Ayn Rand’s epic storytelling

By Richard Rayner

The new, 50th anniversary edition of Ayn Rand’s novel “Atlas Shrugged” (Signet: 1,080 pp., $8.99 paper) -- appearing only three years after an edition commemorating the centennial of the author’s birth -- comes with one of those weird business reply postcards pasted in the middle, a relic of a bygone publishing era and a testament to the continuing power of the Ayn Rand Institute, which handles the Rand copyright and requires Signet to include the cards. In life, Rand became a cult figure; 25 years after her death she’s big business and still very much a force. New generations of students discover her work, reaching not for short nonfiction books such as “The Romantic Manifesto” or “The Virtue of Selfishness” but for two dauntingly massive novels, “The Fountainhead” and “Atlas Shrugged,” which continue to sell hundreds of thousands of copies a year. There’s good reason.

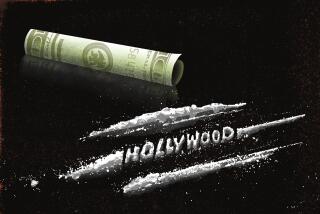

Rand fancied herself a philosopher and had determined ideas about how society was going and should go. She loved capitalism the way Romeo loved Juliet, romantically and dangerously. For an appearance on the “Tonight Show,” she wore a sweeping dress emblazoned with a golden dollar sign. She admired Mickey Spillane (for his morals!) yet considered Nabokov’s “Lolita” evil. Her stated idea of depravity was not a murderer or child abuser but a “man without purpose.” She once said that America treated businessmen the way the Nazis did Jews. She meant to be provocative but came off sounding not merely offensive but silly. But then, her true and always-underrated gift was fiction. In this, she was very much a product of the homeland she left, Russia, where polemic has a habit of getting in the way of art and craft.

Rand is still read because she was a terrific novelist. Both “The Fountainhead” and “Atlas Shrugged” hurtle the reader along with the force and velocity of the soaring machines (trains, planes, elevators) that she loved to mythologize. In part, this is due to structure. When Rand moved to Los Angeles in the 1920s, before she became successful enough to buy the glass and steel Richard Neutra house that had belonged to director Josef von Sternberg, she worked first as a film extra and then a screenwriter. The experience told. Her two enduring works are masterpieces of plotting.

In “The Fountainhead,” the formula is simple. Visionary architect Howard Roark -- Rand said she modeled the character on Frank Lloyd Wright, and Wright, who understood the value of publicity, played along with it -- doesn’t have just one antagonist. Every character in the book is his enemy, even the woman who loves him and must finally bend to his steely will. His adversaries pop up one after the other and try to destroy him. They are cunning and often lily-livered but successful in the ways of the world.

“What do you think about me?” says smooth society architect Peter Keating, who takes Roark’s designs and bastardizes them.

“I don’t think about you,” Roark superbly replies. By the time Roark finally triumphs, the average reader’s identification with him is indelible and complete.

“Atlas Shrugged” pulls off a much more intricate narrative coup. The heroine, Dagny Taggart (the brainy, long-legged and indomitable force behind the Taggart Transcontinental Railroad, apparently to be played by Angelina Jolie in an upcoming movie), finds herself in an America that is breaking down and growing shabbier by the day. Nothing works anymore. Not until more than halfway through the book, when Dagny crashes a plane in Colorado and discovers a kind of capitalist Shangri-la, is the mystery resolved. The world’s prime movers have gone on strike, led by John Galt, a scientific superman who puts even Roark in the shade. After all, while Roark merely pursues the uncluttered realization of his visions, Galt seeks to bring America to its knees before remaking it after his own ideal.

It’s page-turning stuff, though Rand offers more than a swift succession of “Da Vinci Code”-style story beats. Her descriptions of buildings and landscapes are often brilliant, and she was good at letting the physical world stand for emotion or state of mind. “There was a cold wind outside,” she writes, “sweeping empty stretches of land. He saw the thin branches of a tree being twisted, like arms waving in an appeal for help. The tree stood against the glow of the mills.” She also excels at evoking the peculiar weightlessness of a big party; her understanding of the ruthless dynamic of social competition recalls the sharpness of Jane Austen and suggests that Rand herself was the snubbed outsider at a Hollywood party or two. Stir in the scarcely repressed sado-masochism that tingles through every sexual encounter and you get the Randian fictional brew, a little silly, pretty weird, but thrilling and highly effective.

For decades, critics have scorned Rand for creating paper-thin characters while millions of readers have found that Howard Roark and Dagny Taggart live with them forever. Clearly, she was doing something right. Her message -- that each individual can and must without help blaze his or her own path through life -- is inspiring, even to those who might already have learned better. More than this, though, it’s the texture, the warp and weave of “The Fountainhead” and “Atlas Shrugged” that compels. Rand called her philosophy “objectivism,” yet the inside of her head, as revealed by these two novels, so much greater and richer and stranger than the simplistic slogans that tend to be adduced from them, was happily unique.

An exhibition celebrating the 50th anniversary of “Atlas Shrugged” opens at the Frances Goldwyn branch of the Los Angeles Public Library in Hollywood next month.

Richard Rayner is the author of several books, most recently the novel “The Devil’s Wind.” Paperback Writers appears monthly at latimes.com/books.

More to Read

Sign up for our L.A. Times Plants newsletter

At the start of each month, get a roundup of upcoming plant-related activities and events in Southern California, along with links to tips and articles you may have missed.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.