Through ‘Silence,’ Martin Scorsese examines his own spiritual journey

At a 1988 dinner following the premiere of Martin Scorsese’s controversial testament of faith, “The Last Temptation of Christ,” Paul Moore, then the Episcopal bishop of New York, told Scorsese about a book he should read. Within a day or two, Moore sent the filmmaker a copy of “Silence,” Shūsaku Endō’s novel about two Jesuit priests who travel to Japan in 1639 to find their mentor, a man rumored to have renounced his beliefs under torture.

When Scorsese began reading the novel a year later, he found he couldn’t shake the story of its conflicted main character, Father Sebastião Rodrigues, a man working through his own pride and doubts in his quest to serve his God. Scorsese came close to making “Silence” several times in the intervening decades. Now that he has, he views the finished film as a “stripping away of everything extraneous to get to the essence, the spiritual.”

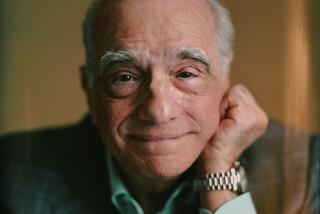

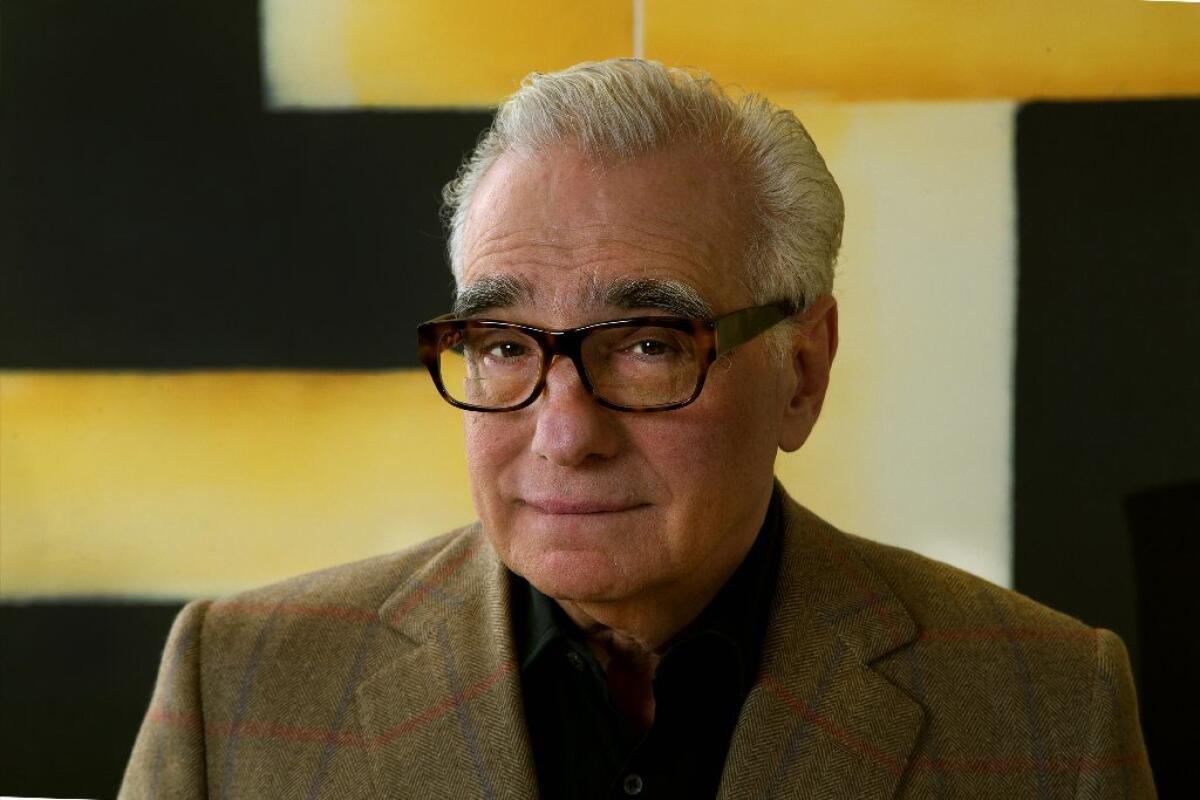

We sat down with the 74-year-old director to talk about that essence and what he calls the “never-ending pilgrimage” of making “Silence” and understanding the truth found in Endō’s cherished novel.

There’s a through line between “The Last Temptation of Christ” and “Silence.” Both movies raise questions about the foundations of faith and both speak to people who have doubt and despair …

Which is everybody. Everybody! We’re weak! That’s why I loved the westerns when I was a kid. We were stronger. Shane is strong. Watching them compensated for my own feelings of weakness. Of course, it depends on what you describe as real strength and character. You can hit someone and they stay hit … for a while. [Laughs] But that kind of strength is deceptive and not real.

We see that brutality often in your films. Does working through depravity and darkness help you find a path to decency?

Yes. The negative aspects of being human very often involve brutality and violence and the capability of violence. And you have to understand it. Or at least be ready to understand it. That’s all kinds. And I don’t mean, “Let’s be outré and say ‘The Age of Innocence’ is violent.” But a Jesuit in Rome the other day said it was a terribly violent film. You turn a card over and it’s all these different signs and signals of this tribe, which you’re ostracized from and it’s devastating.

Betrayal — another element found in so many of your movies. In the foreword to a recent edition of “Silence,” you said that in order for Christianity to live, it needs “not just the figure of Christ but the figure of Judas as well.” What do you mean by that?

Judas was God’s instrument for the sacrifice of Jesus. Did he want to betray Jesus? I don’t think so. That’s what we were trying to get across in “Last Temptation.” History labels him as the ultimate betrayer, but he was just doing the job that God had assigned him.

In “Silence,” the Judas figure, Kichijiro, keeps popping up — so often, in fact, his appearances become a form of comic relief.

Oh, absolutely! “It’s him again!” The thing about Kichijiro is that he ends up being the teacher. He’s the vehicle for compassion, helping Rodrigues understand weakness.

Also: Kichijiro does say, “It’s so unfair. If I had been born a few years before, there would have been no persecution. I could have been a good Christian.” As if he’s not a good Christian because he’s afraid. Or because he gives up all the time. It fascinates me. He comes back and begs for forgiveness and says, “I promise to be stronger next time.” And he does mean it, but he can’t do it. I think that’s all of us. That’s humanity.

Why do you think you’re so drawn to betrayal and traitors?

I think it goes back to the asthma I had as a kid. I was very much kept at home. Movie theater, church, go home. My parents had moved to Sunnyside, Queens, in ’42, but my father had a fight with the landlord and we were thrown out and sent back to where my father was born, which was 241 Elizabeth Street, my grandparents’ apartment. It was a pretty bad place, the Bowery, in the old days when the Bowery was the end of life.

And one of the predominant themes of living there was betrayal. And often the betrayal was deadly — deadly or ostracized in humiliation. Maybe it was that asthmatic or maybe it was just me, but I became ultra-sensitive. I sensed danger around all the time. I wouldn’t say I was fearful. I was just realistic. [Laughs] There were constant stories about people who informed. And many would wind up dead — or missing. So I grew up with that until I was 18, and then I moved to America, which for me was NYU. But I’ve never stopped being fascinated with stories of betrayal.

You were handed a copy of “Silence” right after “Last Temptation” premiered. Have your religious beliefs changed in the decades it took to make the movie?

The religious quest that brought me to “Last Temptation” took me to a certain point. “Silence” demanded more — an understanding of true faith. I know that sounds pretentious. But that’s what it is. Sorry. That’s who I am.

I am a product of the mid-20th century New York Catholic Church. A priest at St. Patrick’s Old Cathedral, Father Francis Principe, was my greatest mentor.”

— Martin Scorsese

For better or worse, I am a product of the mid-20th century New York Catholic Church. A priest at St. Patrick’s Old Cathedral, Father Francis Principe, was my greatest mentor. He was there from when I was 11 until I was 17. He was a real guide, a street priest. He taught us, “You don’t have to get married at 21 like your parents or grandparents. Find your calling. Find your own way.” An extraordinary man who possessed such love.

I wanted to join in his footsteps, but I could not. I didn’t have the real vocation. I looked at Father Principe and saw an absence of ego. I couldn’t understand how he let go his pride in order to serve. In a way, “Silence” is an attempt to work through that question almost 60 years later. Because that’s the very thing Rodrigues is struggling with as well.

He’s also struggling with the idea that God won’t listen to him. Or wondering if God is even there.

You remember in “Raging Bull,” Jake LaMotta sitting in front of that mirror at the very end, years later, and he accepts himself? That’s the beginning of God listening to him. But he’s got to forgive himself first. And a lot of people can’t do that. I struggle with that. We all do.

Constantly through “Silence” you hear the phrase, “I will not abandon you.” “I will not abandon you, Father.” But what if no one’s listening?

Ultimately, God tells Rodrigues, “I suffered beside you. I was never silent.”

Yet you still suffer. You don’t become St. Teresa of Avila. You don’t become a mystic Sufi. That takes so much work. I admire them. They can transcend themselves and go into another realm. That’s one of the reasons I did the George Harrison film [“Living in the Material World”]. I don’t know if he got it. But he was looking to transcend this world.

You premiered “Silence” at the Vatican and Pope Francis told you he hoped the movie “bears much fruit.” That’s quite a different response than “Last Temptation” received.

Somebody in Rome just asked, “What do you think is the difference?” “Well, this one they’ll see.” With “Last Temptation,” it never had a chance.

Are you interested in how evangelical Christians will respond to the new movie?

I’m curious. But I no longer feel like I have to convince anyone of anything.

And with “Last Temptation” you did?

Yes. Because I was being accused. And the movie may have been irreverent. It may have been what some people call blasphemy. Again, when you talk about it, it feels like a defense. And I don’t want to do that.

But understanding the human nature of Jesus … he has to be fully divine and fully human. And the teaching at Catholic schools emphasized the divine to the point where, if Jesus showed up in your classroom, you’d expect him to glow in the dark. So I wanted to get into that duality. But it was seen as a provocation. But the provocation was to think.

What does Christianity mean to you now, after making “Silence”?

It means a minute-by-minute, hour-by-hour relationship with Christ that’s been given to you. And that’s not easy. This is purely a layman talking. I’m not a theologian. I can’t argue the Trinity. But that relationship with Christ, that’s not something to take for granted.

And then you try to live your life as reasonably and considerately as possible. And maybe more. Then you have to go further. That’s what Christianity means to me. You have to give an example of who you are and how you behave and how you treat people. And maybe someone will look and say, “I want to be like him.”

See the most-read stories this hour »

Twitter: @glennwhipp

ALSO:

Colin Farrell likes his storytelling on the provocative side, as with ‘The Lobster’

Through ‘Hacksaw’ and ‘Silence,’ Andrew Garfield searches: ‘I want to know how to live’

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.