Editorial: California needs to ensure that money aimed at low-income students actually gets to them

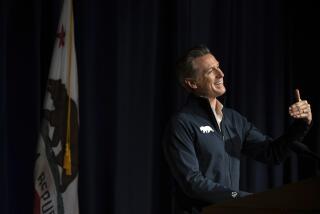

In the budget he released this week, Gov. Jerry Brown called for fully funding the Local Control Funding Formula, his landmark 2013 overhaul of education financing that was designed to direct substantial amounts of extra money to schools with high numbers of low-income students. More money has been going to the formula each year, and it’s great that now — two years sooner than expected — the governor wants to add $3 billion to the amount.

But the remaining challenge is to ensure that all that money goes to the students who need it most, and in ways that help narrow achievement gaps.

As clever as the funding formula is, it won’t be a success until the state puts some strings on it, rather than handing it out as a freebie for school districts.

Roll back several years to the recession we’d all like to forget. Brown cannily used the new funds that voters approved when they passed Proposition 30 for schools to revamp education funding. This would have been politically treacherous in earlier years because there would have been obvious winners and losers; some schools would have had to give up money so that others could have more. During the recession, though, most schools already had been losing money, and with the new tax money, they were all about to get more.

In his mission to give more authority to local districts, Brown placed few restrictions on how the money was to be spent.

Brown’s clever idea was that in a year when everyone was getting a bump, it would be easier to give still more to schools with heavier proportions of low-income students or students in foster care or still struggling to learn English.

This replaced a system that had funded schools at different levels based on — well, there were very few in the state who understood the complex formulas. Sometimes it was a matter of whether the school district was in a largely agricultural area back when Proposition 13 passed in 1978. Yes, it was that strange and ridiculously complicated. Brown’s new formula brought simplicity, clarity and equity to school funding.

The problem is that in his mission to give more authority to local districts, Brown placed few restrictions on how the money was to be spent and required no real accountability for ensuring that it was accomplishing its goals. The state laid down only one overriding rule: The money had to be used for the benefit of the students who bring in the extra funding.

That sounds sensible enough. But what exactly does it mean? Not that the state needs to or should lay down a complex set of rules that stifle local creativity, but at least there should have been some guidelines, such as: no using the money to fund unnecessary raises and growing retirement packages for employees. There should be some evidence that the expenditures are not being spent on business as usual, but will mainly benefit disadvantaged students. Already, a couple of lawsuits have been brought against school districts, including Los Angeles Unified, claiming that money was misspent under the terms of the law. The district settled.

So far, there’s little evidence that the extra funding has made a difference for low-income students. Achievement gaps between white students and their black and Latino counterparts haven’t narrowed significantly statewide. Still, change takes time.

Strangely, for all its loosey-goosey approach, what the funding law does require are extensive plans from each school district about its educational plans, which has largely resulted in long, opaque documents that generally are seen by nobody but the county-level bureaucrats who are required to review them. The process is complex and a waste of time and money.

Some school districts have conscientiously ensured that the money goes to programs to benefit low-income students and those still learning English. Others haven’t.

It’s good to see Brown budgeting more money for students who have long attended schools with less experienced teachers and fewer course choices than their more affluent counterparts. And we don’t mean to suggest that the state should impose a rigid list of items on which school districts can and cannot spend the money. There might even be a few cases in which using some of the money for, say, teacher raises makes sense — but only for school districts than can show they can’t hire or retain enough teachers because their pay scale isn’t competitive enough to attract candidates.

Brown’s educational legacy should consist not just of extra funding for schools, but extra funding that is used wisely and on the students for whom it was meant. Unfortunately, it seems that any changes will depend on the next governor.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.