A history of L.A.’s gay bar scene, told in matchbooks

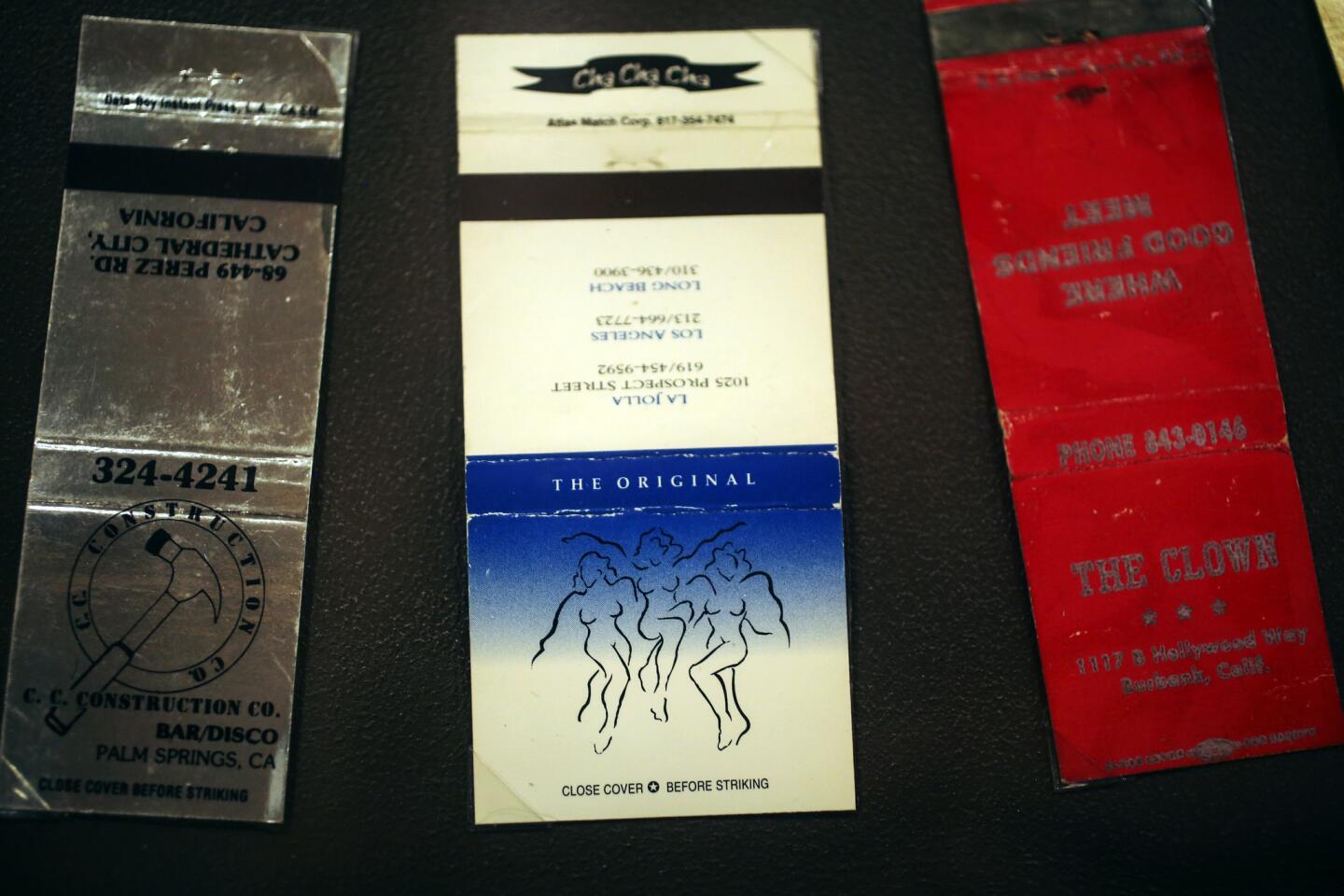

A time capsule of L.A.’s bar history is now on display at downtown’s Central Library. In the midst of the exhibition “21 Collections,” which fills the Getty Gallery with doll hats, bird eggs and Tom Hanks’ stockpile of vintage typewriters, sits a round, glass-topped case containing 200 alphabetized matchbooks from L.A. gay bars and sex clubs, most of them now closed. Elegantly arranged in concentric circles, the matchbooks hail from such evocatively named establishments as the Sewers of Paris, Basic Plumbing, the Meat Rack, the Big Banana, the Fallen Angel and Dude City.

Todd Lerew, program manager at the Library Foundation, the private nonprofit that oversaw “21 Collections,” curated the exhibition. “It’s like an archive of safe spaces,” Lerew says of the collection. “[These were] sites of solidarity. Many of them are gone now and [the matchbooks] are the only record they ever existed.”

The matchbooks have made the library a draw for former patrons of the bars. “People go through and look for places they remember,” says Lerew. “[They] have a very strong emotional connection. These are souvenirs from experiences which could have been life-changing moments.”

Jonesy, a mononymous L.A.-based queer artist who was a regular at a number of these spots worked briefly as a barback at Cuffs, a major gay hangout of the recent past.

Cuffs “was incredibly dark and super cruisey,” Jonesy recalls. “Bar service stopped at 2 but they kept it open until 3 and the lights went out for that final hour. Working there was a real challenge,” he says with a laugh, “especially when you were trying to clean up using a tiny penlight.”

Jonesy, along with a group of artistic collaborators, threw a party last summer that re-created Cuffs in the same space it once inhabited, now home to the Hyperion Tavern. “As Silver Lake — and the whole landscape of gay Hollywood and the east side — changed so much I always had this idea in my head of turning the place back into Cuffs for one night,” he says. “When I started coming to L.A. in the early ’90s, there were more than a dozen [gay bars] on the east side. You would make the rounds rather than just go to one place. Each bar had its own identity. Now things are much more concentrated and assimilated. It’s lost some of the freakishness and the weirdos, which I miss. You have three bars on the east side that people go to: the Eagle, Akbar, and the Faultline. But I don’t want to completely dog what we have left. The Eagle is my regular bar, and I’m thrilled to have it.”

The closing of many east-side gay bars can be blamed, in part, on gentrification’s effect on rents. It also can be argued that the ongoing expansion of just what queerness can mean could have made a segment of gay bars, which thrived in a sort of self-identified exclusivity, obsolete. “I’m not one of them,” Jonesy says, “but a lot of gay men my age and a generation older like to talk about the days of male-only spaces and what that meant to them. Personally, I like for anybody who wants to be involved to be involved.” Jonesy is pleased that anyone who identifies as male — trans men, for example — are now more welcome at gay bars than they were in the past. It’s interesting that these matchbooks can represent, in this way, loci both of freedom claimed outside the square world, but also an unfortunate breed of inter-underground repression.

A third factor in the shrinking number of gay bars in L.A. might be the advent of hook-up apps. “There’s this insane history of cruising in Los Angeles and it doesn’t exist anymore,” Jonesy points out. Most of the matchbooks in this collection represent potential stops on a night’s tour, such as the ones chronicled in Angeleno author John Rechy’s 1977 nonfiction book “The Sexual Outlaw,” which is like a horny version of “The Odyssey.” But when one can simply fire up Grindr or Scruff and find a casual encounter from the comfort of one’s couch, why waste gas and money going from bar to park to bar?

The matchbooks on display at the library, nostalgic artifacts adorned with images of muscled Adonises and punning slogans, were everyday objects — used and discarded — at the time they were made. They’ve resurfaced today to give us a visceral whiff of what it felt like when L.A.’s gay bar scene was headier, wilder and perhaps more excitingly illicit.

“21 Collections” has been extended to March 24.

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.