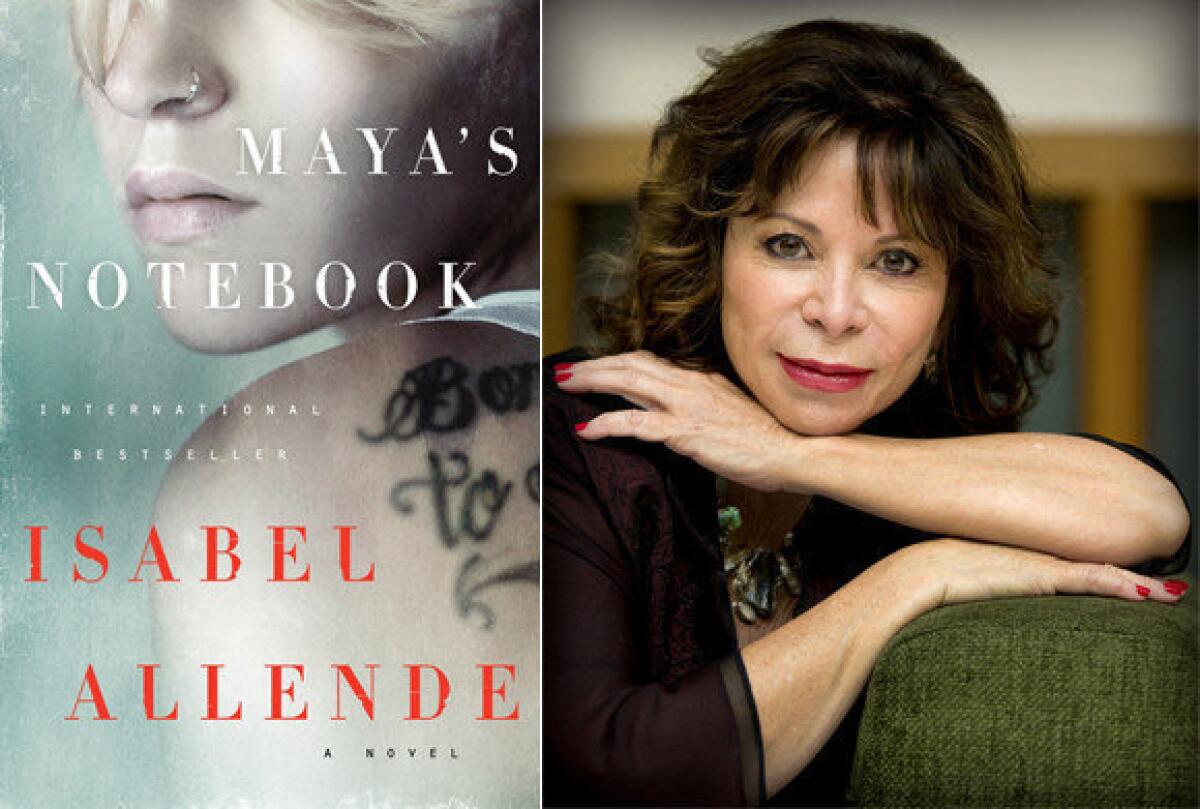

A teen’s quest for self-discovery in ‘Maya’s Notebook’

Whatever happened to magic realism?

The question arises when dipping into “Maya’s Notebook,” Isabel Allende’s bruising, cinematically vivid new novel. It’s an exercise in gritty realism rather than the fanciful folkloricism that Allende has been known for, accurately or not, since her fictional debut, “The House of the Spirits,” 30 years ago.

Magic realism always was more of a publishers’ marketing coinage than an apt description of the works of the so-called Latin American Boom, which looms over Spanish-language literature like Easter Island monoliths: Mario Vargas Llosa, Julio Cortázar, Carlos Fuentes and Gabriel García Márquez. In fact, the magic realist tag applied only to a handful of these authors’ titles, notably García Márquez’s “One Hundred Years of Solitude.” But it has stuck to that Mexican-Colombian literary giant, and it has fastened like a barnacle to Allende as well.

With “Maya’s Notebook,” Allende succeeds in shedding all such limiting labels. Written in the smart, engagingly blunt first-person voice of its teenage heroine, “Maya’s Notebook” purports to be the diary-like account of a young Chilean-American’s picaresque quest for love and moral enlightenment as she roams from Berkeley to Las Vegas to the Chiloé archipelago off Chile’s southern coast.

Actually, Maya Vidal, 19, isn’t roaming; she’s running for her life. She’s fleeing a scuzzy assortment of drug dealers, junkies, petty criminals and rapists, whose brutal, darkly humorous personalities and exploits are rendered in harrowingly persuasive detail. Maya falls in with this rat pack after her beloved grandfather, “Popo,” dies and she escapes from an Oregon academy for “rebellious young people ... who just didn’t fit in anywhere.” A few steps behind her, in hot pursuit, are the FBI, Interpol, and a gang of Nevada thugs.

As her story opens, Maya has been dispatched for her own safety to Chiloé to live with Manuel Arias, a mysterious old friend of her grandmother, Nini. Nini is a no-nonsense force of nature who herself went into exile a generation earlier when she exchanged Chile for Canada during the brutal dictatorship of Gen. Augusto Pinochet. Maya’s absentee Danish mother and father, a pilot, are pretty much out of the picture.

Her new caretaker, Manuel, is a flinty but kind-hearted septuagenarian who was banished to the island for being politically suspect during the Pinochet crackdown. Warily at first, Manuel and Maya forge a bond that allows the teenager to probe deeper into her family’s past. She also becomes immersed in the lives of the island’s colorful inhabitants.

“Maya’s Notebook” is a story about how parents, communities and gangs — biological, surrogate and adoptive; good, bad and indifferent — mold our identities. Its strength is Maya’s distinctive voice: vulnerable but spiked with irony, wounded yet defiant, like a teenage emo-punk’s pierced tongue. Its best stretches put me in mind of other prodigiously slangy, precociously sharp contemporary narrators such as Yunior in Junot Diaz’s “The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao.”

“I’m five-ten, 128 pounds when I play soccer and several more if I don’t watch out,” Maya informs us early on. Many pages later, during a life-threatening rape, Maya steps outside her own body to observe “the long, thin, inert female figure, open like a cross, the minotaur mumbling obscenities and thrusting over and over again, the dark stains on the sheet, the belt, the gun, the bottle.”

Occasionally, Maya’s voice-over loses a touch of credibility from Allende’s clunky invocations of contemporary pop culture. Self-conscious references to Internet porn, the current goth-teen vampire obsession, “friends with benefits,” and the correct method for ingesting crack cocaine sound more like a middle-aged anthropologist’s musings than a street-wise 19-year-old’s casual chatter. Would a hardened California teen who’s extorting money from a sugar daddy likely refer to the sucker as “an unhappy wretch?”

More significantly, in the course of its nearly 400 pages, “Maya’s Notebook” never establishes a solid and illuminating connection between the viciously lurid odyssey that Maya undergoes and the discoveries that she makes about her South American family’s own past ordeals. Most readers will easily guess at the hidden tie between Nini and Manuel that is revealed anticlimactically near the end of the novel.

Yet through its well-realized heroine’s evolving consciousness, “Maya’s Notebook” exerts a raw and genuine power. Although Allende has set previous novels in Chile (or thinly disguised versions of it), “Maya’s Notebook” offers perhaps her most visceral and urgent reckoning with the country that the ex-pat author left behind decades ago. (She is the niece of Chilean former President Salvador Allende, who was deposed and killed during the Pinochet coup.)

What Maya finally discovers through her painful journey into the self and the story she mentally composes for us is that not even a homeless, parent-less exile is truly an island. That is the book’s honest and resilient revelation, with no magic required.

Allende will discuss her new book at a LiveTalks Los Angeles event Thursday, May 16, in conversation with Patt Morrison. More information: https://livetalksla.org.

Maya’s Notebook

A novel

Isabel Allende, translated from Spanish by Anne McLean

HarperCollins: $27.99

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.