Discoveries

Small Memories

A Memoir

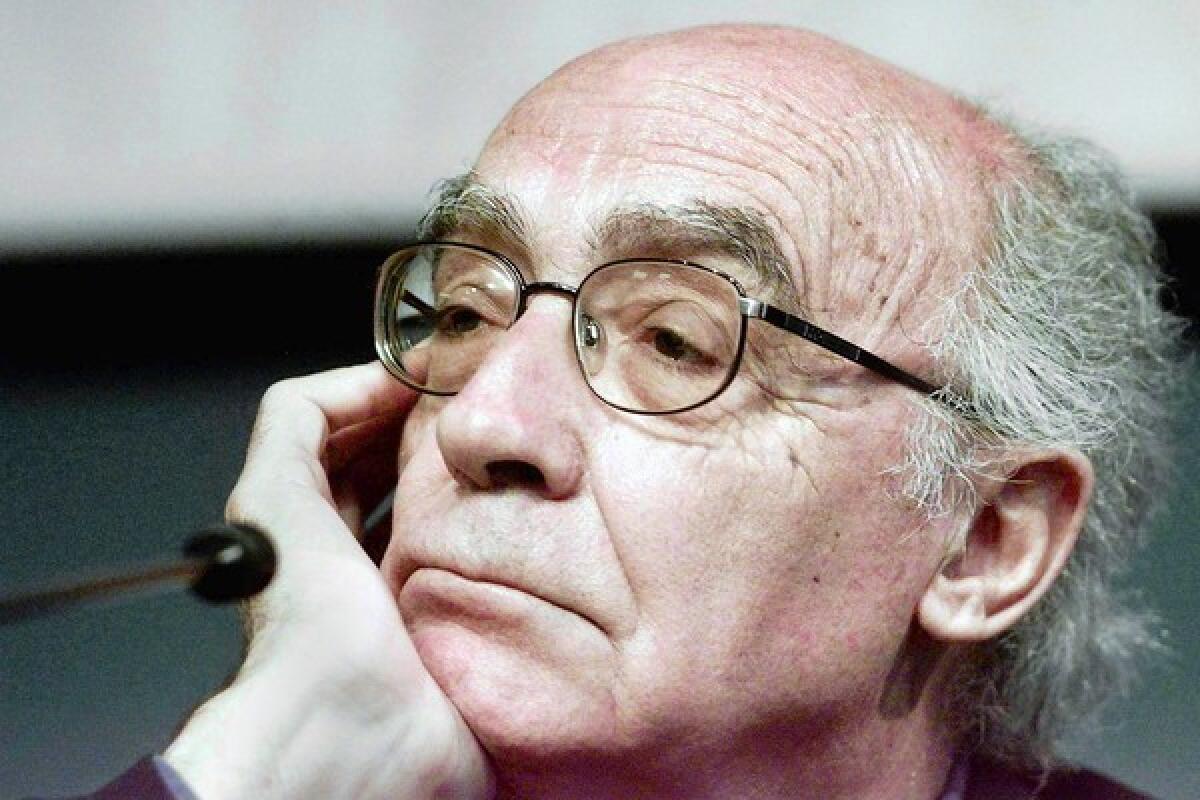

José Saramago, translated from the Portuguese by Margaret Jull Costa

Houghton Mifflin Harcourt: 159 pp., $22

“Sometimes I wonder if certain memories are really mine or if they’re just someone else’s memories of episodes in which I was merely an unwitting actor and which I found out about later when they were told to me by others.” Who hasn’t felt this way? Wondered whether a memory came from a photograph or a story or an actual event?

José Saramago, driven by longing for the village in which he was born but also for a self he fears he has lost, goes painstakingly back over his early memories. Sometimes he writes in the third person, sometimes the first. Some events are more vivid than others — pinned in the consciousness of his long life by pain or beauty or the intensity of the senses. Olive trees and cornfields, the cruelty of bullies, skinned knees, various courtships, learning to read, the death of his 4-year-old brother when he was 2 — Saramago climbs these and other mountains in search of a view. “If only I could once again plunge my childhood nakedness into the river, if I could grasp in today’s hands the long, damp pole or the sonorous oars of yesteryear, and propel across the water’s smooth skin the rustic boat that used to carry, to the very frontiers of dreams, the being I was then and whom I left stranded somewhere in time.” The writer died last year at age 87.

The Enchanter

Nabokov and Happiness

Lila Azam Zanganeh

W.W. Norton: 228 pp., $23.95

Reading was difficult for Lila Azam Zanganeh, until she found Nabokov. Through Nabokov she learned the art of happiness and the art of reading and the art of ecstasy. “We read to reenchant the world… Deciphering, trudging into unknown regions, making one’s way through an intricate atlas of sentences, startling darkness, unfamiliar flora and fauna.” In this adventuring spirit, the author leads us through the work and life of her favorite author, who died when she was just 10 months old. It is a contagion of happiness, a landscape of luminous discovery. Facts, words, characters, style, invention — she writes in flashes, like a camera lens opening and closing. Here’s Nabokov in pursuit of butterflies; Nabokov on the Swiss Riviera; Nabokov playing tennis on a “tawny court” surrounded by pine trees in a Russian summer in 1910. Like the character in Nabokov’s novel “The Gift,” Azam Zanganeh, crafts a practical handbook in one section: “How to Be Happy.” She looks at various kinds of happiness found in Nabokov’s work: unnatural and natural happiness, particles of happiness, happiness through the looking glass, the use of words to create happiness (the reader swallows them one at a time); words such as “cochlea,” “conolorous,” “gloaming” and “fritillary.”

At times, one feels helpless and transported, led by the hand (two hands —Azam Zanganeh’s and Nabokov’s) to a very strange and glittering place.

A photograph of Nabokov closing in on a butterfly with a net the size of a full moon says it all.

Selected Poems

Robert Pinsky

Farrar Straus Giroux: 210 pp., $26

For 36 years, Robert Pinsky has been writing his exciting, musical poetry: “Air an instrument of the tongue,/ The tongue an instrument/ Of the body, the body/ An instrument of spirit,/ The spirit a being of the air.” And it’s true, his poems bubble up and dissolve like fireworks, like something written across a stretch of blue sky, seen from the warm sand. “What is Imagination,” he asks in “Ode to Meaning,” “But your lost child born to give birth to you?” This is one exuberant collection. Baseball, desire, jazz — only poetry could hold them all.

Salter Reynolds is a Los Angeles writer.

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.