Murals, a floor-to-ceiling fantasy

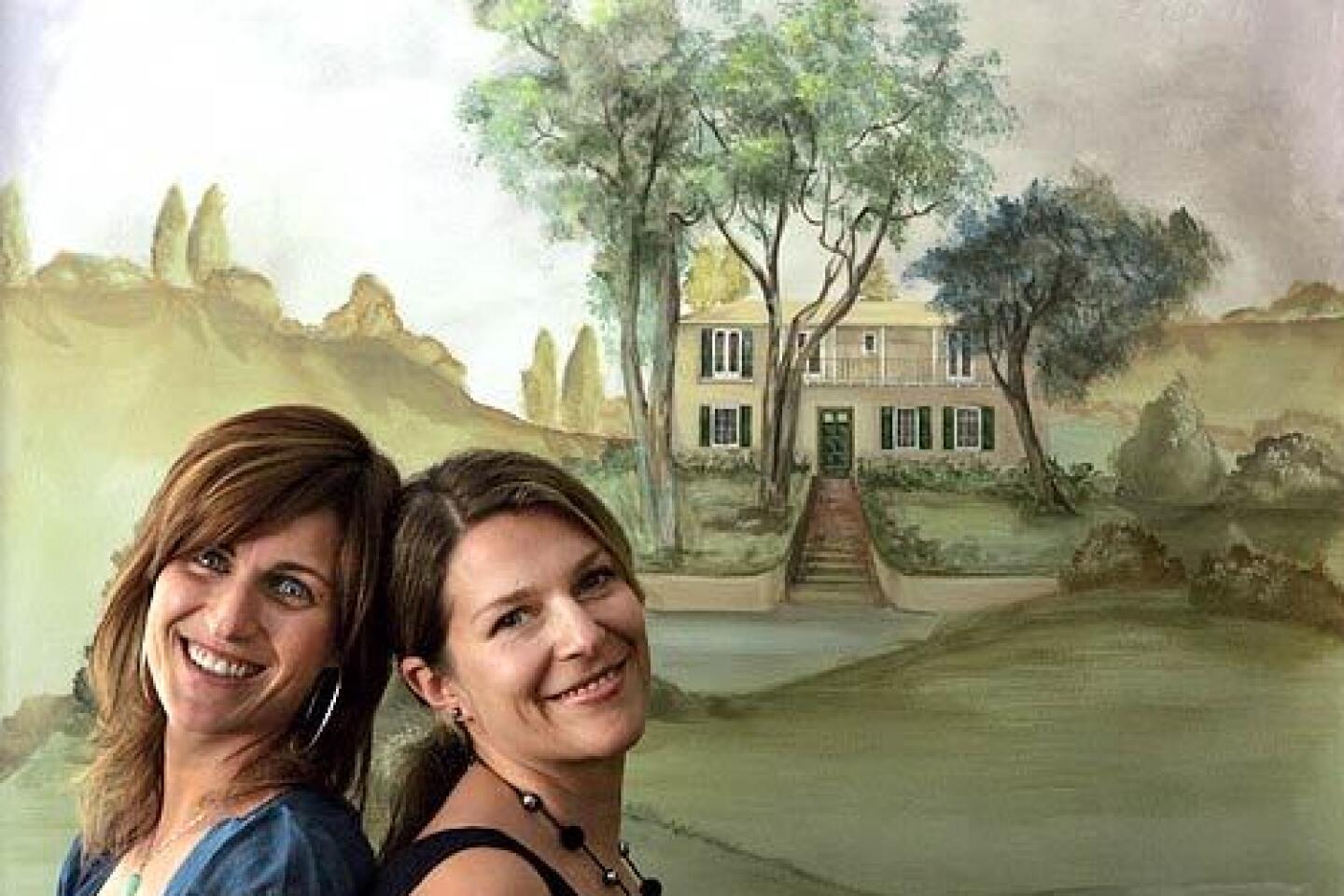

IN the design empire of Los Angeles, where Modern is king and where clean lines and empty spaces have come to define so many castles, it’s something of a surprise to see a resurgence of frescoes, murals and other painterly effects. But sure enough, Cher is working with designer Martyn Lawrence-Bullard on new interiors that will include dozens of Buddhas and scenes of ancient India painted on the walls by Kelly Holden. Oliver Stone hired artist Nancy Kintisch, who cites Bette Midler and Candice Bergen as clients, to transform his dining area into a deep red, East Indian-style affair. Hutton Wilkinson, who carries on the work of legendary designer Tony Duquette’s studio, is embarking on a five-year overhaul of Sophia Loren’s former home in Thousand Oaks for a young British couple, who are considering a western theme with hand-painted elements.

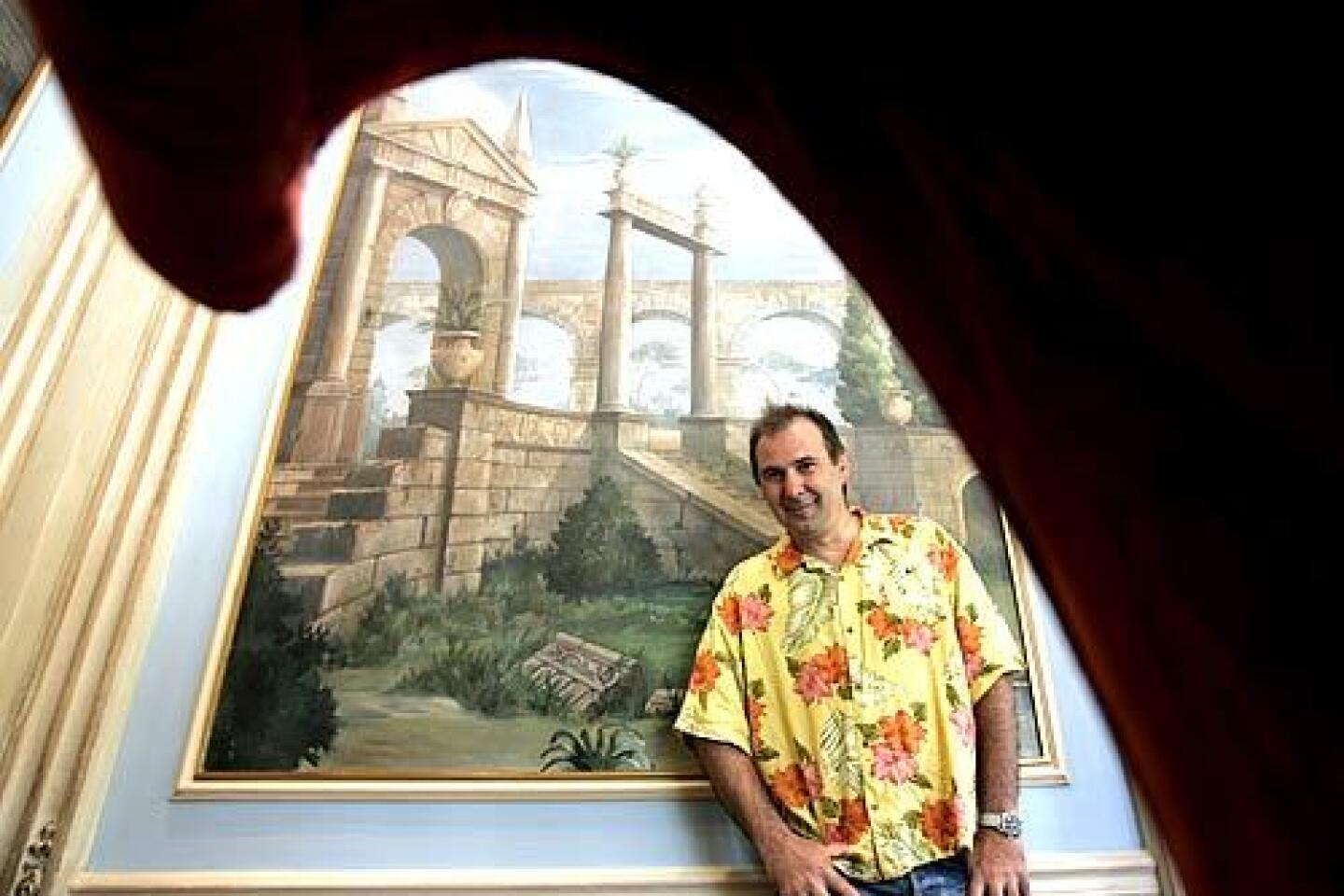

Think of the trend as a sequel to the 1930s, ‘40s and ‘50s, when, despite the rise of midcentury Modernism, Los Angeles witnessed the creation of some of its richest interiors thanks to the likes of designers William Haines, James Pendleton, Billy Baldwin and the most opulent of all, Duquette — all of whom incorporated murals in the homes of the rich and famous. “The whole idea back then, as it is today, is to encourage a kind of daydreaming,” artist Bruce Tunis says. “It sparks creativity, which is something people have always responded to in L.A.”

Adds interior designer Antonia Hutt: “It makes sense. We’ve been through some very difficult times, so I think it’s natural for people to long for a bit of escapism and fantasy.”

Today, that fantasy isn’t bound by Tuscan landscapes, trompe l’oeil and other traditional works that may make Modernists cringe. In some cases, clients are asking for fresh interpretations of classic motifs and techniques. Artists are delivering bold, abstract statements and unconventional color. The result is not so much the revival of an old art form but the reinvention of it.

Holden, for example, was trained in ancient fresco techniques in Italy, but she and Lawrence-Bullard recently brought a contemporary Indonesian touch to Cheryl Tiegs’ house. As with Cher’s project, Tiegs’ wall paintings aim to find the delicate balance between the casual and sophisticated.

“They’re both absolutely mad designs,” Lawrence-Bullard says. “You could say they’re both flights of fantasy, very romantic and very personal.”

*

IN the early days of Hollywood, figurative wall imagery was common throughout the homes of the well-to-do.

“Adding original, hand-painted elements to the home was a big deal in the 1930s and ‘40s,” says veteran interior designer Ron Wilson, who has an Asian-influenced scene painted in his dining room in Beverly Hills. “And that’s mostly to do with Hollywood, because the stars lived in homes that were generally Spanish, Italian or Mediterranean, and those homes lent themselves very well to stenciling and hand-painted touches.”

Those decorative elements quickly evolved into large-scale artworks, says painter Darren Waterston, who believes the origins of wall murals here can be traced to the movie industry’s penchant for storytelling and the desire to give spaces a pictorial narrative.

“There was a definite relationship between murals and theatrical sets,” Waterston says.

The movie colony routinely hired the same scenic painters who worked on movie theaters and set designs to create picturesque imagery in homes. Anthony Heinsbergen, whose commissions included Los Angeles City Hall, the nearby Biltmore hotel and virtually every movie theater downtown, carried the highest profile.

But there were others — scenic artists such as Hugo Ballin, who went on to direct classic silent films including “Jane Eyre” in 1921; Kay Nielsen, whose 1930s sketches for “The Little Mermaid” were inspiration for the 1989 film; and Haldane Douglas, who went on to be the art director on “The Glass Key” in 1942 and “For Whom the Bell Tolls” in 1943.

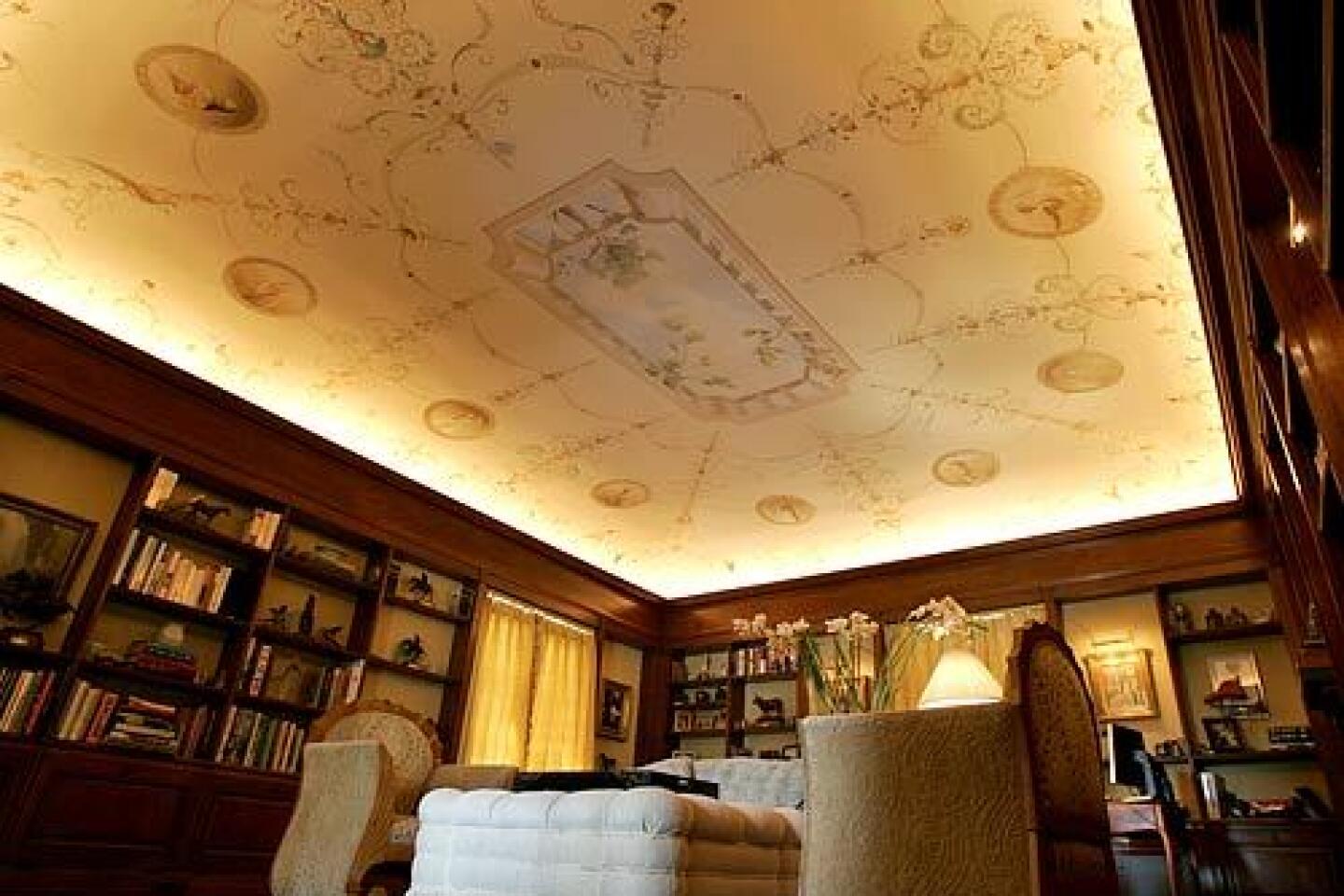

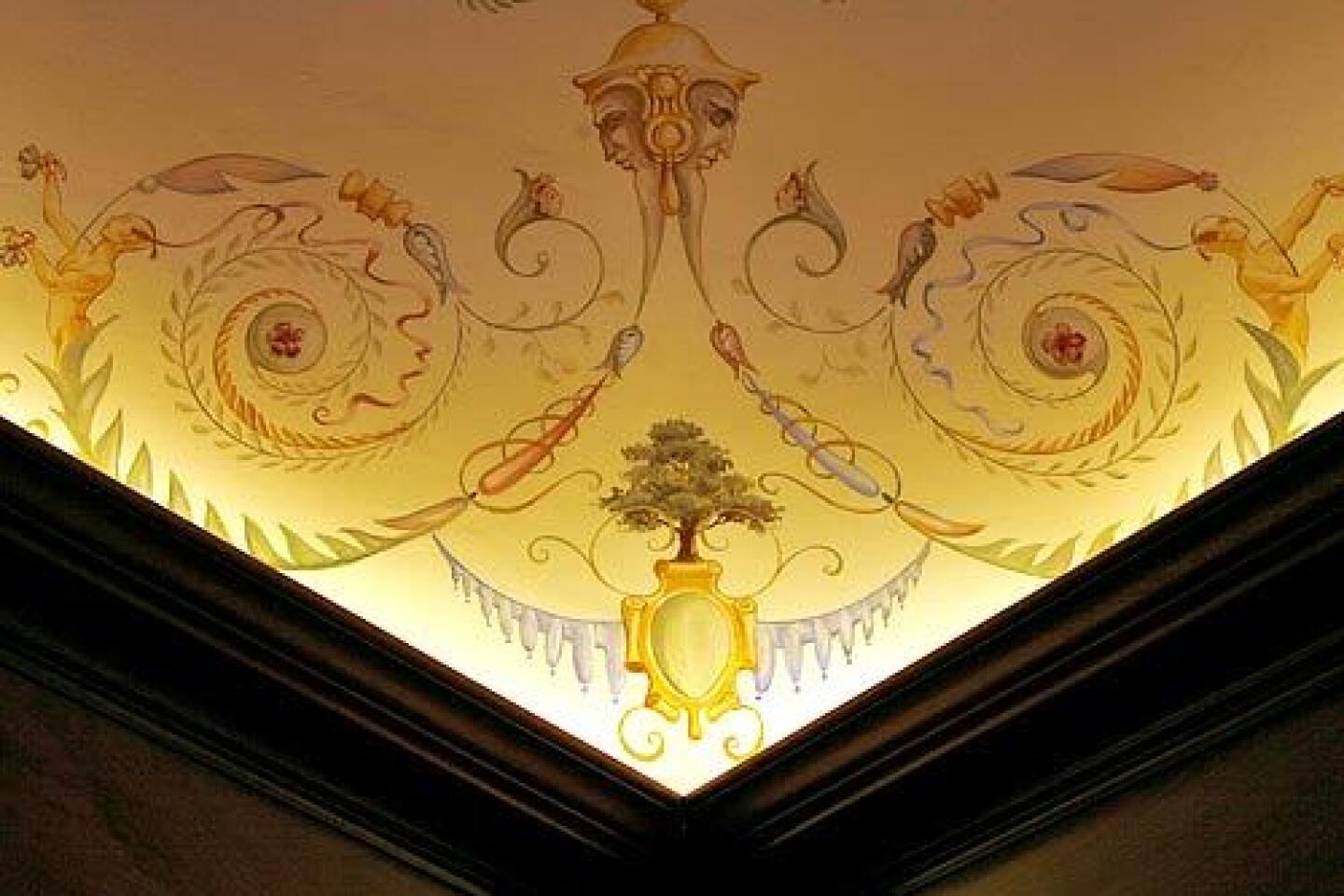

Many of their residential projects are lost — diminished by time or demolished by the ignorant. A stunning example remains at the Cedars, the Beaux Arts-meets-German hunting lodge built in 1926 in Los Feliz. The home was built by Maurice Tourneur, the French director of “The Poor Little Rich Girl” with Mary Pickford, according to Fred Massarik, the UCLA professor emeritus who owned the property for 35 years. Tourneur brought in movie company technicians by the dozens to create intricately painted ceilings, figurative studies and gold leafing.

“The one person who was definitely involved in creating the murals was Mack Harris,” he says, citing the late painter who helped shape an array of rococo finishes, including playful love scenes on the dining room ceiling and printed phrases in the original master bedroom, including, “Never take advice from a woman in difficult times.”

It’s no wonder the mansion has drawn creative spirits — rockers Jimi Hendrix, Lou Reed and Arthur Lee, and actor Dennis Hopper. Fashion designer Sue Wong purchased the home in 2005 and brought in a mural conservationist to “brighten them up.” She says the extraordinary richness of the interior inspires her work.

“I’m a detailist,” Wong says. “So this is a house that’s very appropriate to me because of what I do.”

*

WONG would have been right at home among Hollywood’s early elite, many of whom were besotted with all that is rich, grand and sensuous. When Cary Grant moved into Norma Talmadge’s Santa Monica beach house in 1935, he tried to re-create Paris’ famed Maxim restaurant in his dining room and bar, complete with exquisitely hand-painted murals. “If I can’t go to Paris,” he said, “Paris must come to me.”

In the 1930s, filmmaker Dudley Murphy offered an exiled David Alfaro Siqueiros sanctuary in Hollywood, and in return Murphy received a hand-painted fresco for his Pacific Palisades backyard. Alfredo Ramos Martinez, director of Mexico’s National Academy of Fine Arts in the 1920s, painted murals and commissions for screenwriter Jo Swerling, costume designer Edith Head and actress Beulah Bondi.

“Martinez’s daughter had a spinal problem,” says Nathan Zakheim, a leading restoration expert. “He went around to different doctors in Beverly Hills, often painting frescoes in their homes in exchange for medical treatments,” says Zakheim, who relocated one piece from a home on Rodeo Drive not long ago.

Ramos Martinez’s 45-foot-long mural “El Dia del Mercado,” painted in 1938 for a Coronado restaurant and restored by Zakheim in the early 1990s, was eventually split into sections, one of which went to producer Joel Silver and is displayed in his Brentwood home.

“They’re fairly rare,” Leslie Rainer, senior project specialist at the Getty Conservation Institute, says of such pieces. “But they’re also very, very important, especially some of the great murals of the 1930s by the Mexican muralists, who were essential to the entire movement.”

*

THESE days, the rise in commissioned artworks includes major artists as well as established names. Until his death this year, New York-based Sol LeWitt was perhaps the best-known artist to work with walls, ceilings and floors. He would come up with a design for a home — about 1,200 during his career — and then allow the collector, with the help of LeWitt’s minions, to apply ink, pencil or tempera directly to the wall.

LeWitt’s work remains in the upper echelon of home commissions; two of his conceptual pieces recently sold at auction for about $150,000. But collectors have other options. Young contemporary artists Barry McGee and Trenton Doyle Hancock have been known to add graffiti-style flourishes such as cartoon imagery and text to their residential commissions. San Francisco-based Waterston prefers to work in a more somber mode with organic shapes awash in a netherworld of bubbles, branches and sunrays created on canvas off-site, then installed on walls.

Interior designer Molly Luetkemeyer commissioned Jeff Robinson to paint a flowering quince tree, whose distinctly mod form climbs from the living room wall onto the ceiling of her former L.A. apartment, now occupied by Kate Schintzis, a designer in Luetkemeyer’s studio.

“I love them,” says Luetkemeyer, who also has hired Michaela Daly and Karen Sikie to punctuate rooms with site-specific artworks. “They’re incredibly energizing. You can add this one, beautiful, dramatic gesture which completely activates the space, and it allows you to keep everything else fairly neutral.”

New York-based artist Nancy Lorenz, on the other hand, tends to create not just a single gesture but rather huge spans of color, which she augments with delicate brush strokes, gold leaf and mother of pearl. The Beverly Hilton hotel owns a 60-foot wall piece by Lorenz. Cindy Crawford, producer Joe Roth and former Bond girl Lois Chiles are also clients.

“I really love the scale,” says Lorenz, who often works with interior designer Michael Smith. “I love the sensation of walking along a really large painting.”

Lorenz and figurative painter Matthew Benedict were commissioned to bring a dash of Hollywood opulence to the Laurel Canyon home of interior designer William Sofield, who oversees the look of Gucci’s retail spaces worldwide. The result is a stately abode filled with Lorenz’s gestural, mother-of-pearl wall pieces in the living and dining areas, as well as Benedict’s evocative images of vintage Americana on various doors and hallways.

The house once belonged to Douglas Fairbanks and served as the location for United Artists’ inception, Sofield says. “We deliberately set out to evoke that era without trying to copy it,” he says. “So I feel that the artwork is very much a part of the house.”

That enthusiasm is echoed by the likes of restoration expert Zakheim.

“There’s something about being in the presence of something that is not only the result of extraordinary craftsmanship, but the result of something that takes a long time to do,” Zakheim says. “Because it gives you something back when you are in its presence. You’re looking at something that is full.”

And for homeowners like Midler, the effect goes beyond decoration to the essence of home.

“I love it and can’t imagine ever selling it because it is such a personal expression,” the entertainer says of her Beverly Hills house, which is filled with Kintisch’s wall paintings.

“She is a fine artist doing home decorating, and the results are not just beautiful but wonderful to live with. Her walls glow, and people are always happy to be in those rooms. Call me crazy, but that’s the truth.”

*

home@latimes.com

*(INFOBOX BELOW)

What makes a fresco

“Fresco” refers to the technique of applying pigment to wet plaster. “The depth of the pigment gives it an extraordinarily luminous quality,” conservator Nathan Zakheim says. Frescoes tend to last longer and retain their vibrancy better than some other techniques, but they can be expensive — upward of $25,000 for a small wall. They also can take months to complete, finished bit by precious bit. The technique is employed by California artists such as Ian Hardwick, iLia Anossov and Kelly Holden. “It’s historical art that didn’t exist in this country,” says Holden, who studied classic methods in Italy. “People find it intriguing because it’s so old and there’s beautiful history behind it.” Here, a brief look at Holden’s process:

**

More photos on the Web

For additional pictures of murals in Southern California homes, modern and traditional, look for the Home section’s photo gallery at latimes.com/home.