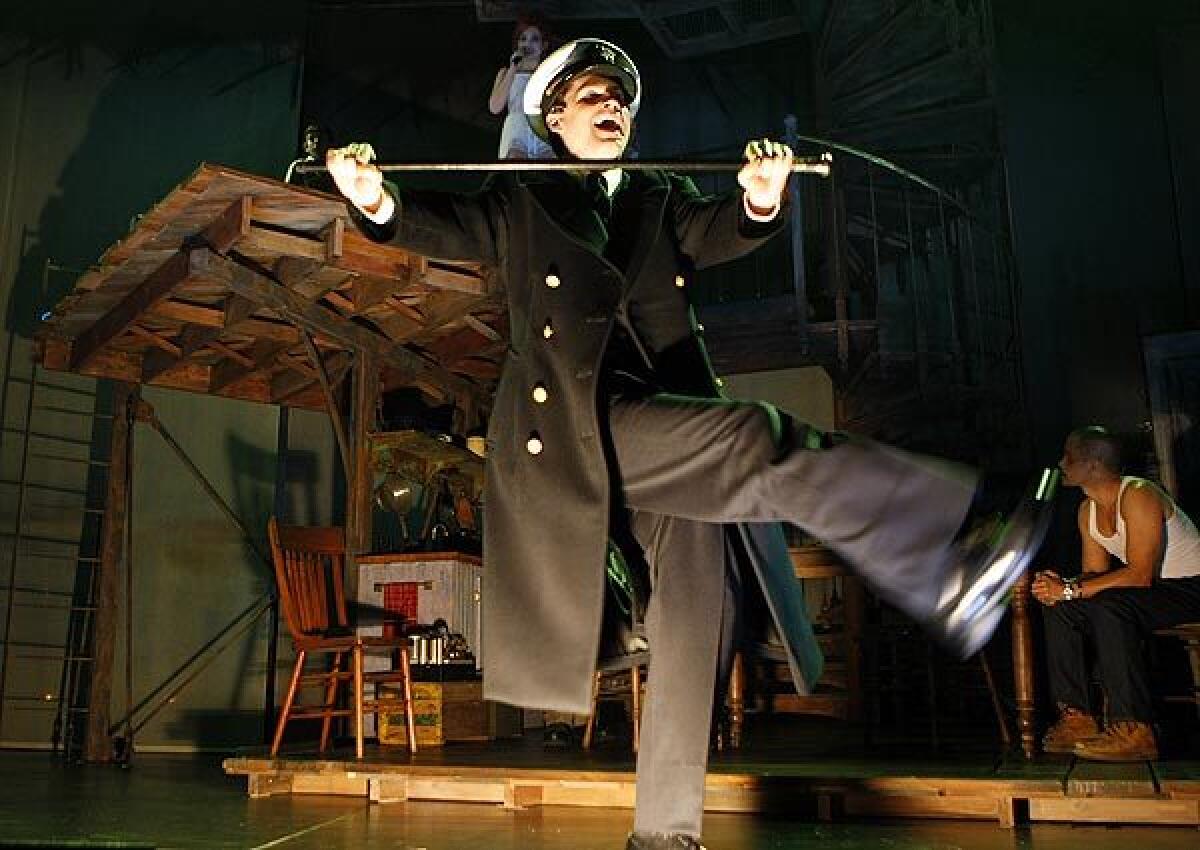

Duncan Sheik enters the ‘Whisper House’

Duncan Sheik is a skeptic of the supernatural -- “I completely don’t believe in ghosts,” the singer-songwriter says. Yet if his new musical “Whisper House” is to succeed in its world premiere Thursday at the Old Globe Theatre, audiences -- not to mention some of the musical’s characters -- will need to have faith in things that go bump in the night.

The musical unfolds in distinct but concurrent realms: the living (five inhabitants of a coastal Maine town) and the dead (two singing ghosts, and their seven-piece backup band). And there are three separate “Whisper House” time periods: The ghosts last drew breath in the early 20th century, the people in Maine are living in the 1940s, and the musicians could have been playing a gig last night at Club Nokia. If the show comes together, none of that should matter.

Recent history stands to benefit “Whisper House.” “Spring Awakening,” the 2006 theatrical love child of Frank Wedekind’s late 19th century coming-of-age play and Sheik’s modern ballads, not only swept the Tonys (eight wins, including best musical) but also proved that the sum of a classic text and contemporary melodies can actually be much greater than its outwardly dissonant parts.

“Whisper House” loosely follows that mash-up model, yet with a novel twist: The five “Whisper House” protagonists don’t break into song. Instead, the new musical’s choral complement is delivered by rock-and-rolling ghosts, who wander in and out of the action like ethereal intruders.

“The question now is how is this going to read?” Sheik says between rehearsals in San Diego. “How funny is or isn’t it going to be? That’s a total mystery to me. I just hope it’s going to work.”

What grows from fear

The new production, with music and lyrics by Sheik and a book and lyrics by Kyle Jarrow, may unfold during World War II but owes its thematic inspiration to modern conflict and the paranoia it can incite. When the creative team assembled for the show’s first read-through in mid-December, Jarrow stood before the cast and crew to say he saw “Whisper House” as being as much about orange threat-level alerts as anything else.

“I first started writing this in the heat of the Iraq war -- that fear is something that guides a lot of life, that there is all this stuff telling us to be afraid,” said Jarrow, whose playwriting credits include “A Very Merry Unauthorized Children’s Scientology Pageant” and “Armless.” “How do you process fear and not let it control your life? That’s one of the biggest questions of modern living.”

Modern living isn’t intrinsic to “Whisper House,” as the story unfolds in early 1942. Christopher (Eric Brent Zutty) is an 11-year-old boy whose pilot father was killed by the Japanese; his mother, devastated by grief, suffers a nervous breakdown. Christopher is accordingly dispatched to a Maine lighthouse run by his spinster aunt, Lilly ( Mare Winningham).

Lilly is assisted in her coastal endeavors by Yasuhiro (Arthur Acuña), a Japanese American of whom Christopher immediately becomes suspicious. Christopher’s anxiety grows stronger as the show progresses, and he sees signs of treachery in what might be benign acts.

At the same time, Lilly reconsiders where her personal loyalties lie: to her cosseted, emotionally protected life or to those people around her who need (like a lighthouse, put another way) a beacon of guidance and protection.

As the threat of U-boat attacks intrudes on the ordinary isolation of the “Whisper House” lighthouse, so, too, do the show’s ghosts. The shadowy musicians -- the wraithlike remains of a band whose steamer was dashed on nearby rocks in 1912 -- are led by two vocalists (David Poe and Holly Brook) who not only offer commentary on the on-stage action but also, like contemporary sirens belting out pop songs, try to lure the lighthouse’s inhabitants to their own personal shipwrecks -- even suicide.

As the musical’s opening song, the moody ballad “Better off Dead,” has it:

Release your heavy heart

Rest your weary head

When all the world’s at war

It’s better to be dead

“Whisper House” presents unconventional staging on a number of levels. In “Spring Awakening,” the songs by Sheik and Steven Sater served a different narrative purpose (articulating the characters’ inner lives) and were performed by the principal cast; as with most musicals, the songs gave way to dialogue (and vice versa) about every five minutes.

In “Whisper House,” the show unfolds like a traditional play for longer stretches -- the musical numbers are fewer (11 total, compared to “Spring Awakening’s” 20 tunes) and further between, with some dialogue scenes lasting more than 10 minutes. “In normal musical theater, that would be anathema,” Sheik says. “I was initially a little bit concerned about that. And the music is from a totally different reality from what’s happening on stage.”

At the same time, some of the “Whisper House” songs are performed as shadow plays in pantomimes projected on a translucent upstage screen, choreographed by Pilobolus Dance Theatre’s Matt Kent, who collaborated with Poe on the dance troupe’s recent “Shadowland” show.

What’s more, the rules for the interaction between the dead and the living aren’t always clear. Christopher can hear the ghosts’ music, but even though Poe’s crooning apparition blows out Yasuhiro’s Zippo while he’s trying to light a cigarette, it’s ambiguous who can (and can’t) discern the ghosts’ physical presence. What’s less vague is their role as they wander about the stage: They’re gumming up the works, stoking paranoia.

“No matter what you do,” the ghosts sing in the parable song “The Tale of Solomon Snell,” “you’ll never be safe.” Or, in what Sheik and Jarrow say is a parroting of statements from the George W. Bush administration in the song “We’re Here to Tell You”:

We’re here to tell you

That all of this is real

And if you’re terrified today

That’s how you’re supposed to feel (for real)

“The ghosts are meant to muck up the lives of the living characters” says the musical’s director, Peter Askin (“Sexaholix,” “Hedwig and the Angry Inch”). Adds Jarrow: “The more they can make the living people’s lives awful, the more their song ‘Better off Dead’ makes sense.”

The musical was originally commissioned by Connecticut’s Stamford Center for the Arts in 2007 with actor Keith Powell (“30 Rock”) set to direct, just as “Spring Awakening” was becoming a Broadway sensation. Sheik and Jarrow went off to write, knowing the songs would have to carry a narrative burden that the “Whisper House” book couldn’t shoulder on its own.

“These are characters who don’t talk about their feelings a lot,” Jarrow says. “But you need back story. You need exposition. And you don’t want to put that in the mouths of characters who wouldn’t say it.” But by the time the music and book were fleshed out, Stamford was on the ropes, eventually filing for bankruptcy.

Sheik, whose greatest pop hit was 1996’s “Barely Breathing,” already had recorded demo versions of the show’s songs, and Sony Music Entertainment decided to release the record as a concept album a year before the musical’s opening. “We didn’t know where the show would go up, but we knew it would go up somewhere,” Sheik says.

The album’s liner notes only hinted at what the underlying musical was really about. What’s more, the compositions and arrangements (a little guitar, some light percussion and a few horns) didn’t sound like Stephen Sondheim or Rodgers & Hammerstein. “It’s meant to be music you could hear in your car and you wouldn’t instantly know it’s musical theater,” Sheik says.

An early album release served another purpose. Sheik and Jarrow believed that introducing the music before the show’s premiere would familiarize some of the audience -- even if only a small fraction -- with “Whisper House’s” musical and dramatic lexis. “I think it’s really great when you know the music, to some extent, when you see a show,” Sheik says. It’s a formula that worked well with the Who’s “Tommy” and Tim Rice and Andrew Lloyd Webber’s “Jesus Christ Superstar,” both of which were first known as albums before they were seen as staged musicals.

If the music captures the imagination of people who don’t normally go to the theater (meaning anyone born after 1970), all the better. “To me, the tough thing about theater is: How do you get young kids to see it?” Jarrow says. “A lot of younger people will buy a concert ticket before they buy a theater ticket. And that’s a pity. I think the more ‘Whisper House’ sounds like a rock concert, the better.”

It’s the same kind of thinking that is guiding “American Idiot,” a new musical based on the songs of punk rockers Green Day that premiered last fall (under the direction of “Spring Awakening’s” Michael Mayer) at the Berkeley Repertory Theatre and will open on Broadway on April 20.

The Old Globe, which had been talking to Jarrow about another production, became the home for “Whisper House” after the Connecticut venue fell through. “We just think it’s different and special and fragile and unique,” Louis Spisto, the theater’s chief executive officer and executive producer, told the cast and crew at the musical’s first read-through. If the show succeeds in San Diego, a move to Broadway could be likely. “There are definitely parties interested in this,” Spisto said.

But before there’s any further talk of New York, Sheik, Jarrow, Askin and the show’s cast and creative team worked to make sure “Whisper House” feels like a cohesive whole, not so many competing parts.

“That’s what Duncan and I were most worried about,” Jarrow says. “We didn’t want it to be a play that pauses, and then there’s a rock concert.”

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.