Critic’s Notebook: After five years of Gustavo Dudamel, what’s next?

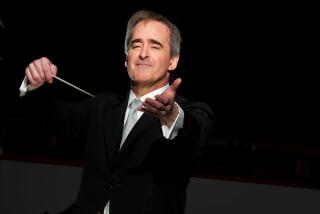

When a bushy-haired 28-year-old with a magnetic podium presence became music director of the Los Angeles Philharmonic five years ago, Gustavo Dudamel galvanized the classical music world and beyond.

------------

FOR THE RECORD:

Master Chorale: An article in the Oct. 26 Arts & Books section about conductor Gustavo Dudamel’s fifth anniversary leading the Los Angeles Philharmonic misspelled the name of the Los Angeles Master Chorale as Choral. —

------------

At the Venezuelan conductor’s insistence, the gates of the Hollywood Bowl were thrown open to the community, with free tickets for all. After a proud-papa warm-up with youngsters in Youth Orchestra Los Angeles — a group inspired and founded by Dudamel — he led the L.A. Phil, Master Choral and stellar vocal soloists in an exuberant performance of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony.

The Dude, as he was affectionately called, spread the joy of Beethoven’s famous “Ode to Joy” as easily as if it were jam on bread. The mood in the Cahuenga Pass resembled that of a victory rally. The concert was front-page news.

Not only was Dudamel, in the words of his L.A. Phil predecessor, Esa-Pekka Salonen, “a conducting animal” but he was also being hailed as a savior, a symbol for musical and social betterment.

Yet for all its genuine excitement, that Beethoven Ninth performance wasn’t a great one. The symphony sometimes lurched from one exhilarating moment to the next. The sense of occasion is what mattered, as did this Dude’s seemingly unlimited potential.

So where do things stand now with Dudamel, five years on and midway through his 10-year contract with the L.A Phil?

There had been reasonable skepticism from the outset, not the least from Dudamel himself. He had his mission. Insisting that music was a human right, he said he wanted to bring it into the lives of as many, young and old, privileged and otherwise, as he could. But he loathed the savior nonsense.

There was also a not unreasonable backlash. Dudamel seemed simply too good to be true, especially to dubious East Coast critics. The enormity of his talent and musical technique was not in question; orchestral musicians were among those who showed him the highest regard.

But flashy dudes don’t necessarily age well. Clearly, he could inspire, but could he lead? Saviors tend to stop growing once they begin preaching. What was Dudamel’s capacity for growth?

There is no musical calculus to assess this kind of moving target. He can change from season to season, from month to month even. But Dudamel has shown an exceptional deepening as a conductor, and the biggest change has occurred since the beginning of the year.

He was, for instance, back at the Bowl conducting Beethoven last summer, this time the Fifth Symphony. What he brought to it was less immediacy than urgency. Forget the boyishly spreading joy like jam for all to enjoy. Forget the Dude. Forget the savior. Here, Dudamel was conducting as a seeker. Through telling details and stirring psychological narrative, he strove to reveal Beethoven’s deep motivations for conjuring triumph from torment. This performance offered, at the very least, the intimation of greatness.

And so did Dudamel’s account of another Fifth — Mahler’s — that opened his sixth season at Walt Disney Concert Hall. The symphony makes the same journey as Beethoven’s, from angst to euphoria, but on a considerably larger scale and through a far more angst-ridden path. In what may well have been his most penetrating performance with the L.A. Phil, Dudamel was able to go beyond vividly bringing out the individual character of phrases, long his métier in Mahler, and deal with the symphony’s profound, unanswerable questions.

You need only to compare this Fifth with a new recording Dudamel made of Mahler’s Seventh with his other orchestra, the Simón Bolívar Symphony of Venezuela, early in 2012. He had just finished an unprecedented feat of conducting cycles of Mahler’s nine epic symphonies in L.A. and Caracas over a month, dividing the scores between the L.A. Phil and Bolívars.

His captivating live performance of the composer’s most problematic symphony, known as “Song of the Night,” taped in Caracas, is suffused with the Seventh’s emotional extremes. But compared with Dudamel’s meaningful and considered recent Fifth, this is still Mahler raw and immoderate.

To some extent, the factors that have compelled Dudamel’s rapid development must be guessed at, but three stand out. First and probably foremost has been his residency in L.A., where he has been given permission to take chances and learn from his mistakes.

In its 17 years under Salonen, the L.A. Phil had become the most venturesome major orchestra in the land. It had the invaluable added attraction of Disney Hall. Salonen made this a fabulously flexible ensemble, with an unusual appetite for new music and startling new challenges.

Dudamel jumped in like a conducting kid in a philharmonic candy shop. He wanted to do everything, be it standard symphonic repertory or all kinds of new music, from avant garde to pop.

For his first week of concerts at Disney as music director, in fall 2009, he led two major world premieres — John Adams’ “City Noir” and Unsuk Chin’s “Su,” a concerto for Chinese mouth organ (the sheng) and orchestra. Both have gone on to be widely performed, and both have been newly recorded by other conductors and orchestras.

Dudamel has made opening each season with a new commission a tradition. By now his commitment to new music is such that the L.A. Phil far out-numbers any other nonspecialist ensemble in its commitment to living composers.

L.A. has also been a place where Dudamel can experiment in other ways. Under Salonen, the orchestra had become a pioneer in mounting festivals and inventively staging opera, and Dudamel has upped the ante with increasingly ambitious projects of his own. His pet festival has been the ongoing music from the Americas and Americans. He has staged Mozart’s three Da Ponte operas in Disney Hall and premiered Adams’ most recent opera, “The Gospel According to the Other Mary,” yet another L.A. Phil commission.

Playing in and conducting orchestras in Venezuela’s El Sistema from childhood, Dudamel arrived in L.A. well prepared. In 2007, two years before taking over in L.A., he began a five-year stint as principal conductor of the Gothenburg Symphony in Sweden. This was mainly to get the hang of leading a professional orchestra as well as learn new repertory out of the limelight.

Even so, Dudamel’s early performances in L.A. could exhibit a surprisingly seat-of-his-pants interpretive character. He typically arrived at first rehearsals having memorized even the biggest and most complex scores, which he obsessively went over and over in his mind as a form of mental gymnastics. But many times when conducting a piece for the first or first few times, he might try something different at each performance. Often what hadn’t worked on Thursday night did on Sunday afternoon.

The capacity to take chances and learn from mistakes is a necessity for genius. Dudamel is a big risk taker and a fast learner.

Venezuela, on the other hand, has nurtured Dudamel’s maturity in a very different way. As his international fame grew, Dudamel increasingly became the international symbol for El Sistema and a beloved superstar at home, mobbed by screaming teenage girls and drafted by the Venezuelan government (which underwrites El Sistema’s $100 million-plus yearly budget) for official national celebrations and functions.

But with Dudamel’s country in turmoil, Venezuelan politics have made life difficult for him. He is faulted for anything he does or says or doesn’t do or say, either by those who support and depend upon the socialist government of Nicholás Maduro or those who blame the president for the country’s economic chaos and human rights abuses.

Dudamel has not disassociated himself from the government, but he has spoken out for nonviolence and freedom of speech and assembly. His position has been to put his faith in El Sistema, which consists of young musicians growing up together and playing music together, whatever their political or social differences.

Emotions, however, run high, and Dudamel has lost friends and made enemies. The new gravity and urgency in his Beethoven and Mahler cannot be unrelated to his new appreciation of a less-than-rosy world.

Finally, there has been Dudamel’s rapid acquisition of European sophistication. Although he has become the most sought after of conductors, he limits his guest appearances to a handful of top or favored orchestras overseas, with most of his attention going to the Vienna Philharmonic and the Berlin Philharmonic. He is rumored to be a candidate for Berlin when Simon Rattle steps down in 2018. Vienna does not have a music director, but Dudamel just finished a monthlong residency with the orchestra, touring in Europe and Asia.

At a concert I heard him conduct in Vienna last month, he found the Vienna Philharmonic’s creamy essence, as though he were an inventive sonic chef bringing out natural ingredients of the Viennese sound in ways no one else has thought to do. The oft-haughty players looked as though they had just discovered rapture.

It would, of course, be foolhardy to predict the next five years for Dudamel. Losing his boyishness, to say nothing of his dude-ishness, has not meant losing his charm. He is young and energetic, and he will probably be tempted by crazy challenges and take big chances. We all now have our favorite pieces we’d like him to champion. I would propose he look at Henry Cowell’s neglected ur-Californian symphonies. But Dudamel already has remarkably wide repertory antennae, and it is he who will likely surprise us.

Dudamel may not be a savoir, but he has become a leader and appears more driven than ever to make a difference.

Twitter: @markswed

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.