Family curse

TETSUO MIURA’s “Shame in the Blood” (1961) has sold more than a million copies in Japan. After reading Andrew Driver’s translation, Miura’s first into English, I can’t think why. Though fluidly told, this novel -- really a collection of autobiographical stories, most of them scrutinizing from a different angle the travails of an aimless, bitter young man (Miura, according to his publisher, “pursued writing as a way to purify his ‘cursed blood’ ”) -- lacks narrative momentum, its chapters petering out with little force.

The unnamed narrator, a university student in Tokyo, is consumed by his siblings’ tragedies and betrayals. His older sisters both committed suicide; his eldest brother vanished; another brother ran off with the family fortune. Only his parents and youngest sister (purblind, thus unmarriageable) remain. He offers a bleak explanation for the family woes: “My suspicion was that the very blood that linked us all could itself be tainted. And the most frightening thing was the inevitable reality that the tainted blood of my siblings also ran through my own veins.”

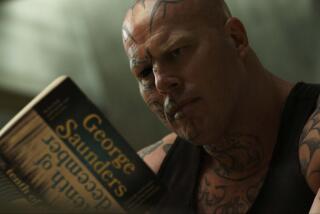

While dining one night with his classmates, the narrator meets a waitress named Shino, whom he befriends. When he learns she has agreed, largely against her will, to marry another man, he demands she break the engagement. She does, timidly, and they begin their life together. In their shabby apartment, Shino assembles ice-cream cartons for a living. The narrator, writing stories that don’t sell and forced to pawn his books to make ends meet, succumbs to despair (“I was like a mule . . . pulled along by an invisible rope. Perhaps I was being pulled to the slaughterhouse”). He daydreams at his desk about his lost hopes.

Little else happens. The deaths of Shino’s and the narrator’s fathers are described in detail but have little emotional import for the narrator, who, at his father’s deathbed, ponders the supernatural: “I was poised, ready to capture with my various senses any event, however small, that might occur above his body in the next few moments.” Impecunious, he eventually returns with Shino to his mother’s country house. Then comes a flashback to his youth. Although providing a palpable sense of his bewilderment at the suicides and desertions of his siblings, it seems awkwardly placed; after all, the reader has already seen him unravel.

The book’s last chapter features another nameless narrator, who, though financially solvent, alternates between a familiar anomie and rage at his wife, whom he regularly abuses, physically and verbally, after he finds out she was raped before they met. She unexpectedly becomes pregnant, and while he is visiting her in the hospital, she asks him to help her with her bedpan. As he listens to her urinate (“a clear, sweet sound, like the ringing of a little bell”), he thinks about making a fresh start. “But that was an impossible wish. Even the sound of the little bell had become nothing but a yellow, frothy sound. We would have to make our fresh start from the here and now, as many times as it took.”

Thus concludes “Shame in the Blood,” on an ambiguously hopeful note that’s rare in a book as meandering as its characters.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.