Editorial: Why replacing L.A. County’s health director won’t be easy

When Los Angeles County supervisors describe the kind of person they want for a top department post, they often say something along the lines of, “We want a Mitch Katz type.”

That certainly speaks volumes about Dr. Mitchell H. Katz, who on Friday told the supervisors he’d be leaving the county at the end of the year. His departure culminates a stunningly successful run as leader, first of the massive Department of Health Services and then of the new and even more massive county Health Agency, which takes in the formerly stand-alone departments of mental health and public health. Katz turned about a third of the county’s operation and budget into a nimble human services organization that not only runs hospitals and coordinates clinical care, but also provides housing for the homeless and diverts the addicted and mentally ill from jails to clinics.

The supervisors’ respect for Katz also says something important about them, and how they think and work. They like superstars — magic men and wonder women who can transform previously struggling bureaucracies with vision and an ability to inspire confidence. They like people who make them look good. And who wouldn’t?

The problem for Los Angeles County is that there is a limited supply of such people, and there are good reasons why they might not want to spend their entire careers here. That kind of talent often gravitates toward the private sector, where the money is better, the bureaucracy less stifling and the politics less baffling. For those who do choose government, come to L.A. and are successful, there are even bigger opportunities waiting in the wings — like New York, where Katz is headed next (although he made it clear that he was moving not only to switch agencies, but to be near his aging parents). Like free agents in baseball and certain corporate CEOs, top-tier leaders of local government agencies tend to stay mobile.

The bench of magic men and wonder women in L.A. County’s bureaucracy is not deep.

It used to be different. Through most of the 20th century, local government bureaucrats and administrators were generally home-grown public servants who had worked their way up to the top job, where they enjoyed civil service protection, never got fired, delivered solid if often uninspired service and stayed in place for decades.

By the 1990s, though, Los Angeles County and other local governments eliminated civil service protection for top managers in a quest for more creativity and responsiveness. Now department directors who lose the confidence of their elected bosses get fired. The best tend to work their magic for just a few years, then accept new opportunities elsewhere.

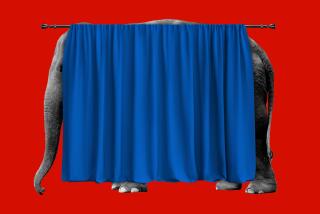

And after they leave, then what? The bench of magic men and wonder women is not deep. Does the departing superstar leave behind a trained and inspired band of lieutenants who can keep the program on track? Or at least a culture that can survive a lackluster successor? In the case of the L.A. County Health Agency, which Katz designed for himself to run, we can only hope that the structure fits his successor.

Whoever the supervisors choose will have to be not only smart and capable, but also adept at something that is unnecessary in San Francisco, New York or even L.A. City Hall, where one person — the mayor — is in charge: to thrive in L.A. County, Katz’s successor must count votes.

It’s a county quip that department leaders must be able to count to three, keeping the support and confidence of a voting majority of the five supervisors who oversee them. But, in fact, anything less than five is a signal of weakness to the workforce, the unions and would-be allies or opponents. It may portend a troubled tenure, marked by resistance from labor and micromanaging from the supervisors.

Sometimes the board works it out — at least temporarily. A year ago the supervisors split over who should lead the perpetually fraught Probation Department, but landed on the happy solution of making Terri McDonald the chief probation officer while putting Sheila Mitchell in charge of the Juvenile Division — an appointment that played to the particular strengths of both leaders.

Last week, though, when the board picked Bobby Cagle to lead the similarly troubled Department of Children and Family Services, the supervisors made it clear that their vote in closed session was 3-2. And they took the unusual step of publicly releasing the name of the runner-up candidate. That can’t help but leave social workers and their union wondering whether their new boss-to-be is skating on thin ice before he even shows up for his first day of work.

That dynamic is another reason it has been difficult to attract talent to L.A. County, and a reason why new leaders, new thinking and new department cultures can seem so ephemeral. Running a county department is hard. Retaining the trust and confidence of five sometimes squabbling supervisors is harder.

Follow the Opinion section on Twitter @latimesopinion and Facebook.

More to Read

A cure for the common opinion

Get thought-provoking perspectives with our weekly newsletter.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.