In L.A. restaurants, an eco-frenzy

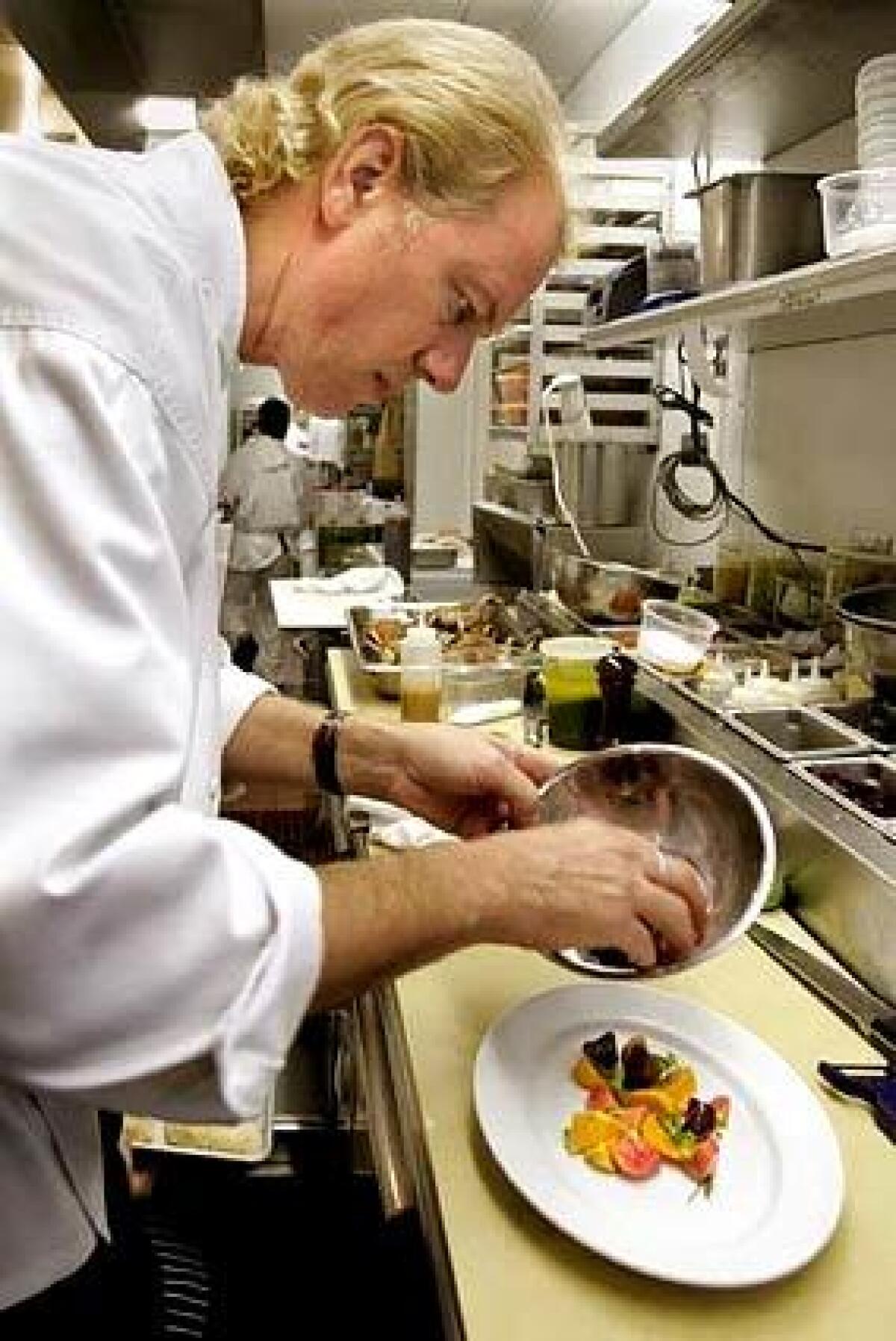

WHEN chef Christopher Blobaum was opening Wilshire restaurant in Santa Monica, he wanted to do the right thing, both culinarily and environmentally.

He buys much of the restaurant’s produce at local farmers markets and sources meat and fish carefully. He uses solar-heated water for dishwashing and low-output fluorescent lighting. The deck out back is made from recycled lumber (and is built in a way that preserves the property’s existing mature trees). Tables are set with woven vinyl Chilewich placemats that can be rinsed and reused instead of white linen tablecloths that need to be washed and bleached.

Blobaum even bought a backyard compost tumbler he keeps behind the restaurant to dispose of much of the food waste.

Remember when restaurants used to brag about organics? These days, in food as in everything else, the buzzword is “sustainable.” Every time you turn around, someone is claiming to be “green” or “eco-friendly.”

But as Blobaum learned, moving beyond the slogan stage is hard work and complicated. And despite the many claims, few restaurants are up to tackling going green in a serious way.

In large part, that’s because eco-friendly and “sustainable” are still so loosely defined that they can include a dizzying maze of factors: how the restaurant was built, how and where the ingredients were grown, the nature of the materials used to serve them, and how the leftovers are disposed of.

There are a few notable exceptions, but for the most part, chefs and restaurateurs are still trying to sort out just what “sustainable” means, and beyond that, how it fits into running a viable business.

“Learning about sustainability is an ongoing process,” says Blobaum, who is still looking at improvements for Wilshire, even after having won a Sustainable Quality Award grand prize from the city of Santa Monica this year.

“You can’t do it all in one day. It’s an education. You decide this week or this month we’re going to try to tackle this. It might be something simple, like switching a cleaner. Once you’ve accomplished that, then you move on to the next thing.”

In Blobaum’s case, the next steps he’s exploring are putting solar panels on the roof and getting a bio-diesel car for the restaurant to use.

Even with all of that, he’ll still have a ways to go before he catches up with Maury Rubin, the bicoastal owner of City Bakery in Manhattan and Brentwood, and Birdbath, the newest of which he hopes to open in Pacific Palisades before the end of the year.

The City Bakery operations are definitely eco-friendly; the Birdbaths are downright eco-rapturous. Not only does much of the produce come from the farmers market, but the flour and sugar are organic, the walls are made of wheat, and the cups are made of corn. The countertop is made from recycled paper and the paper bags have no petroleum-based wax coating. All of the electricity comes from wind power.

The delivery boys pedal rickshaws (soon to be switched to bio-diesel trucks).

“How far can it go?” Rubin asks. “It only depends on how willing you are to go down that road. I don’t think it’s the hardest thing in the world. But I do think you have to be willing to take apart the whole model of how your restaurant works and put it back together again thinking green.”

And it’s not just trendy high-end restaurants that are thinking about sustainability either. The movement has all the earmarks of being the next big thing. How big? Last summer, the National Restaurant Assn. launched a “roadmap to sustainable restaurant operations” project to guide the group’s 375,000 members toward more environmentally friendly operations.

There’s also a Green Restaurant Assn. that steers its clients toward sustainability by advocating steps such as eliminating Styrofoam containers, conserving water and power, using recycled and chlorine-free products and searching out sustainable food sources. Among its members are the 500-outlet Coffee Bean & Tea Leaf chain and the Le Pain Quotidien chain, which even has its own director of sustainability.

Staying local

STILL, despite lots of good intentions (and almost as much advertising), the push for sustainability in Southern California restaurants is still taking its baby steps.Some restaurants are working harder at sourcing ingredients that come from closer to home. At Grace, Neal Fraser has introduced a weekly “Ethical Tasting Menu,” using mostly ingredients that come from within 400 miles of the restaurant. One recent menu included caviar from the Sacramento River, prawns from Santa Barbara, sand dabs from Morro Bay and pork chops from Devil’s Gulch Ranch in Marin County.

The hardest part, he says, isn’t finding the star ingredients but the supporting players. Veal bones for making stock, in particular, were a challenge, since most veal comes from the Midwest. Through diligent digging, though, Fraser was able to track some down from a dairy herd in Central California.

Even so, what works on a special tasting menu is harder to translate to full service, though Fraser is working on it. “I’m out there digging for ingredients, but when you put something on the menu, you need to make sure you have a good supply,” he says. “With the tasting menu, the most I usually sell is 25 a night. It’s a lot easier when you’re only selling a small amount.”

And sometimes it’s not even clear what the right direction is. Is it better to buy organic vegetables that have been shipped across country or ones that have been conventionally grown close by?

Providence’s chef-owner Michael Cimarusti is well aware of the problems involving seafood. He runs a restaurant based on it and is an avid fisherman himself. Though he makes no special claims for sustainability, he does follow the Seafood Choices Alliance program and serves only fish that is rated a “smart choice.”

Seafood featured on a recent menu included Maine lobster, Dungeness crab, oysters, farmed caviar, squid, manila clams, Alaskan king salmon, wild striped bass and yellowfin tuna. There is no bluefin tuna and no caviar from Russia, both of which are seriously overfished.

Despite all of the homework he did to develop the menu, he still has questions. “It’s a difficult thing, especially now with carbon miles being considered,” Cimarusti says.

“What’s sustainable when it’s caught in New Zealand may not be considered sustainable by the time it gets to Los Angeles,” he says. “On the other hand, if I had to restrict myself only to what was caught within 200 miles, I couldn’t be a seafood restaurant anymore. Am I going to build a menu on mackerel and squid and sardines? How many of my customers will come for that?”

Sometimes making the sustainable choice saves money, but sometimes it costs — and not just for fancy equipment such as solar panels. When Chez Panisse’s Alice Waters decided to stop selling bottled water at her restaurant because of the amount of energy it took to ship it from Europe, Wilshire’s Blobaum was among those who wanted to follow suit — until he ran the numbers.

“It’s really crazy,” he says. “I put in a reverse osmosis program for the restaurant so we have perfectly clean water going to all the stations, probably cleaner than most bottled water, but we still need to sell bottled water. That’s partly because the customers demand it, but also because there’s a lot of money involved in it. To give up bottled water, I would have to give up a fair amount of extra revenue.”

Fraser says he’s getting around the problem at Grace by introducing his own house-bottled water within the next month or so. “We’ve already got filtered water with reverse osmosis; now we’re getting a machine that will carbonate it with medical-grade CO2,” he says. “We’ll price it a couple dollars cheaper than regular bottled water and it’ll be an as-good or better product.”

L.A.’s pilot program

RESTAURANTS don’t have to figure it all out on their own. There is help available. The city of Los Angeles has set up a pilot program to recycle restaurant food waste, turning it into compost.Just over 2 years old, the program now includes 175 restaurants, says its leader, sanitary engineering associate Zafar Karimi. And it is growing at a rate of 10 restaurants a month. Already, it is treating about 800 tons of waste a month.

More than 70% of restaurant waste is organic and can be treated this way. Karimi says a restaurant can reduce its paid trash pickup by as much as 75% (organic waste pick-up is free), saving a substantial amount of money.

Santa Monica is particularly aggressive about encouraging sustainability. In fact, it was through a city-sponsored program with the nonprofit group Sustainable Works that Blobaum learned much of what he uses at Wilshire.

Susy Holyhead runs the program and says she’s worked with at least 20 restaurants during the last five years. “We do a complete assessment and environmental audit of the business and write up recommendations that show them how to save money and resources. It covers a lot of things: saving water, saving energy, reducing waste output, reducing toxic chemical usage and encouraging employees to use alternative transportation.”

Still, it sometimes seems to be all a bit much.

“At the end of the day, it’s a mix of what you could do, what you want to do and then absolutely positively, what the market will allow you to do,” says City Bakery’s Rubin.

“A couple of years ago, I decided that as a restaurant proprietor, I have an opportunity. I have a couple of thousand people coming through City bakeries every day. That’s a good-sized audience. And I don’t want to look back and not have taken advantage of doing something that (a) I really care about; and (b) believe is really important.”

--

russ.parsons@latimes.com

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.