Amid winemaker strife, deals in Saint-Emilion wines

Saint-Émilion in France’s Bordeaux region might have the world’s best wine classification system. It certainly has one of the most contentious, having prompted lawsuits, split families and caused polite French vintners to use English expletives about each other -- all because of efforts to keep rankings up to date.

Three years of court battles and government intervention over the last classification were covered blow by blow in the French and British press. But Americans don’t seem to care, and even some Bordeaux experts don’t have a clue how Saint-Émilion’s system works. It makes one wonder if the strife is worth it.

“The French have their own ideas on how they do things,” says Christian Navarro, partner at Wally’s Wine & Spirits in L.A. “In America, we’re a little different. We buy things based on what we think are the highest-quality wines. The American mind is a little fresher in thinking.”

The good news is, as a result of that ranking system, some very good Saint-Émilions are relative bargains in Southern California wine shops.

At the heart of the controversy is the fact that Saint-Émilion’s official rankings are supposed to be adjusted every 10 years, and it’s just as easy to go down as up.

Some say this has had the benefit of making underachieving wineries work harder.

“The fantastic revolution that has been made in Saint-Émilion over the last 20 years is because of the classification,” says Hubert de Boüard de Laforest, owner of Chateau Angelus and president of the Saint-Émilion Wine Council until 2008.

“People think, ‘We can work, maybe we can raise our classification.’ Look at what the people did who have been declassified. They never worked so hard as in the last three years.”

Contrast that with the ranking across the Gironde river in the Medoc, which was set in 1855 and has had only one promotion and no demotions in the last 153 years. That system is famous and memorable but has allowed wineries to get lazy for decades with few repercussions.

Complex varietal

Unlike the Medoc, which is best known for its big estates, Saint-Émilion has 800 mostly tiny wineries crammed into two-thirds as much vineyard space as Santa Barbara County. Merlot is the dominant grape, with most wineries also using Cabernet Franc and some adding Cabernet Sauvignon.

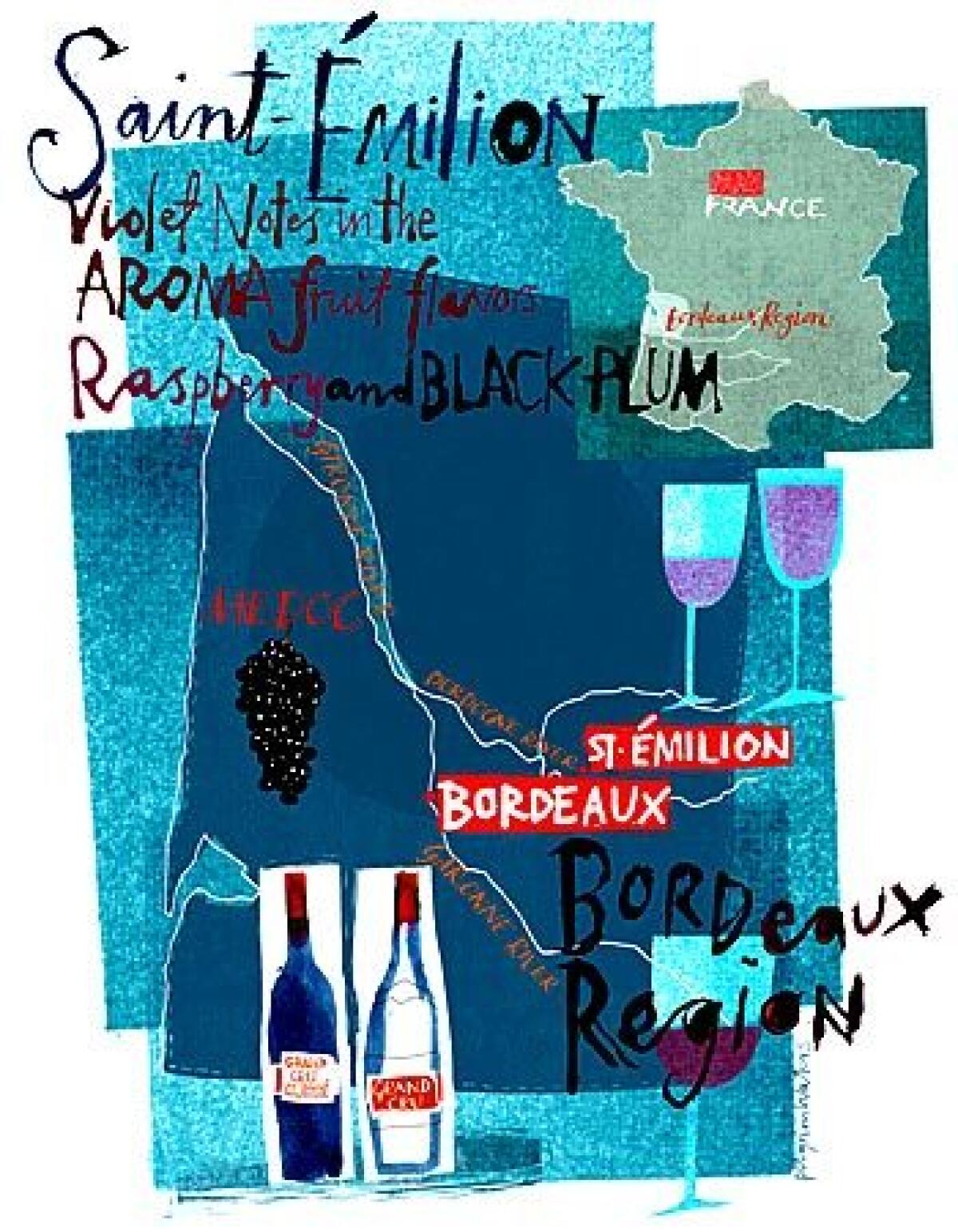

Good Saint-Émilions can be enjoyed four to 40 years after harvest. They’re not at all like California Merlot-based wines; the strong tannins can be a shock to someone expecting a mild red. But they have terrific complexity. Many have pretty violet notes in the aroma, and the fruit flavors include raspberry and black plum. They vary a lot based on the soil, and every vintner can describe his dirt in excruciating detail.

This is why the classification system is useful, but it is very French. In Saint-Émilion, wineries have to apply to be classified or promoted. They present evidence of their soils and 10 vintages of the wine in their bottles, and a panel decides whether they’re worthy.

Only 72 wines are classified. Producers of two expensive ones (La Mondotte and La Tertre Roteboeuf) haven’t even bothered to apply because high ratings from Robert Parker make it unnecessary.

Only two have been granted Premier Grand Cru Classé A: Cheval Blanc (Miles’ prized possession in “Sideways”) and Ausone. They sell on pre-release for $600 and $950 respectively, compared with about $150 for the unclassified Parker stars.

Premier Grand Cru Classé B has 13 wineries. The remaining 57 are Grand Cru Classé. That word “Classé” is important, because more than 700 wineries can call themselves “Grand Cru” just by keeping their yield below, and alcohol percentage above, certain easy targets. About 60% of the appellation’s production is “Grand Cru,” so the term is relatively meaningless, while “Grand Cru Classé” is worth suing for.

“It’s confusing,” says Clyde Beffa, co-owner of K&L Wine Merchants. “It’s not quite as easy as the 1855 classification for the Medoc.”

The current conflict started when wineries demoted in 2006 sued, arguing that the tastings weren’t blind. It quickly got personal. In Saint-Émilion it’s impossible to untangle the judges’ business and family ties.

“Why are they declassified? Because they made bad wine. End of story,” growls Xavier Pariente, proprietor of Troplong-Mondot, which was promoted to Premier Grand Cru Classé B in 2006.

But the declassified wineries won and the 2006 classification was thrown out, sending the rankings back to 1996. This prompted Pariente to file an appeal.

“One thing that hurt us is that nobody stood up for us. They are like rats,” says Pariente, who also claims he irritates neighbors by hiring gypsies -- who face discrimination in much of France -- to work in his fields and cellars. “We worked a lot to improve our wine, for years and years. One day we were rewarded. And now we are the bad guys.”

After several legal twists and turns, the French government uncharacteristically soothed everyone with a footnote to an agricultural law in May 2009 that allowed all 2006 promotions to stand, while demotions did not. The deal lasts only through 2011, though, so Saint-Émilion vintners are already preparing for civil war again.

“We think people will go to the court when they are declassified,” says Jean-Francois Quenin, owner of Chateau de Pressac and current president of the Saint-Émilion Wine Council. “So we think the people doing the classification must be completely independent.”

Going our own way

The websites of two of Southern California’s leading Bordeaux sellers -- Wally’s and K&L -- show how unimportant the rankings are here. Both list scores by Parker and Wine Spectator, but neither gives the official classification.

What this means is opportunity. In the rest of the world, Saint-Émilion prices roughly follow the classification. Here, you can find two levels of bargains: Premier Grand Cru Classé B wines less than $50, and Grand Cru Classé wines under $30. You can pre-order the 2008 Pavie-Macquin, promoted to Grand Cru Classé B in 2006, for $49 from K&L.

“My customers know Pavie-Macquin is really top quality,” K&L’s Beffa says. “Whether it says Grand Cru or Premier Grand Cru Classé on the label, that doesn’t really matter.”

More to Read

Eat your way across L.A.

Get our weekly Tasting Notes newsletter for reviews, news and more.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.