At Model Matzah Bakeries, kids have matzo down pat

The children settle down on the floor of the palace, or what passes for a palace in the Chabad center in Westwood in the frenzied weeks leading up to the Jewish holiday of Passover. Rabbinical student Zalmy Folgerman, playing Pharaoh, dismisses Moses with a borscht belt flourish.

“Noses?” he asked. “I don’t know a Noses. Bring him a tissue and let him go.”

Funny guy, this Pharaoh.

From the palace, the kindergartners move to a “farm,” where they separate kernels from wheat stalks. A few young volunteers from Valley Beth Shalom Day School grind them into flour as their classmates chant, “Turn it! Grind it! Crunch it!”

Then dough is made. A “water boy” and a “flour girl” go into two booths with a plank running between them to hold the stainless steel mixing bowl. From each booth, a window opens toward the bowl, and the flour is poured in. Then the water.

But it’s impossible for the children to work as quickly as professionals.

“The matzo we are making is not kosher for Passover. It’s kosher, but not for Passover,” says the farmer, played by Naftali Shmukler.

When observant Jews sit at their Seder tables tonight, the first night of Passover, they have made the utmost effort to remove any trace of leavened food from their homes -- even the slightest crumbs in the back of an oven. In the place of leavened bread comes matzo, a bland, crisp, unleavened bread that symbolizes both bondage and freedom.

Three unbroken matzot, usually stacked in a special cloth cover, are used in the ritual of a serious yet joyous spring holiday as the diners tell the story of the Jews’ exodus from Egypt and liberation from slavery 3,000 years ago.

And while other symbolic foods play parts in the Seder feast too, it is matzo that takes the central role, so much so that the holiday is also known as the Festival of Matzo. Over eight days, Jews are called on to eat no leavened foods -- breads, cakes, cookies -- and home cooks use matzo to make lasagna, combine with eggs in matzo brei, cover in chocolate and slather with jam.

Making matzo is an exacting task: From the moment water hits flour to make the dough to the taking of the matzo from super-hot ovens, the process can take no longer than precisely 18 minutes -- the point when leavening begins, according to the Talmud.

Matzo, and humor

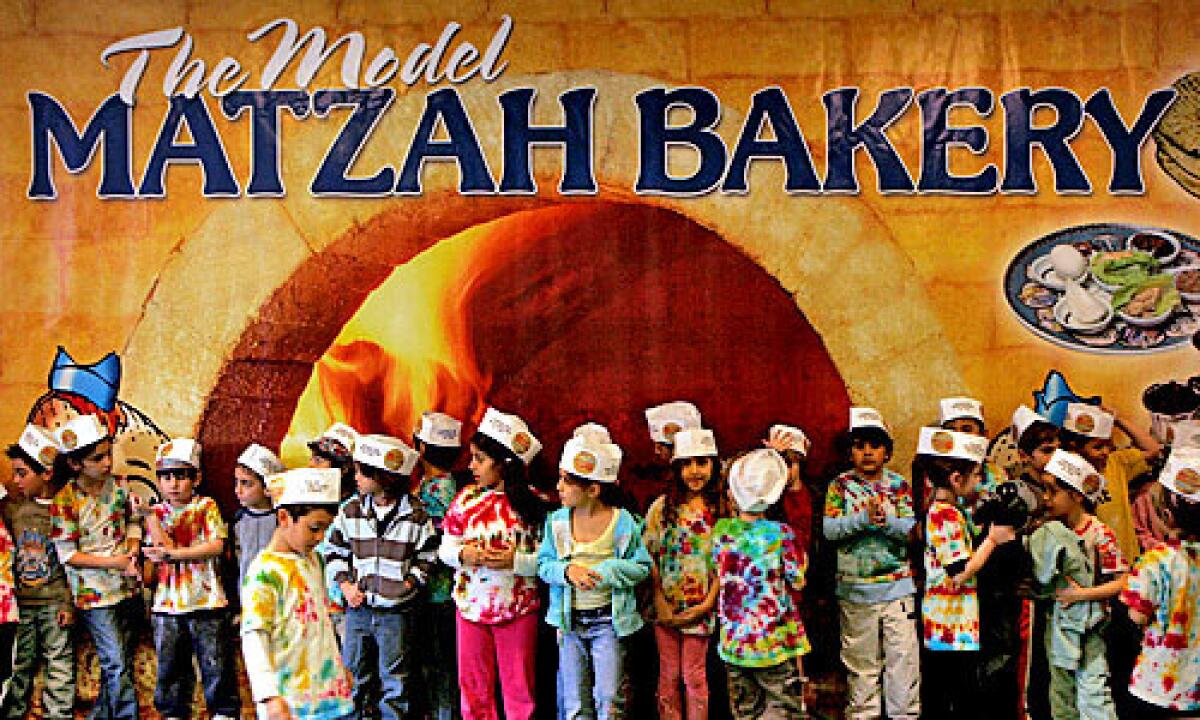

Over the last two weeks, thousands of children around the world have learned the rigors of matzo making and the history of Passover -- spiced (unlike the matzo) with a generous share of goofy humor -- at Model Matzah Bakeries run by Chabad, the outreach organization of Lubavitcher orthodox Jews.

Passover preparations are “not just an ancient tradition. To them, it’s very practical,” said first-grade teacher Rabbi Moshe Tropper, who one recent morning accompanied a group of 5- to 7-year-old boys from Emek Hebrew Academy, an orthodox day school in the Valley, to the Chabad West Coast Headquarters near UCLA.

“Passover is just eight days a year,” said Yaakov Pearson, a rabbinical student from Miami who came to L.A. to manage the model bakery this year, its 25th. “People are very strict with it.”

And little could be stricter than making matzo that is shmura, or guarded, meaning that the wheat is watched from the time of harvest to prevent contact with water and any risk of leavening. It is this process that is reenacted at the model bakery.

In actual bakeries, as in the demonstration, water and flour are kept in separate booths. From one side, flour is measured into a bowl in the center. Then, from the other side, water is poured into the flour. At that moment, a timer starts counting down 18 minutes. And the rush is on to the oven, where the temperature, Pearson said, is more than 700 degrees. In that heat, matzo cooks in seconds.

After each batch is made, the rolling pins, the dockers used to pierce the dough and the long poles used to put the matzo into the oven are sanded clean. The bakers discard aprons and gloves; new tablecloths are laid. “It’s insane. People are running around. It’s like the stock market on Wall Street,” Pearson said.

Such round matzo is made in bakeries that open just for Passover, and in only a few places -- including New York City, Montreal and Israel, Pearson said. At around $23 for a 1-pound box, it is quite a lot more expensive than factory-made matzo.

‘Very, very busy’

A man who answered the phone at the Shmura Matzoh Bakery in the Boro Park section of Brooklyn, New York, a full four weeks before the holiday laughed when asked if he would talk about the bakery’s work. “I don’t have time. It is so busy here. Now it’s very, very busy,” he said.

David Eskenazi, manager of the Kosher Club grocery store on Pico Boulevard near La Brea Avenue, said that for the Seder dinner, his family eats hand-made shmura matzo, which he described as thinner and crisper than ordinary matzo.

However, “it’s expensive for the whole holiday,” he added. So, for the rest of the holiday, he and many other people will switch to factory-made matzo.

The best-known story of matzo’s origins is that as Jews prepared to flee bondage in Egypt, they had no time to let their bread dough rise before baking it.

But Tropper points out that that story doesn’t take into account that “we were preparing for six months to leave. . . . We could have prepared a couple of corned beef sandwiches.”

Joking aside, he noted that matzo, the “bread of affliction” -- cheap, portable and nonperishable -- was fed to Jewish slaves.

“It’s symbolic of the Jews’ struggle throughout the ages,” Tropper said. “Even at our weakest, poorest point, we share what we have.”

Matzo also is a sign of humility.

“The dough rising represents the ego, haughtiness,” Pearson said. “One of the lessons of Passover is to get rid of our ego, to reflect.”

For such a weighty symbol, a trip through the Model Matzah Bakery is raucous.

Pearson and six other rabbinical students have transformed the social hall into several stations, ending with a bakery, a room full of long, paper-covered tables.

The floor has been covered with fake grass to protect the carpet. Each place has a dowel, a docker, flour and a hunk of dough.

As the children put on hats printed with the words “I baked my own matzah at the Model Matzah Bakery,” Shmukler -- now in the role of chief baker -- says, “Secure your hat before your friends’.”

Under his direction, the kids roll the dough to rounds the size of pita -- though sometimes misshapen -- and puncture them so they stay flat when baked. By this point, many children are wearing as much flour as they have kneaded.

“Simplicity is the key if you want to make a nice matzo,” Pearson tells them.

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.