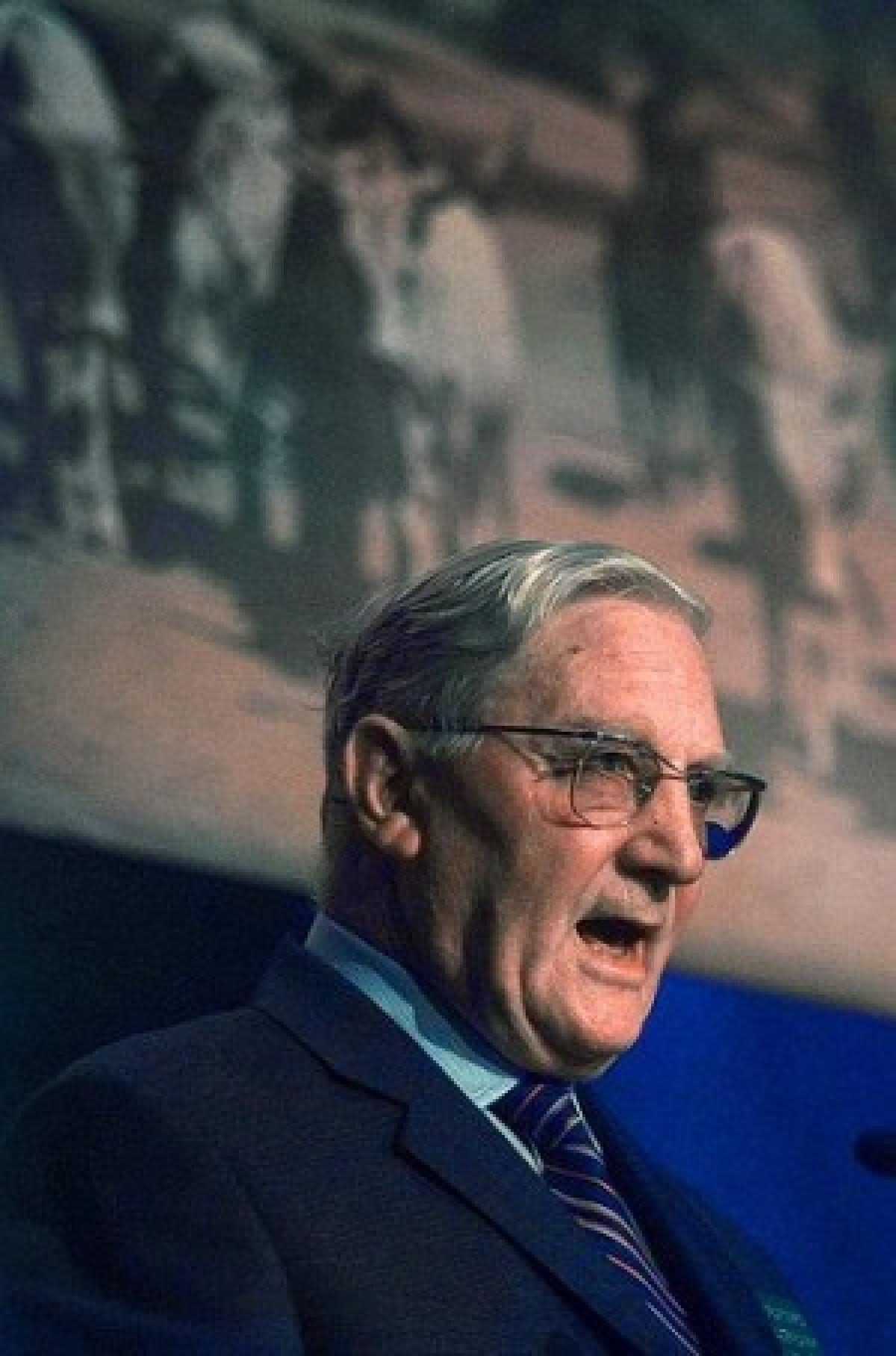

Walter Plowright dies at 86; invented vaccine that eliminated serious cattle disease

Dr. Walter Plowright, the British veterinarian often called one of the “heroes of the 20th century” because of the massive increase in meat and dairy products resulting from his invention of a vaccine that has almost totally eliminated the cattle disease rinderpest, died Feb. 19 in London. He was 86.

Most Americans have probably never heard of rinderpest, a virus in the same family as measles that causes one of the most lethal diseases in cattle. It never established a foothold in the Americas and was eliminated from Europe early in the 20th century, but its introduction to Africa in 1889 in cattle shipped from India caused what some consider the most catastrophic natural disaster ever to affect that continent.

The virus, which strikes primarily cloven-footed animals, killed nearly 90% of cattle in sub-Saharan Africa, along with sheep, goats, buffaloes, giraffes and wildebeests. The loss of plow animals, herds and hunting resulted in mass starvation that killed a third of humans in Ethiopia and two-thirds of the Masai people in Tanzania. Subsequent outbreaks further contributed to poverty and starvation in the region.

Plowright was a young veterinary pathologist assigned to the United Kingdom’s East African Veterinary Research Organization laboratory at Muguga, Kenya, when he and colleague R. D. Ferris began studying the rinderpest virus in 1956. Several groups had tried without success to develop a weakened version of the virus that could serve as a vaccine in the way that Edward Jenner had used a weak cowpox virus to produce a smallpox vaccine.

Plowright decided to use the relatively new technique of growing the virus in cells in glass tubes. After passaging the virus through nearly 100 generations of cell cultures over eight years, he and Ferris obtained a weakened version that could provoke immunity to rinderpest but did not produce disease. The weakened virus was inexpensive to produce and could be grown in large quantities.

The vaccine, called tissue culture rinderpest vaccine, was quickly adopted, but cattle growers did not initially use it for long enough and outbreaks occurred again. One such outbreak in Nigeria resulted in more than $2 billion in losses.

In 1994, the United Nations’ Food and Agriculture Organization organized a global eradication program that trained vets and farmers to recognize and control rinderpest and promoted widespread vaccinations. The last major outbreak of the disease occurred in Kenya in 2001, and the FAO is expected to declare the virus eradicated in the wild this year. Rinderpest and smallpox will then be the only disease viruses that have been eradicated worldwide.

The FAO has said that the cost of the rinderpest eradication campaign was about $3 million. That investment, the agency says, has led to an increase of $47 billion in food production in Africa and a $289-billion increase in India.

Plowright’s technique has subsequently been adopted for other viral diseases, including African swine fever, malignant catarrhal fever and poxviruses. In 1999, he was awarded the prestigious World Food Prize.

Walter Plowright was born July 20, 1923, in Holbeach, Lincolnshire, England. He graduated from the Royal Veterinary College in London in 1944 and was commissioned into the Royal Army Veterinary Corps and sent to Kenya, where he developed a lifelong love of Africa.

After the war, he returned to lecture at the veterinary college, but in 1950 joined the Colonial Veterinary Service and returned to Kenya. He returned to England permanently in 1971 for stints at the veterinary college and the Institute for Research on Animal Diseases in Compton, Berkshire. Even after his retirement, he served as a consultant to many veterinary groups.

Plowright is survived by his wife of 50 years, Dorothy.

More to Read

Start your day right

Sign up for Essential California for news, features and recommendations from the L.A. Times and beyond in your inbox six days a week.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.