Jack Cole made Marilyn Monroe move

The first man to impersonate Marilyn Monroe may well have been her dance coach, Jack Cole. Anticipating the iconic Marilyn, he brought out her exceptional femininity through dance. Monroe copied him in return. A star was born.

Monroe’s six-movie collaboration with Cole began with 1953’s “Gentlemen Prefer Blondes,” the breakthrough film that made her a superstar. Yet the man behind the icon has been forgotten -- an odd missing puzzle piece in view of Monroe’s staying power.

Revelations about the pioneering jazz-dance choreographer’s influence on his talented pupil continue to surface in interviews, biographies, archival material and an upcoming Cole documentary. It all leads to a critical reassessment of an overlooked dance artist who lived and worked in Los Angeles for 33 years.

Coming 47 years after her death on Aug. 5, 1962, it also sheds new light on Monroe’s capacity to improve her craft. With other authority figures, Monroe could be vague and even rebellious. With Cole, a stern taskmaster who did not suffer fools, she buckled down.

A preeminent film choreographer when he joined Twentieth Century Fox to oversee “Gentlemen’s” musical numbers for director Howard Hawks, Cole came to Hollywood from the world of nightclubs and Broadway. His decade-long film portfolio included remarkable female solos: “Put the Blame on Mame” for Rita Hayworth in “Gilda” (1946); “No Talent Joe” for Betty Grable in “Meet Me After the Show” (1951) and “Beale Street Blues” for Mitzi Gaynor in “The I Don’t Care Girl.” (1953).

In “Gentlemen,” Cole connected the nondancer Monroe to her fulsome body, giving her the power of movement. But he went even further, injecting comic zing into her line readings and coaching her breathy song delivery. Forming a bond with the insecure actress, Cole helped solidify the dumb-blond persona she introduced in “Monkey Business,” “All About Eve” and “Love Happy.” In her much beefier role in “Gentlemen,” they perfected it, together.

Difficult people

Monroe famously drove entire movie sets crazy. Producers sweated her tardiness; she was a budgetary time bomb. Directors seethed when she consulted her private drama coach. Fellow actors stewed because her flubbed lines meant multiple takes. Tremulous, tearful meltdowns visited her regularly. She often hid in her dressing room, dreading the soundstage.

Cole was a known terror in the dance studio. An inveterate curser, he hurled invectives at even his most faithful followers. During one of his brutal technique classes, he dragged one girl by the hair across a sweat-stained floor while threatening to toss another out a second-story window. When a dancer fainted in rehearsal, others, afraid to stop, hopped awkwardly over her body. In his early years hoofing in nightclubs, he harangued bandleaders who didn’t swing and scolded chatting customers. Wearing harem pants and a bare chest, he chased one belligerent client down Wilshire Boulevard wielding a kitchen knife.

The pairing could have been a hellish match. And yet these two supremely flawed people collaborated productively over six films. Their heady first result, the“Diamonds Are a Girl’s Best Friend” dance sequence from “Gentlemen,” is a delicious confection, a piece of Hollywood perfection. Although covered in Cole’s fingerprints, many are unaware that the sequence even had a choreographer.

Snatching the plum role of Lorelei that Carol Channing originated on Broadway from Fox’s aging song-and-dance queen Betty Grable set the stakes high for Monroe. She knew her limitations. She understood the cruel microscope of the movie camera and had never been in a musical. Determined to succeed in “Gentlemen,” Monroe rehearsed relentlessly alongside genial costar Jane Russell.

“Marilyn and I had never danced before; we were a pair of klutzes,” Russell told Cole biographer Glenn Loney in Dance Magazine. “Jack was horrible to his own dancers, but with us, the two broads, he had the patience of Job. He would show us and show us and then turn us over to Gwen.” (Gwen Verdon, Cole’s protégée, was on the brink of Broadway fame as the high-kicking redhead dancer of “Can-Can.” Married to (and separated from) choreographer Bob Fosse, she died in 2000). Russell said she fled several sessions in exhaustion while Monroe begged Cole and Verdon to continue into the night.

“My mom liked both Marilyn and Jane,” remembers Verdon’s son, James Heneghan, 10 at the time. “But Marilyn especially displayed a tough work ethic that was a big deal with my mother.”

Molding Marilyn

Monroe’s relationship with Hawks had deteriorated after he directed her in “Monkey Business” in 1952. Renowned for mentoring actresses (notably Lauren Bacall), Hawks was a connoisseur of slender women. The Monroe aura eluded him. In his Hawks biography, Todd McCarthy writes that Hawks found her sexuality vulgar. Plus, her late arrival to work and reliance on her acting coach infuriated him. Only studio head Darryl Zanuck’s enthusiasm over early rushes kept Hawks from firing Monroe. It’s feasible that the legendary director’s anger drove the terrified actress toward Cole.

For “Diamonds,” Cole crafted Monroe a simple palette of bare-bones moves. He knew her bells and whistles would ramp it up. First, she’s whisked around the red-drenched stage (a Cole trademark) by a bevy of male dancers (another). On her own, she does little more than skip or walk, saucily shifting her weight at the hip. Adding new dimension, Cole micro-choreographs for the camera. Monroe purses her lips, winks, points a gloved finger, shrugs her shoulders and sensually touches herself. The effect is radiant and erotic. It’s eye candy.

In conversation with Annette Macdonald in “Jack Cole: Jazz,” a Timeline Films documentary that’s been delayed by lack of funding, Monroe’s vocal coach Hal Schaefer remembers Marilyn as a keen student. “Marilyn had fluidity, but she lacked strength and clean lines. Jack was brilliant in telling her what to do.

“He wanted her to make a move, and she put her arm out. It just kind of drifted. Jack said, ‘No, wait. Sharp, I want it sharp!’

“ ‘But Jack, I’m supposed to be a sex queen,’ she said.

“And he answered, ‘That’s not sexy. That’s like a limp fish. Put that arm out there, strong! That’s sexy! That’s life, that’s alive, that’s energy!’ ”

In his 1984 Cole biography, “Unsung Genius,” Loney quotes music arranger Peter Matz: “The persona Marilyn showed in her film musicals was Jack Cole. He grabbed on to something in her. She followed everything he gave her. Phrasing! The gestures, the walk. All of it!”

In fact, “Diamonds” belongs to Cole. He directed it. Feeling unqualified, Hawks opted out of “Gentlemen’s” musical numbers. Russell told McCarthy, “Hawks was not even there.” Verdon agreed, telling McCarthy, “Jack decided where the camera should be, setup by setup, in consultation with [director of photography] Harry Wild. He also synced camera angles with [editor] Hugh Fowler. Hawks stood by and let Jack do what he wanted.”

Cole used a heavy hand in reworking “Diamonds” from the Broadway version, Schaefer recalls: “The original concept for the number was way too square. Cole redid it in a sensual way for Marilyn. He told me, ‘I want to make it swing. I want to get it loose.’

“The part where she bumps and grinds, sensually naming famous jewelers, Tiffany’s, Cartier, Black Starr -- that’s not in the [Jules Styne/Leo Robin] original. That’s Jack’s material. He wrote it. Then he taught Marilyn how to move on it.”

The moves he made

Like Monroe the product of a fatherless home, the New Jersey-born Cole began his career with Ted Shawn and Ruth St. Denis’ Denishawn modern dance ensemble. Disenchanted with Denishawn’s pseudo-Orientalism, he studied India’s bharata natyam. In a moment of inspired genre-busting, Cole infused Indian dance into his jazz-based supper club act. The cool combination fit surprisingly well with postwar beatnik culture.

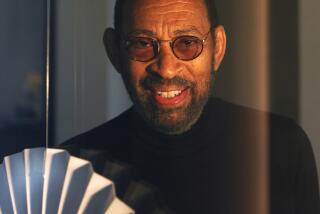

An odd-looking man with high cheekbones and one lopsided eye, this exotic creature dressed like an Indian swami garnered bookings at top nightclubs. He was a regular at New York’s Rainbow Room and bookings at Ciro’s and Slapsy Maxie brought him to Los Angeles. So did Hollywood.

In 1941, Cole and his dancers first appeared in “Moon Over Miami.” In 1946, after blessing the formerly shy Rita Hayworth with her sultry “Mame” number, she championed him at Columbia Pictures. (Betty Grable did the same at Fox.) For four years, Cole ran a resident dance group at Columbia, where innumerable dancers ruined their knees perfecting the master’s diabolical floor slides.

In 30-plus movies, many uncredited, Cole lighted a blowtorch under 1950s bombshells -- Grable, Hayworth, Bacall, Russell, Gaynor, Ann Miller, Lana Turner, Dolores Gray and Monroe. Fifties screen virgins like Doris Day are not on this list; Cole’s work sizzled with sex. Although he purported to loathe L.A. (keeping a Manhattan pied-à-terre for Broadway work), Cole’s primary residence was in the Hollywood Hills from 1943 until his death from cancer at 62 in 1974. In his last two years of life, he was a treasured UCLA dance instructor and a scholar with an impressive private dance library.

The partnership

During production planning for “Gentlemen” in March 1952, word of Monroe’s nude calendar photos from the late ‘40s exploded in the media. Darryl Zanuck reacted unambiguously in a memo: “Cover her up.” Travilla, Monroe’s costumer, ditched his original design for “Diamonds” -- a low-cut rhinestone burlesque bikini worn over a giant fishnet body stocking (photos show Monroe posing uneasily in it).

Replacing this cheesy look was an astonishingly sophisticated form-fitting fuchsia evening gown. Cole, a costume maven, may have influenced it. The classy outfit bears a striking similarity to Hayworth’s get-up in “Mame” -- also a strapless evening gown worn with opera gloves designed by Jean-Louis.

(Travilla said in a 1981 L.A. Times fashion column that he lined the hot-pink peau de soie tube with felt to keep all of Monroe’s parts moving in one direction. “But underneath that, Marilyn wore Marilyn,” he added slyly.)

In July 1953, “Gentlemen Prefer Blondes” opened to glowing reviews, particularly for Monroe. The Hollywood Reporter praised her “wiggle terps.” Newsweek noted that the “camera itself can be the most expressive of dancers” while leaking Monroe’s secret, which was “to avoid repose, always keeping lips, hips or some other department at least slightly in motion.” Time’s critic wrote, “she dances, or rather undulates all over, fluttering the heaviest eyelids in show business.”

In her difficult 1954 contract renegotiation with Fox, Monroe demanded the right to approve her drama coach, Natasha Lytess, and her choreographer, Jack Cole. Monroe and Cole worked again in “River of No Return” and “There’s No Business like Show Business” (1954), “Bus Stop” (1956) and “Some Like It Hot” (1959).

In the end, Monroe drove Cole crazy too. During the 10-week rehearsal period for “Let’s Make Love” (1960), Cole fumed in a dance studio with Monroe showing up late, if at all. The resulting mess of “My Heart Belongs to Daddy” ranks many notches below the sparkling perfection of “Diamonds.”

But they were friends. By 1962, Monroe included Cole in her close coterie, and they were telephone buddies. She leaned on him, among others, hard in the end.

Jack Cole took a gorgeous woman at the height of her physical beauty and gave her the ability to communicate with her body, a means of expression beyond cinema’s main instruments of face and voice. He expanded her repertoire as a film artist. It was an immense gift, and Marilyn Monroe knew it.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.