A most personal gallery

He seems like just the kind of guy you’d expect to be a success in the television industry. Brusque-yet-polished New York manners, semi-casual dress, dry wit and enough self-deprecation to let you know right away there’s a lot more intellect beyond the first impression. Dean Valentine, in other words, isn’t immediately surprising when he greets you with a friendly smile. At 48, he’s a longtime TV mogul who most recently has been spending the bulk of his time developing a family entertainment company. So when Valentine shakes your hand outside his Colonial-style Beverly Hills house, everything about him appears to make sense.

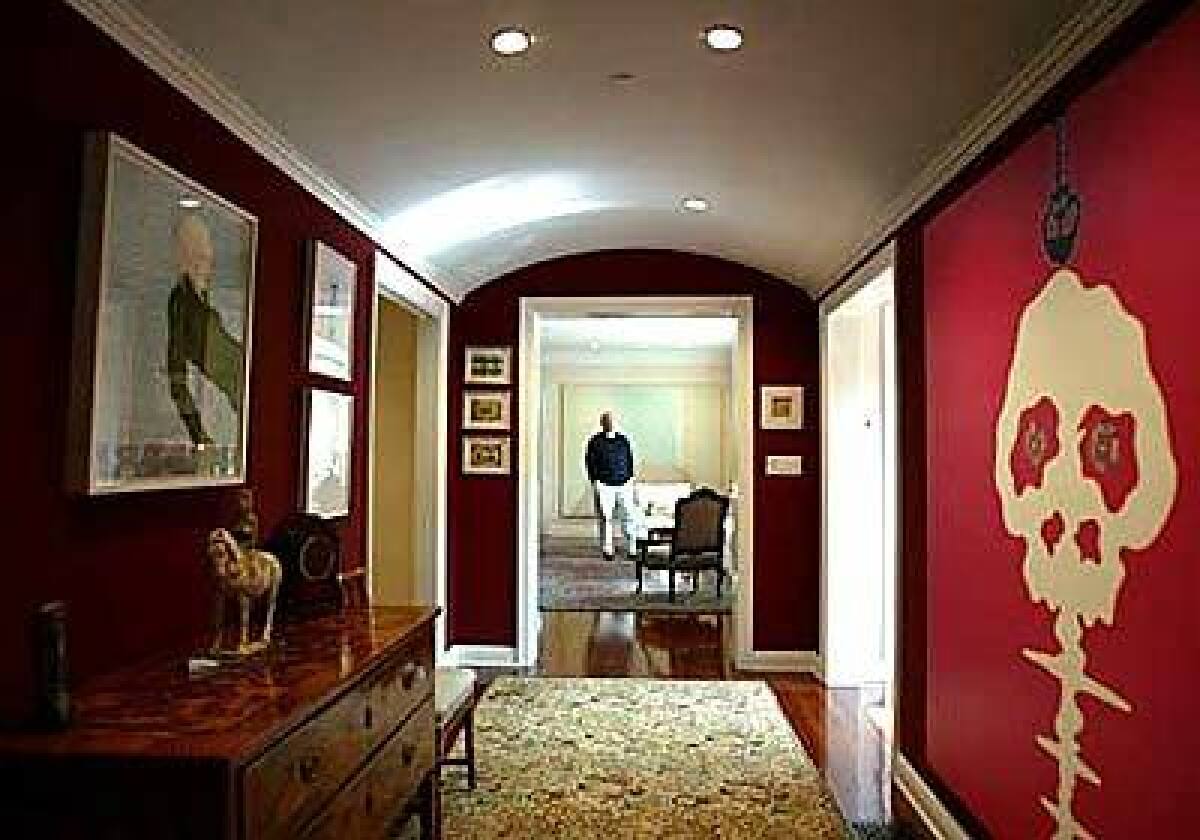

Until you walk in his front door.

Right off the bat there’s the huge cartoon-like image of a skeleton head, set against a fluorescent-pink background — a painting by the Japanese artist Takashi Murakami, whose work was recently featured in the “Superflat” exhibition by L.A.’s Museum of Contemporary Art. There’s also a small drawing done largely in Vaseline by Matthew Barney, an artist whose obsessive visions are currently the subject of a retrospective at the Guggenheim in New York. And there’s a series of works-on-paper by the Mexican-born, New York-based sculptor Gabriel Orozco, who also recently had a show at MOCA, as well as a much-layered drawing by Gregor Schneider, a German artist.

A very different Dean Valentine is behind all of this.

Add to this exuberant cacophony an Italian inlaid-wood commode, a Biedermeier chair and a colorful needlepoint rug, and you start to get the picture of a man who trades in adventure and powerful statements, and yet likes the comforts of a home. And that’s just the front hall.

A former head of Walt Disney Television, Valentine was, until about 16 months ago, president for four years of UPN, a network best known for showing wrestling. In the last five or so years, Valentine has also become known as L.A.’s strongest advocate for emerging young artists, particularly — though not exclusively — those living and working here, and there is much evidence of that in his home. He shares this sprawling house, built in 1939 by architect Paul Williams, with his wife, film producer and former ABC-TV executive Amy Adelson, and their two small children.

They have filled it with a mix of beautifully tasteful yet mostly conventional antique furnishings — chosen by Adelson — and art that is completely the opposite — chosen by Valentine. The juxtaposition of old and new, hot and even hotter in a sprawling house that looks like anything but a museum reveals the private side of Valentine — a man who in just the last decade fell in love with art.

The house at one time belonged to Ernie Kovacs and has been added onto frequently over the years; it is now stuffed top to bottom with paintings, drawings and some sculpture, although the latter have been sharply reduced in number for safety reasons since the kids became toddlers. Many styles of work bump up against one another, but most of it is aggressively narrative, and as you walk through the house it’s impossible not to stop constantly to figure out what it’s all about. As he guides a visitor around the eight or so spacious rooms that display the collection, Valentine stops to point out the details of each of the 60 or so pieces installed here and often starts off with “This is one of my favorites.” His opinions are strong, his knowledge deep and his enthusiasm unabashed. “I tend to like things that have great intellectual force and great physical presence at the same time,” he says by way of drawing it all together. “There’s a level of Romanticism in the work that I like. All the best art deals with issues of life and longing and beauty and truth.”

You can see what he means in the paintings by New York-based John Currin, which are sprinkled throughout the house. A painting in the living room of a woman seated on a grassy hill evokes thoughts of loneliness and penetrating yearning. In the den another Currin, a life-sized image of a young female titled “Carol” is a classically dissonant image of seduction and vulnerability.

There’s also the chess set by Orozco in front of the hearth in the living room titled “Horses Running Endlessly,” where the board is much larger than the norm and every delicately crafted wooden piece is a knight. The work’s scattershot arrangement is both silent and chaotic, as if all those horse heads are perched to begin to move at any second. Valentine says his 17-month-old son used to love to sweep all the pieces off the board, but has learned that’s not OK.

There’s sweetness and humanity to much of the work too. Andrea Zittel, based in New York and Joshua Tree, conceived a series of “escape vehicles” that would look like mini Airstreams on the outside, with custom interiors to reflect the buyer’s yearnings. Valentine came into the project with some trepidation, having admired Zittel’s work but not knowing her personally.

“It was not like buying a painting,” he says. “It was like buying into a relationship.” Because of his fascination with Joseph Cornell, he asked Zittel to make his box a life-sized space that echoes Cornell’s work. The result includes, in human scale, all the best of Cornell, including a robe based on Vermeer’s astronomer. “I like that it’s rickety and very 19th century,” Valentine says, “and it has room for a bottle of bourbon, which is important to me.”

This piece, installed on a second-floor balcony overlooking the library, also demonstrates Valentine’s commitment to ambitious work, whatever its demands on his home. Adelson recalls the agony of its installation. She was pregnant at the time with their first child and watched with great fear as the life-sized mobile-home-style structure was lifted by crane through a second-story window. Her fear was that her house — let alone the artwork — would be damaged. In the end, everything survived intact, and Adelson says she loves Zittel’s piece. “It’s so personal, very much a reflection of Dean as well as Cornell, and I love Cornell.” Both Valentine and their 3-year-old daughter love it, too, and both have on occasion spent time sitting inside the piece.

In the process of his artistic self-education, Valentine has become focused and opinionated, and he has a tendency to get heated up when talking about recent art’s intellectual territory. “We live in such a media-saturated culture,” says this media mogul, fully recognizing the irony. “And for the last 10 to 15 years, the conversation’s all been about that. Painting’s been based on photographic images; and the truth is, that is a thin diet for artists as well as for citizens. Some greater authenticity had to be found, and it is found in craft, the ability to make beautiful things connected with the tradition of art. As I look around at a lot of the work I have here, that seems to be one of the threads of it.”

It’s a touching statement from a man whose business is characterized by cut-throat deals, but it also is not entirely inconsistent for someone who lived through an always heated and often ugly public debate when he insisted that the coming-out show of “Ellen,” a personal revelation for comedian Ellen DeGeneres, needed to be aired. TV, for Valentine, hasn’t all been sports or “Aladdin” follow-ups. And unlike some in the trade who take every opportunity to disparage their medium, Valentine is also clearly comfortable living at once surrounded by very ambitious art that addresses a specific inner circle while working in a world trying to appeal to the masses.

“You don’t have to oversimplify people into stereotypes,” he says. “I genuinely love wrestling. I grew up watching wrestling with my grandmother when I was a kid. We always think, ‘Oh, a guy who collects art and reads can’t also like wrestling and TV,’ but that wasn’t the case. I loved television and I still do.”

But increasingly, his art is also making a name for him. He’s been frequently cited as one of the top collectors in America, and he serves on the power-list board of MOCA, where he chaired the acquisitions committee for four years. He owns far more works of art than he can show in his home, most of them in storage, many out on loan to museum exhibitions.

Among Valentine’s greatest thrills is catching stars before they begin to rise. Artists’ names like Currin, L.A. photographer Amy Adler, San Francisco installation artist Barry McGee, German painter Dirk Skreber or Japanese multimedia artist Murakami may not yet have much currency to general audiences, but in the art world they are among the ones to watch, and Valentine owns work by all of them. Buying first, when there’s no buzz, has been an act of faith for Valentine, and there have been plenty of mistakes, but he can live with that. The payoff comes not just from seeing value rise, but having his instincts validated. To that end, he actively advocates for artists whose work he likes, befriending some, bringing other collectors and dealers to see their work, and using his influence to help them make deals.

“He was my first experience with a collector who wasn’t just interested in pretty things,” says painter Mark Grotjean, who met Valentine when he was running a small gallery with some other artist friends, all of them freshly out of art school. Valentine paid them serious attention, and bought their work. “When that happened, I was working for $7 an hour at an art store. It really made a difference,” Grotjean says.

Valentine has also earned the respect of the professionals: “For every moment, there always seems to be someone who’s out there collecting at the beginning,” says Paul Schimmel, MOCA’s chief curator, who has worked closely with Valentine and calls him a friend. “But what’s most important about Dean is his promotional zeal,” Schimmel says. “He’s out in the studios as much as any curator or critic.”

To understand Valentine’s life and his love for art, you have to know that he is very much a family man who for the last 15 years has shared his life with Adelson, whom he married in 1997. While the art came into their lives long after they met, Adelson says she has come to love and respect his newfound addiction, even while it wasn’t her choice.

He began collecting in 1994, when his father was critically ill and he had moved temporarily to New York to be with him. Valentine needed distraction, and he found himself haunting the art galleries for the first time in his life. Some of his first purchases were reflective of his concern with mortality at that moment, and not many of those remain among his holdings. But the realization that anyone can own an art object — that they’re not just meant for museums — was deeply liberating.

“I believe there is a collector’s gene — and Dean has it,” Adelson says. Over their bed is a lovely small painting by Ed Ruscha titled “Stupid Idiot,” an interior with a TV set next to a picture window. “That sort of says it all,” says Valentine. “Which one are you going to look at?”

Valentine was born in 1954, in Bucharest, Romania. His family immigrated to France in 1960. A year and a half later, they landed in St. Paul, Minn., placed there by their sponsoring agency, the Hebrew Immigration Society. Not long after, they moved again, this time to Queens, N.Y., and they settled there permanently. The family didn’t have much money, but Valentine grew to love TV, and the culture of New York provided him with an education in theater and museums.

While a student majoring in English at the University of Chicago, he landed a job at Poetry magazine, which proved considerably more prestigious than lucrative. He also became a freelance journalist, writing theater reviews “because it was a great way to get great tickets for dates for free,” a calling he continued when he moved back to New York after graduation. He also worked for a variety of small magazines, then went on to Saturday Review and eventually was articles editor for Life magazine, from 1981 to ’83. While at Life, he played softball on the weekends, and in a stroke of luck met Brandon Tartikoff, president of NBC, on the ball field. Next thing he knew, Valentine was hired as director of comedy development at NBC. His success there led him to Disney, where he quickly rose through the TV ranks.

When he moved to UPN to run the network, it was a significant step, moving from the production side of the business to become a program buyer. And he didn’t completely take to it. He departed in January 2002 with an unnamed but reportedly significant settlement after suing Viacom for $22 million in bonuses he said was owed to him under the terms of his original contract. During his tenure, Valentine did engineer a bold move by bringing “Buffy the Vampire Slayer” to the network from its principal rival, the WB, and helped launch the latest addition to the “Star Trek” franchise with “Enterprise.”

Now, he’s got time to develop new projects, and, he says, less time for the art. “I think of myself as a media entrepreneur, and my wife thinks of me as unemployed,” he jokes. He claims he’s found himself working harder now than ever before. “And as my kids have started having language and ideas, I’ve had even less time.” Still, he religiously spends about four hours every Saturday going to galleries and studios, looking.

“You have to make time, just as you do for your wife and children. It’s a priority in my life. It’s something I do.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.