Critical Mass

When the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation awarded the pro-verbial “genius grant” to Dave Hickey in 2001, it noted his “original perspectives on contemporary art in essays that engage academic and general audiences equally.” Many may have wondered if there was a typo in the line, for Hickey does not so much engage as enrage.

Traditional art criticism is a Mandarin practice: Picture a scholar dispensing views purified by decades of study and observation. Hickey rejects that. He may be learned, but he’s no snob. He cares more about how art looks than what it “means.” And he has only disdain for his job: “Criticism is the weakest thing you can do in writing. It is the written equivalent of air guitar.”

So why did the MacArthur Foundation give him $500,000? Because in Air Guitar: Essays on Art & Democracy and the newly revised Invisible Dragon: Four Essays on Beauty, Hickey takes on a host of unlikely subjects: Liberace, Siegfried & Roy, Chet Baker, Perry Mason, Norman Rockwell and pro basketball. He sees joy in the ordinary and swoons over compelling surfaces and arresting images, which puts him, he says, at odds with critics who like art they can dominate.

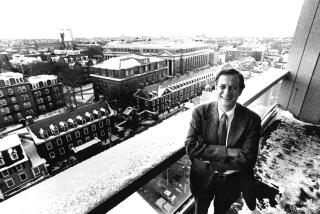

After a career that has seen him play guitar in Nashville, run galleries in Austin and New York and write for Vanity Fair and Art in America, where he has a monthly column, Hickey is a professor of English at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. He lives nearby with his wife, art historian Dr. Libby Lumpkin. That he is, at 70, enjoying life in Vegas is the final difference between him and the rest of the art world. His address isn’t an exercise in ironyhis affection for his adopted city is as unashamed as a Neil Diamond medley. Vegas, he says, is “gold on the ground,” an ideal base for a passionate populist to write “love songs for people who live in a democracy.”

Jesse Kornbluth: Were you in Vegas when you were named a MacArthur

Fellow? If so, how did you celebrate?

Dave Hickey: I was in London when the MacArthur people called. The day after I returned, the dean told me I “might be happier” in another department. The MacArthur was not even a blip on their radar. They just wanted me gone. I moved to the English department. Then they banished my wife because she walks fastthe official reason was “noncollegiality.” Today, Libby is the most widely published art historian in Nevada. She has taught at Harvard and Yale, and now she spends her days fixing up the garden. It’s too bad, because we liked teaching art students. I bought a car, an Oxford English Dictionary and a complete set of Charles Lamb with my MacArthur money. The rest made up for what our teaching fiasco cost us.

JK: You’ve written, “I am certain of one thing: Images can change the world.”

Do any images in Las Vegas really have that power?

DH: Vegas has three lessons for design in the USA: One, it doesn’t have to be boring; two, it doesn’t have to be ugly; three, it doesn’t have to “all fit together.”

JK: Okay, I’m bracing myself. What does the enfant terrible of art criticsthat’s youthink about former Guggenheim Museum Foundation director Thomas Krens, the enfant terrible of museums, and the Guggenheim Hermitage Museum he opened at the Venetian?

DH: Steve Wynn exhibited the first-rate real deal at the Bellagio. The Las Vegas Guggenheim did not. They never really showed anything that was worth flying in to see. All the curating came through the New York Guggenheim. The top-line loans that were promised from St. Petersburg and Vienna never materialized. That failure can be laid at the feet of Krens, who supplied second-rate wall filler because he is a lazy snob who didn’t have the goods. And Rem Koolhaas’ death-camp-gallery setting didn’t help. The Las Vegas Guggenheim shows would have been great for Amarillo but not for Vegas, where even the most retarded hillbilly can smell a hustle.

JK: You’ve often slammed the patriarchal world of critics and foundations. But doesn’t the reces-sion make you reconsider? Doesn’t art need the imprimatur of grown-ups and the patronage of the rich?

DH: Grown-ups are no fun. Ideally, a coherent peer society of younger artists would replace the whole extant structure with new talent, new dealers, new critics and new collectors.

JK: You’ve written of Vegas that “people revel here who suffer at homeare free here who would otherwise languish in bondage.” Do you really think people who live and work in Vegas are free?

DH: Living in Vegas is like living at the beach. Everybody would rather be here doing anything than where they came from doing something better. Ask yourself: banker in Missoula or valet parker in Vegas?

JK: How is neon more beautiful than a sunset?

DH: Neon is real and omnidirec-tional. Sunsets are mostly an idea.

JK: Dave Hickey’s night out: What’s it like?

DH: Nights are for amateurs. People in Vegas work. I get up at 3 or 4 a.m., write until 9, do business until 2 p.m. Then I read or go play cards and get home in time to watch all the NBA games, upon which I place the occasional wager. We eat at Sinatrathey make their own pastaMichael Mina, Daniel Boulud, Joël Robuchon at the high end. Otherwise, it’s El Choncho or Lindo Michoacan.

JK: Would you remarry your wife in a Vegas wedding chapel?

DH: We married the first time in a Vegas wedding chapel, in the “gazebo.” Next, maybe we’ll rent a convertible and do the “drive-thru.” A small dream but a dream nevertheless.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.