelly. A former Los Angeles Times reporter, Connelly has penned 25 novels over the past two decades, which have sold more than 40 million copies and garnered major crime writing awards in the U.S., France and Italy. And while he has made notable forays into stand-alone and serial thrillers, Connelly’s fictional universe centers on Hieronymus “Harry” Bosch, who made a memorable debut 20 years ago in 1992’s Edgar-award winning “The Black Echo” as a former Los Angeles Police Department Robbery-Homicide Division detective exiled to investigating murders for the department’s Hollywood Division.

Emotionally wounded in those early years and principled throughout his career, Bosch is driven to solve crimes by a personal and professional code of ethics that dictates “everybody counts or nobody counts,” and that guides his actions as surely as the North Star.

Longtime fans of the series have followed Bosch’s career progression from solving Hollywood homicides — and navigating numerous run-ins with various LAPD top brass — through early retirement and a return to the LAPD and the Robbery-Homicide Division’s Open-Unsolved Unit under a deferred retirement option plan that allows retirees to return as contract employees for up to five years. With only a few years left on Bosch’s extended contract and a rapidly maturing teenage daughter eager to take up Harry’s crime-fighting mantle, there is a palpable sense of time passing in “The Black Box,” the 18th novel in the series.

The ticking clock is reinforced by a flashback early in the novel to the 1992 murder of Anneke Jespersen, a young Danish photojournalist, during the Rodney King riots. Jespersen’s body was found by a National Guardsman in an alley near the infamous corner of Florence and Normandie, a scene so chaotic that Bosch could spend only a few minutes gathering what scant evidence there was before he and his then-partner were hustled by guardsmen to the next victim.

Fast-forward to 2012: Marty Maycock, the current LAPD police chief, mindful of the media potential of the 20th anniversary of the riots, orders a “fresh look at all unsolved murders that occurred during the unrest in 1992.”

Bosch, one of the more seasoned detectives in the Open-Unsolved unit, requests the Jespersen case, fully aware that it presents daunting challenges, not the least of which is only one piece of hard evidence — a shell casing from a 9-millimeter handgun that Bosch scooped up that night 20 years ago. But Bosch’s never-failing zeal for avenging his victims’ murders and his sense of guilt for having abandoned Jespersen provide the spark to get him started — plus his belief that every case had a black box, “[a] piece of evidence, a person, a positioning of facts that brought a certain understanding and helped explain what happened and why.”

Connelly has always excelled at building suspense while paying careful attention to police procedural detail. Notable in “The Black Box” are how the procedural tools of the past — the Thomas Bros. maps and “shake cards” a veteran detective kept on ‘90s gang members handed over to Bosch in a black box — are combined with the databases and firearm forensic technology that allow Bosch and his computer-savvy young partner, David Chu, to connect the casing to a gun used in Jespersen’s murder and those of several others in the neighborhood over a 17-year period.

But just as the “gun walk” yields evidence that could kick the case up to a more active level of investigation, a countervailing, corrosive element comes into play — Chief Maycock’s worries that if “the only riot killing we clear during the twentieth anniversary is the white girl murdered by some gangbanger,” violence could reignite in the city.

Despite Maycock’s self-serving directive to slow the pace of his investigation and quietly clear the Jespersen case later, away from the anniversary publicity, Bosch is undeterred. Not even a suspiciously timed inquiry into his conduct during the investigation by Detective Nancy Mendenhall of the LAPD’s Professional Standards Bureau — an inquiry that could lead to cancellation of Bosch’s contract — can stop him from following the trail from Los Angeles north to Stanislaus County. Along the way, Bosch makes connections that yield enough surprises and suspense to keep readers engaged, even if the chronology of events leading up to Jespersen’s murder or details of L.A. and the 1992 riots give rise to some nagging questions.

Yet what lingers in the mind after reading “The Black Box” are the more complex moral dilemmas that arise for Bosch, which he has faced countless times throughout his career. How Harry Bosch resolves them, here as in last year’s “The Drop,” suggest a way of finding light in the darkness that will tantalize fans of the series as they realize that Bosch’s mission of fighting crime may be passed on, as advancing age and circumstances force Connelly’s iconic detective to yield the stage, to a younger generation of crimefighters waiting in the wings.

Book critic and crime fiction writer Paula Woods’ Charlotte Justice series, including “Inner City Blues,” is set in the years during and after the 1992 Rodney King riots.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.