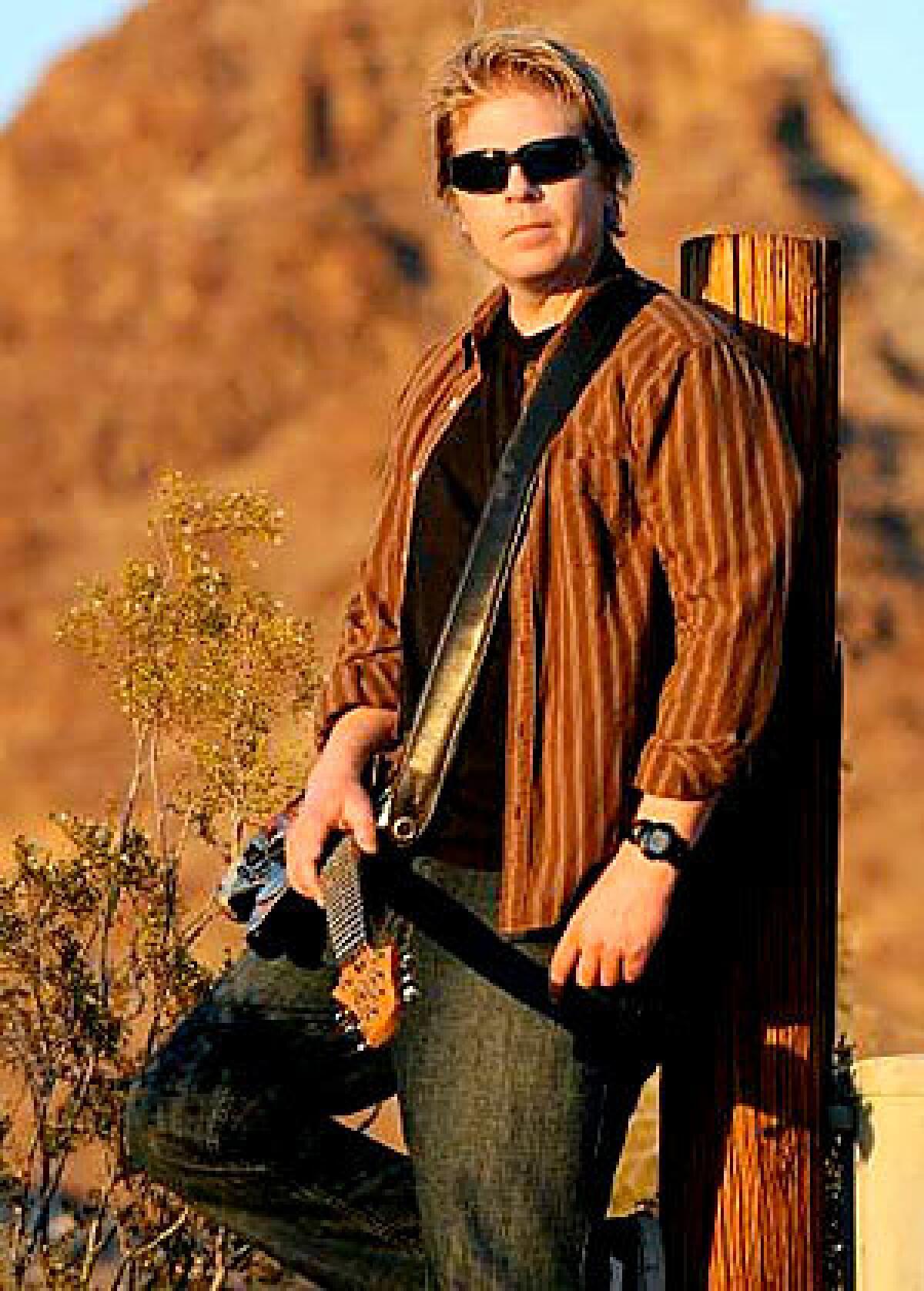

Rocker Dexter Holland’s spicy offspring: Gringo Bandito hot sauce

The Red Hot Chili Peppers, fittingly, are singing about the City of Angels on the jukebox when Dexter Holland walks into a Long Beach bar at lunchtime, pulls off his sunglasses and reaches for a menu.

Like the members of the Chili Peppers, Holland is a signature star on the Southern California rock scene -- his Orange County punk-pop band, the Offspring, has sold 17 million albums in the U.S. alone -- but on this day he is more focused on his other gig as an up-and-comer in the quirky world of boutique hot sauces.

His indelicately named Mexican-style sauce, Gringo Bandito, made its debut in late 2006 after two years of exhaustive experimentation by Holland to get just the right taste, texture and all-important zing. Bandito is now being bottled at the brisk pace of 300 gallons a month and is even being sold through Albertsons supermarkets in Southern California and Las Vegas, a triumph for a venture that faced a dizzying array of competitors and started as a spicy lark.

“Growing up here I was always into Mexican food and culture, Day of the Dead, all of it, and one day I looked at a hot sauce bottle and wondered if I could do better,” the 43-year-old Holland says as he munches on tacos at Lona’s Wardlow Station, a Long Beach landmark when it comes to cantina cuisine and cervezas.

“Making a good hot sauce turned out to be far harder than I thought,” Holland says with a weary smile. “Going to Google and typing in ‘salsa’ and finding a recipe is one thing, but trying to figure out how people make a quality hot sauce is a lot tougher. It’s guarded, somewhat, and it’s more difficult, because there’s cooking involved.”

Holland had the advantage of a background with beakers -- he has a master’s degree in molecular biology from USC, which may surprise many of his young concert fans who pogo while he belts out such Offspring hits as “Hammerhead” and “Come Out and Play.” He’s also designed and patented software for BlackBerrys, owns a record label and happens to be an experienced pilot who owns three planes.

None of that, though, matters in the burn-or-get-burned business of hot sauce.

“People take it so seriously, especially here in Southern California, where Mexican food is part of the way of life,” says Holland, who noted that youth culture in the beach towns is especially drenched in the binding sauce. “It brings all kinds of people together. The hard-core hot sauce guys carry their own bottle around with them in the glove compartment or their work box.”

What you think of when you hear “hot sauce” depends on what table you’re sitting at. There are the dips and pastes of Asia, the Scotch bonnet sauces and mustards of the Caribbean and, by far the most popular in the U.S., the family of Louisiana-style vinegar-based hot sauces, which Tabasco dominates like Coca-Cola and Pepsi put together.

Mexican-style hot sauce historically has put more emphasis on flavor than heat and tones down the vinegar, compared to the bayou counterparts. Holland says that with his Gringo Bandito, he stayed away from the contemporary how-hot-can-you-go competition that has led certain restaurants to ask customers to sign waivers before taking that first bite.

Holland is reluctant to critique competitors (he does admire an import called Amazon Hot Sauce, a green, mild, mango-flavored sauce) or to describe his own recipe too precisely -- and who can blame him after so many months of struggle? But Bandito’s “official” ingredients as listed on its website: vinegar, water, habanero peppers, jalapeño peppers, red Japanese chile peppers, more peppers, salt, mojo, spices and xanthan gum.

“It’s a witch’s brew. There are a dozen types of peppers in all, and some secret stuff,” said Matt McCollum, who is part of Holland’s Bandito team, along with Florencia Arriaga, who oversees production. Twice a month, Arriaga shops for peppers and, over six hours, cooks up 150 gallons of the sauce in a caldron at Da’kine Foods, a Newport Beach professional kitchen for boutique sauces and other bottled goodies.

The right sauce can make a meal light up, and sometimes, the more expensive concoctions can’t hold a culinary candle to the tried-and-true, often cheaper, stalwarts. Lona Lee, owner of Wardlow Station, says her customers reach most often for Tapatío, the Guadalajara-style salsa picante that launched in 1971 and is bottled in Vernon, or Cholula, with its trademark wooden cap and pequin peppers. Also popular are Pico Pica, a Mexican sauce with no vinegar at all, and El Yucateco, the best-selling brand south of the border.

Holland has skipped the advertising route, instead taking a grass-roots approach to his peppery venture.

“We took it to fire stations and electrical unions and gave it away,” he says. “I leave it at beach bars in Huntington and Redondo. The best way is to get one person to taste it and then tell their friends. Ads don’t sell hot sauce. Friends do.”

Holland’s Bandito, Lee says, is catching on, but she adds that it’s hard for newcomers in the sector to gain traction, because many of her diners never stray from tradition or, on the opposite end of the scale, never want to try the same thing twice.

That safari mentality explains shops such as Hot Licks, the hot sauce specialty store in Long Beach’s Shoreline Village that has hundreds of brands promising the best flavor or the worst oral crisis.

“There’s something really fun about hot sauce. It makes a great gift and it’s fun to talk about,” Holland says as he trails some Bandito across a chicken taco. “When I started, I didn’t know how hard it would be. But hey, when we started the band, we didn’t know how to play guitars either.”

More to Read

Sign up for our L.A. Times Plants newsletter

At the start of each month, get a roundup of upcoming plant-related activities and events in Southern California, along with links to tips and articles you may have missed.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.