An ‘Annie’ for grown-ups on Broadway

Anyone who’s seen “Annie” — and that has to be about half the nation’s population by now — knows exactly how the musical will start: half a dozen orphanage cots arrayed across the stage, each occupied by a singing waif.

But when the lights come up on the show’s new Broadway revival at the Palace Theatre, all of the young orphans are crammed into a single bed, looking more like Dickensian tenement dwellers than happy-go-lucky strays.

Although it’s an admittedly minor shift from the usual “Annie” opening, that hardscrabble staging underscores how director James Lapine and his cast and creative team have tried to dig the musical out from the high-gloss varnish that has been applied in thicker and thicker coats since the show premiered on Broadway 35 years ago.

Annie (played by 11-year-old Los Angeles actress Lilla Crawford) has ditched her cartoonish red wig. Orphanage mistress Miss Hannigan (“Promises, Promises” alumna Katie Finneran) comes across as more of a Eugene O’Neill washout than an outrageous lush. And although Oliver Warbucks (Australian classical music soloist Anthony Warlow) still sports a shiny bald head, he doesn’t milk the part for easy, slapstick laughs. Even the show’s stray canine, Sandy, is played by a rescue dog who was discovered just hours from being euthanized.

The musical about hard times, in other words, is essentially about hard times.

“I wanted to do a big show, but I didn’t want to do ‘Sugar Babies,’” Lapine said of that lighter-than-air burlesque review. “And when I read ‘Annie,’ it was talking to me about a lot of things I’d been thinking about, the times we are living in. I thought it was oddly topical. It’s kind of amazing to me that we are going to be opening around the election.”

Yet anyone worried about taking their young children to “Annie,” opening Thursday, shouldn’t fear a singing-and-dancing sisters grim.

Even with the show’s Depression-era setting — the story unfolds in 1933 New York — coupled with Lapine’s grittier direction, “Annie” is an upbeat story about a youngster overcoming adversity. The musical’s rags-to-riches heroine still teaches Franklin D. Roosevelt and her future adoptive father that no matter how grim things might look, the sun will, in fact, come out tomorrow.

Thomas Meehan, who wrote “Annie’s” book (the music and lyrics respectively are by Charles Strouse and Martin Charnin), said he always intended the musical to be for grown-ups. “It’s not a very well-known fact, but when we wrote ‘Annie,’ we did not write it for children,” Meehan said.

He said he was inspired to write the show following the 1974 resignation of President Richard Nixon. “It was our liberal Democratic protest against Nixon — to try to go back to a time when we had a more benevolent president,” Meehan said. “In 1977, people recognized what we were doing.”

The original Broadway production, starring Andrea McArdle as Annie, ran for 2,377 performances over nearly five years. It won seven Tony Awards, including best musical, and spawned countless national and international tours, school productions and a largely unsuccessful Broadway revival in 1997.

Meehan said the first entreaties from producers about another revival coincided with the election of Barack Obama in 2008. “They thought it had a new relevancy and would strike a chord,” Meehan said, particularly because of the financial crisis.

Not long after Meehan was contacted by potential producers, Lapine started looking for a new project. In early 2010, Lapine had conceived and directed the “Sondheim on Sondheim” revue on Broadway, where he previously had staged “The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee,” “Into the Woods,” “Passion” and “Sunday in the Park With George.”

The theater veteran somehow had never seen “Annie,” adapted from the Harold Gray comic strip “Little Orphan Annie.” “I just didn’t really know it,” Lapine said. “So when I read it, I was really impressed by it.”

The show’s musical vocabulary, while seemingly straightforward, is relatively ambitious and the book deceptively well plotted. In addition to having an array of indelible songs — chiefly “It’s the Hard-Knock Life,” “Tomorrow,” “Easy Street,” “Maybe” and “You’re Never Fully Dressed Without a Smile” — the musical opens itself to plentiful interpretations.

Lapine immediately decided that Miss Hannigan, who was played by Dorothy Loudon in the original 1977 Broadway production, Carol Burnett in the 1982 movie, Nell Carter in the 1997 revival and Kathy Bates in a 1999 TV movie, should be depicted by someone younger who would perform less broadly, leaning toward naturalism and away from caricature.

“I just thought it was more interesting with a younger, sexier person,” Lapine said. That way, the director said, when you see her running the orphanage “you can see that her youth is being stolen from her.”

So he met with Finneran, who recently had won the featured musical actress Tony for “Promises, Promises.” At her audition, the 41-year-old actress was eight months pregnant but nevertheless wore stiletto heels. Her Miss Hannigan wasn’t going to be dowdy.

“I think she had very limited options, and she doesn’t belong there,” Finneran said of what she imagined was Miss Hannigan’s back story. “And she always has one foot out the door — she sees an opportunity to escape with every man who walks by.”

The actress worked closely with costume designer Susan Hilferty and makeup head Ashley Ryan to ensure that the character didn’t look too good — her clothes are more than a little frayed, and the roots of her hair show it’s been a long time since she could afford a proper dye job.

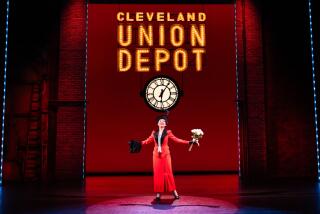

The show’s production design, by David Korins, evokes distinct references. The musical’s homeless encampment is based on photographs of actual Hooverville shantytowns; changing backdrops in Warbucks’ mansion partially call to mind turning pages from a book-length collection of “Orphan Annie” comics.

“I wanted there to be reality,” Lapine said. “I didn’t want it to be a cartoonish Depression.”

His most critical choice was in casting Crawford as Annie. Chosen from more than 5,000 kids who were considered and 150 who auditioned, Crawford has a great singing voice and some Broadway experience — she was in the cast of “Billy Elliot”— but what really sold Lapine was her soul.

“She’s not a show kid — she lives the part,” Lapine said. “A lot of kids bring nothing of themselves to it. She’s complicated.”

The young actress understands that she isn’t supposed to play Annie as “too peppy. She’s not exactly mean, but she’s tough.”

The Broadway revival is but one of several “Annie” resurrections in the works. Rapper Jay-Z and Will Smith are producing a planned Sony movie that might star Smith’s daughter, Willow, and Rabbit Hole Comics (run by Tribune Media Services, an affiliate of the owner of the Los Angeles Times) this month is introducing a new action-oriented “Annie” ebook series from artist Ted Slampyak and comic historian Jay Maeder.

Meehan and Lapine said the renewed interest isn’t entirely coincidental.

Warbucks certainly represented the top 1% some 80 years ago, and the gulf between the haves and have-nots has only grown more dramatic in the intervening decades.

“It’s right there — right in front of you,” Meehan said.

Added Lapine: “Especially in New York, the disparity between the rich and the poor is astonishing.”

Even though the show’s producers are working to bring lower-income kids to the show, it still takes quite a few pretty pennies to see “Annie” — a single premium orchestra seat costs $238, with other orchestra seats running more than $175. “I know, I know,” said the actress Finneran. “It’s a very isolated community that gets to see shows.”

Lapine hopes those prosperous enough to come to the musical walk out of the Palace considering more than the sets, costumes and acting. Although he doesn’t intend “Annie” to be agitprop, he expects that his staging might open some eyes to some of the misfortune around them.

“I don’t think that’s impossible. You hope that any work of art can have an impact,” Lapine said. “But you don’t want to hit the audience over the head with it. You want it to be subliminal in that way, so that maybe they are thinking about it when they leave.”

MORE:

CRITIC’S PICKS: Fall Arts Preview

TIMELINE: John Cage’s Los Angeles

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.