The key to adapting Phillip Roth’s ‘American Pastoral’? Focusing on the father-daughter story

More than a dozen years ago, when producers first approached me to adapt Philip Roth’s Pulitzer Prize-winning “American Pastoral” for the screen, I was sure I must be the wrong writer. After all, I had read it when it first came out, at a time when I was already a professional screenwriter — and yet it hadn’t occurred to me while reading it that this powerful but terribly complex novel could be a movie.

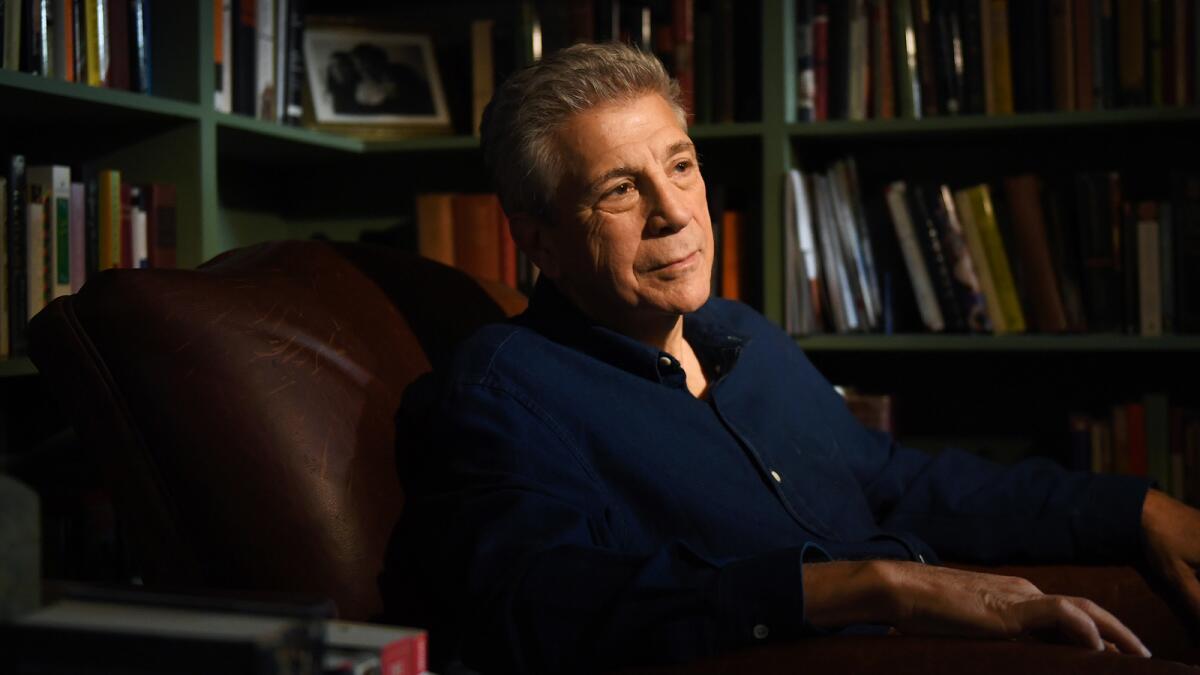

It was true that, back before I fell in with bad company and moved to Los Angeles to write for “Hill Street Blues,” I’d been a book reviewer for the New York Times and taught literature at Columbia, where I’d hold forth on how Roth was the best American novelist going — but that only made the task more daunting: How was I to capture his masterpiece in 120 pages? Script pages at that, cluttered, littered, with camera angles, fiercely abbreviated scenes, and CUT TO’s?

Above all, if the shape of the movie hadn’t leaped out at me when I read the novel in the first place, how could it be that I was its natural-born adapter?

The fact is, movies never do leap out of books. And being asked where to find the movie inside this one led me to ask what is always the right question for the adapter: What is there in a novel’s pages that makes for its greatest impact — emotional impact, that is, because what really keeps an audience where you want them (mesmerized, in a dark theater, held fast by what’s on the screen) is the claim the movie makes on their feelings.

Jennifer Connelly, Dakota Fanning and Ewan McGregor star in “American Pastoral.”

In the case of “American Pastoral,” that was one question I could answer. To begin with, the novel is sprawling, reaching out widely and brilliantly in many directions — from the decline of industrial America, the struggle of first-generation immigrant Jews to assimilate, and nostalgia for a patriotic childhood on the home front during World War II, to the violent, confounding ’60s and ’70s, with race riots in Newark, N.J., (my hometown, as it happened), the protests over the Vietnam War, and even Watergate. And yet lying behind and beneath this diversity and tumult, I saw, pulling the reader through by the heartstrings, is the loving but troubled relationship between Seymour “Swede” Levov and his daughter Merry — with wife and mother Dawn jammed awkwardly and tragically into their crossfire.

I realized at once that I had to center the movie on this nuclear family (thermonuclear is more like it, especially as it’s acted by Ewan McGregor, Dakota Fanning and Jennifer Connelly), with its universal father-daughter theme, going back to Lear and Cordelia and beyond, and transcending the novel’s wondrous specificity of time and place.

This decision on where to place the movie’s emphasis would, I knew, come at a cost: I’d be leaving out things I loved in the book. But nothing that did not stoke the engine of this emotional through-line could make it onto the page and therefore onto the screen. It was my good fortune that my centering of the father-daughter theme was supported by its producers at Lakeshore, Tom Rosenberg and Gary Lucchesi, and then by its director and lead actor, Ewan McGregor — all of them, like myself, fathers of daughters.

In making the film, we saw to it that much of the book’s rich historical background would come along with the movie’s telling, but if and only if it was crucial to the Swede’s heroic effort to recover and redeem his lost daughter. Whatever wasn’t would have to end up, not even on the cutting room floor, but on the floor around my corner table at the Casa Del Mar in Santa Monica (Yep, I’m one of those weirdly constituted writers who work in public places) where I’d spend mornings for the next decade or so writing the script’s next 30 versions — not a made-up number. The movie in which it resulted is one of which I am unimaginably proud, if only as the conveyor of Philip Roth’s profound, enduring vision of our nation and its troubled soul.

See the most read stories this hour »

ALSO

Ewan McGregor directs and stars in a timely adaptation of Philip Roth’s ‘American Pastoral’

Timely hot-button issues in film will always strike an awards chord

As he makes his directorial debut, Ewan McGregor reflects on the superstar path not taken

More to Read

From the Oscars to the Emmys.

Get the Envelope newsletter for exclusive awards season coverage, behind-the-scenes stories from the Envelope podcast and columnist Glenn Whipp’s must-read analysis.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.