A school of hard knocks for Mr. Webb

“Ok, here it is: ‘The Graduate, Part 2’! Ben and Elaine are married still, living in a big, old, spooky house in Northern California somewhere. Mrs. Robinson, her aging mother, lives with them. She’s had a stroke. And they’ve got a daughter in college -- Julia Roberts maybe. It’ll be dark and weird and funny -- with a stroke.” So said Buck Henry, the co-screenwriter of “The Graduate,” to an indifferent studio executive in Robert Altman’s “The Player.”

The 1967 film “The Graduate” cemented the careers of screenwriter Henry, director Mike Nichols and star Dustin Hoffman. The one person who didn’t fare so well was the author of the source material, Charles Webb. “The Graduate,” based largely on his life, was Webb’s first novel, published in 1963 when he was just 24. He received $20,000 for both the film rights and the future film rights to the characters.

On Tuesday, , St. Martins will release Webb’s sequel to “The Graduate,” “Home School.” It is Webb’s eighth novel but his first to revisit the best-known of his characters. The story unfolds in Hastings, N.Y., in the 1970s, and Mrs. Robinson does indeed come to live with Ben and Elaine as they battle the Westchester school board. It’s a light, funny and satisfying book. As the book’s editor, Paul Sidey, puts it, “The sequel is not quite the same in terms of being iconic, but it has all the wit and style of the original.”

Yet the story behind the creation of “Home School” is as unlikely as any fiction. In April 2006, Jack Malvern, a reporter for the London Times, tracked Webb down to Hove, in Sussex, England. He discovered that Webb, at 66, was about to be evicted from his apartment and that he had written a sequel to “The Graduate” but was reluctant to publish it because the film rights to the characters were owned by Canal Plus. Sidey, an editor at Hutchinson Books in London, immediately reached out to Webb, and within a month a deal was in place. “I read about his plight, and I tracked him down,” Sidey said, adding, “It is very easy for people of quality to slip through the cracks, especially in publishing.” The book is dedicated to Malvern.

The reports on Webb’s life read like a cautionary tale of early success -- he has moved almost constantly during his adult life, he has held a series of menial jobs to support himself, he’s been homeless to the point that the check for his advance for “Home School” was mailed to him at a Salvation Army shelter, and he is still in debt while caring for his lifelong partner, who recently suffered a nervous breakdown. Despite the easygoing charm of his novels, one expects to meet a shivering wreck.

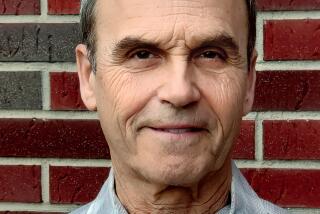

Instead, the living sequel to “The Graduate” greeted me not long ago at the train station at Eastbourne, a small town on the south coast of England. At 68, Webb is tall, thin and elegant, with a full head of gray hair, the picture of Southern California languid bonhomie set amid the drizzle and overcast skies of small town Britain. Gulls were flying overhead, the only sign that we were near the sea.

He asked if we could run an errand before talking, and we walked to the local supermarket where he spent $3 on produce (a sweet potato, broccoli and two apples) before calling for a taxi. He talked for a while about a play he is writing, concerning a celebrity journalist who slowly discovers that artists are the minority. He asked about virtual reality and second sight. We taxied to his current home, an old-age hostel of sorts.

Webb explained that the place has been a great help to him and his lifelong partner, a woman named Fred. “It’s a lot like a college dorm, except people keep dying here. Two people have died in the last 10 days,” he said with a shrug. He left me in the communal area -- a row of a dozen electric wheelchairs lines one wall -- to check on Fred. He came back down to tell me she was not feeling well enough for visitors today. Then he mentioned sunnily that he was wearing his “dead man walking jacket,” an item he recently received from a “deceased farmer.”

It’s a perfectly pleasant and friendly facility, but one can’t imagine Mike Nichols or Dustin Hoffman or Buck Henry even making a movie here, let alone residing here. The fact remains that the film version of “The Graduate” made over $120 million, that Webb received a flat fee of $20,000 for the rights to his book and his characters (in perpetuity) and an additional $10,000 after the initial success. And reading the original novel of “The Graduate,” it is striking to see how much of the novel’s dialogue ended up in the screenplay. Indelicate though it may be, surely he must at times wonder where his mansion is.

Credit where it’s due

Webb is refreshingly firm on the matter of credit. “There’s always been an implication, and in your question as well, that somehow Buck has taken credit for something I did,” he says. “I have never felt that way. My feeling is, if it wasn’t for what happened with the film, that book would have just come and gone, and it would now be as dead as can be. And with the money thing, well, I write for personal reasons. I don’t think it would have been so nice to have a lot of money. People present my position of how I got screwed and how bitter I must be, and I just don’t feel that way.” (Henry did not respond to requests for comment.)

“It’s a bit simplistic,” Webb went on, the two of us sitting in the fading light, “but I see my life as a beginning, a middle and an end. There was the writing of ‘The Graduate’ and everything that’s gone on between then and writing ‘Home School.’ I see finishing ‘Home School’ as finishing the middle part of my life, and whatever happens with the book -- or doesn’t happen with the book -- is not as relevant as the accomplishment of having finished it.”

Webb and his partner moved to England in 1999. Before that, the couple had traveled around America, running nudist camps, working as cashiers at a Kmart and taking any other jobs the couple could do together. They raised two sons, home schooling them in the 1970s when that was an illegal act considered to be truancy. They were back in West Hollywood when they decided to come to England, for no apparent reason. They took the train from L.A. to New York and then a cruise ship to Southampton. (Webb hasn’t flown since 1963.)

In 2000, long before Malvern and Sidey found Webb, who had been living in England for a year, theatrical producer Sacha Brooks was mounting a West End production of “The Graduate” starring Kathleen Turner as Mrs. Robinson. Brooks told me from his London home, “We had tried to find Charles when we were looking for the rights to the material, and two weeks into rehearsal we heard from him and he was quite moved -- it was the first time those characters had been revealed in 40 years, so he tells me.”

Webb attended several rehearsals of the play and considers that production to have been a turning point. “That really opened my eyes to what I should have been doing all along. I was in the theater, hearing my lines and hearing the reactions of the audience. The play was based on my book, and to hear some line I had written four decades ago bring down the house . . . I started seeing myself differently after the production. It all just fell into place.”

Brooks is still in steady contact with Webb. “It is abundantly clear that nobody writes dialogue like Charles,” Brooks declared. “Vast phrases in the film and the play come directly from his writing -- he is crisply brilliant without ever being forced. It was only a surprise to me that it wasn’t obvious to Charles. He does it his way -- he is a true artist.”

Around that same time, Webb began the process of writing “Home School.” It didn’t begin as a sequel at all. The book is very light, or “slight” in Webb’s words. “It doesn’t seem like it could have taken six years to write, does it?” he said, smiling. It started as a novel, then as two versions of a screenplay. “It started with just the idea of a home-school family, and the first versions were just about that family getting into trouble with a school board. But when the idea hit to have a character seduce the school principal as a favor -- that idea really intrigued me and I realized it had to be Mrs. Robinson who would be available for that particular service, and the idea of a sequel just started bubbling up.”

As he was revisiting those characters, did Webb ever envision the actors from the film? “Oh, all the time. Isn’t that strange? But, oh, yes, I could see Dustin and Anne Bancroft throughout this book.”

Always on the move

HE grew up in California, having been born in San Francisco and raised in Pasadena. His first unconventional act was to refuse an inheritance from his father, a doctor. “I didn’t want to be put into some kind of thing where you’re wondering how much you’re going to get. It wasn’t the principle of money, it was the concept of families being put at each others’ throats.”

Webb went east, to study at Williams College. While there he started writing “The Graduate” and met his lifelong partner, Eve, then a student at Bennington (she changed her name to Fred in the 1970s). When the book was published, it caused a sensation as well as a rift with his father. “He was smoldering -- ‘How could my boy do this?’ -- but after Mike Nichols got ahold of it, suddenly I was the golden boy.” He shrugged. “The film totally changed our relationship.”

After the book, the couple moved around a great deal. They lived in Hastings, N.Y., in the early 1970s and spent the next two decades moving every few years, from a nudist colony in the south of France to various towns on the East Coast and back to California.

“Something erupts and I move on,” he said. “Something new comes up and we get attracted. But look where we’ve wound up, the places we wind up are always strange, and that’s our cup of tea, whether it’s a nudist colony or a Kmart, we seem to wait until circumstances create something completely new. It’s almost as if it is only in those circumstances that ideas for stories emerge. These environments seem to release something that takes the form of stories and characters.” He waved his arms while walking around the dark communal rooms of his hostel.

Cultural comparisons

Webb has such an easygoing charm about him, such a friendly and sincere presence, that he renders his circumstances as logical and reasonable. Since throwing himself at the mercy of England, he’s been well cared for. “I’ve found it’s true that the state deals with people more humanely in England than in America, even though the complaining level over here is a national sport.” But why England? Wasn’t that wildly random, even for him? “Well,” he drawled, “You know, the reviews of my books are always intelligent here. And they tend to be favorable. Whereas in the States, the precept has always been, ‘Will this book be as big as “The Graduate?” ’ They were talking about these slight, minor novels that were never, ever supposed to be super-novels, and comparing them. And that question has never been asked over here. British reviewers just want to know if the book is any good.”

Didn’t he ever expect, after his early acclaim and success, that writing would pay his way? “Sometimes it does, and sometimes it doesn’t. It’s very nice when it happens, but something else always turns up if it doesn’t.” He mentions that he was once offered a newspaper job in Lakeville, Conn., but he refused it because Fred wasn’t also offered a position at the newspaper. The two ended up working at a local inn as a dishwasher and chef instead. After 44 years together, don’t they like a little time apart? “To stick together is more important. We seem to keep each other from being torn apart, basically.”

He’s still in debt, and the state has provided him with a financial advisor. He finds debt to be fascinating, saying that if he wasn’t in debt he wouldn’t know about debt collectors. A few years ago, Webb sold the film rights to his last novel, “New Cardiff,” for $120,000, and the book was made into the Colin Firth film “Hope Springs.” One of the first things Webb did with the money was give $20,000 to a local artist.

“People in the arts are not allowed to lead normal lives,” he declared later in the day. “They either have to be super rich, thinking about their mansions, or penniless like me. But they’re not allowed to lead lives like everyone else.”

But he’s lived his life as he has wished, surely?

“Not really, I don’t think our life is normal at all. I’m not sure, all else being equal, that I would have found being a caretaker in a nudist colony in New Jersey necessarily to be the optimum way of life.

“All this drama in my life, all this financial crisis -- it’s really playing a role. The penniless author has always been the stereotype that works for me.”

Then he says, with a real twinkle in his eye: “When in doubt, be down and out.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.