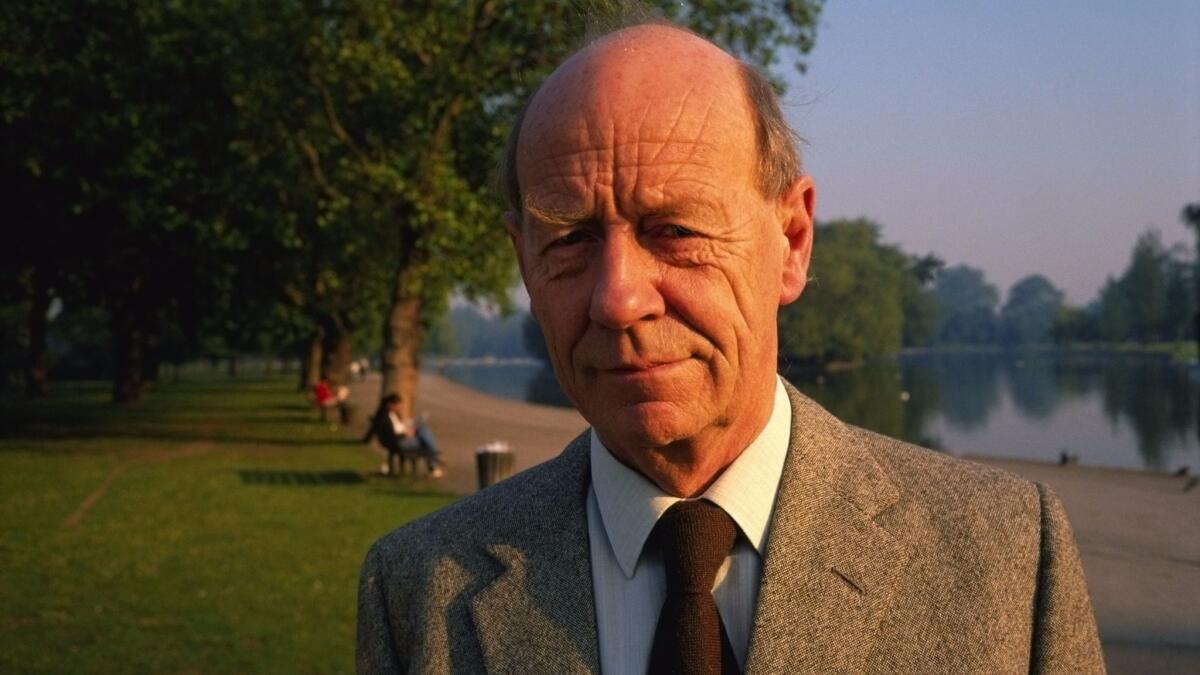

William Trevor explored the fictional possibilities of every type of person but himself

If you have been devotedly reading William Trevor over the past several decades, there’s a good chance you never learned much about William Trevor. This is because Trevor, like many great writers, explored the fictional possibilities of almost every type of person but himself. In 11 short-story collections published over 50 years, he depicted an almost unencompassable variety of all-too-human characters: yearning Irish farmgirls, divorced dads, cheating spouses, love-shy middle-aged bachelors, bereft and dazed widowers, merciless Victorian-era butlers, alcoholic priests and foolish-love-lorn elderly professors. Yet he never wrote about anyone who remotely resembled William Trevor: a steady and quietly productive, Irish-expat short-story writer who immigrated to England in the ’50s, won some literary awards, and lived in the isolated Devon countryside long enough to complete nearly 20 memorable novels and novellas, and 100-plus even-more memorable short stories. “I have no interest in myself,” Trevor once unsurprisingly confessed. But judging from his stories, he possessed a bountiful interest in everybody else.

Trevor, who died Sunday at age 88, was born in County Cork in 1928. He benefited from early failures: He was a schoolteacher, a sculptor (he later claimed his work simply “didn’t have something”) and an advertising copywriter (“I was extremely bad.”) It is hard to underestimate the value of failure on good writers, and in Trevor’s case it taught him the necessary stuff: that he couldn’t do anything but write; and that he felt a natural affinity for the sort of “unheroic” characters who populate good stories. “Heroes don’t really belong in short stories,” he once said, echoing one of his major influences, Frank O’Connor. “I find the unheroic side of people much richer and more entertaining than black-and-white success.”

Trevor went on to explore, and elevate, many laudably unheroic natures. In his most famous story, “The Ballroom of Romance,” 36-year-old Bridie rides her bike every week to a shabby local dance hall in search of romance, and eventually settles for much less. And in “A Complicated Story,” a shy middle-aged man is enlisted by a neighbor to help move her lover’s dead body before the husband gets home — only to find, once he breaks out of his shell, that the lover isn’t actually dead (only resting); and so he marches dutifully back to his previous state of not being needed.

The “significant event” in a typical Trevor story often sends its central character back to the uneventful life that they’re already living. And even when these fictional lives are far from happy, the sad, funny stories that develop are always beautiful, satisfying and perfectly formed.

“I have no messages or anything like that,” Trevor once said; “I have no philosophy and I don’t impose on my characters anything more than the predicament they find themselves in. That seems to me to be quite enough to go along with.”

In many ways, Trevor’s temperament was better suited to short stories than to longer forms; and while he wrote many good novels, he referred to them (quite accurately) as “linked-up short stories.” (“I’m a short-story writer, really, who happens to write novels. Not the other way around.”) Even his best novels, such as “Felicia’s Journey” (filmed by Atom Egoyan in 1999) or “The Story of Lucy Gault” (a decades-spanning tale of a child abandoned by her parents), lack the intensity and conviction of his 100-plus short stories. Perhaps this is because the predicaments that define Trevor’s characters are never large enough to sustain novels, even when his relatively “small” characters are interesting enough to deserve them.

For Trevor, each story was an experiment in form. Every story he wrote took the time it needed to establish a world, a convincing human life (or several), and a satisfying sense of completeness — just before shutting the door on its readers, and its vision of the world, forever. And since each story is satisfying and complete in itself, most good readers can’t simply finish one and rush off onto another. “If the novel is like an intricate Renaissance painting,” Trevor told the Paris Review, “the short story is an impressionist painting. It should be an explosion of truth. Its strength lies in what it leaves out just as much as what it puts in, if not more. It is concerned with the total exclusion of meaninglessness. Life, on the other hand, is meaningless most of the time. The novel imitates life, where the short story is bony, and cannot wander. It is essential art.”

Unfortunately, readers aren’t easily able to read a writer like Trevor in the venue best suited to his talents — the single-author collection. Usually, short stories are either jammed together in worthy, elbow-straining textbooks and anthologies defined by “greatness” or “Irishness” or “period,” or made to compete with novels as doorstopper-sized editions of “Complete Stories” (even as far back as 1993, Trevor’s collected stories were large and heavy enough to hold open several doors.) But stories aren’t enjoyable in proportion to the size and weight of the package that delivers them; if a good short-story writer teaches us anything, it is to accept the limitations of form.

To read a good single-author collection of stories — such as any one of the 11 unique and satisfying collections Trevor produced over his lifetime, including “The Ballroom of Romance” (1972), “Angels at the Ritz” (1975), “The Hill Bachelors” (2000) and “Cheating at Canasta” (2007) — requires far more time and concentration than any shaggy, Pulitzer-worthy novel; this is because each story in it is not an analysis or explanation of our world, but rather only a perfect expression of itself. As Trevor once explained, the only purpose in telling a story is “because it makes a good story. And you tell it, because that’s how you communicate.”

When I was growing up in California in the ’70s, there weren’t many good reasons for practicing the difficult (and continually pleasurable) art of writing short stories, but one of the best reasons was the work of William Trevor. Like most of my favorite story writers at the time — Richard Yates, Raymond Carver, Alice Munro, even Ray Bradbury and Thomas M. Disch — Trevor didn’t simply teach me the manifold possibilities of telling stories. He proved through performance — year after year and decade after decade — that a good writer could keep pulling a different rabbit out of the same hat again, and again, and again. He is one of the few short story writers who never let me down. He will be missed.

Bradfield’s most recent books are “Why I Hate Toni Morrison’s Beloved: Several Decades of Reading Unwisely” and a revised edition of his 1995 novel, with a new afterword, “Animal Planet.”

More to Read

Sign up for our Book Club newsletter

Get the latest news, events and more from the Los Angeles Times Book Club, and help us get L.A. reading and talking.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.