Heavenly emissaries Royal Ballet of Cambodia descend on Long Beach

Twenty-four years ago, the Classical Dance Company of Cambodia astounded audiences at the Los Angeles Festival with its ritual dances and stories of fantastical demons and mythical goddesses.

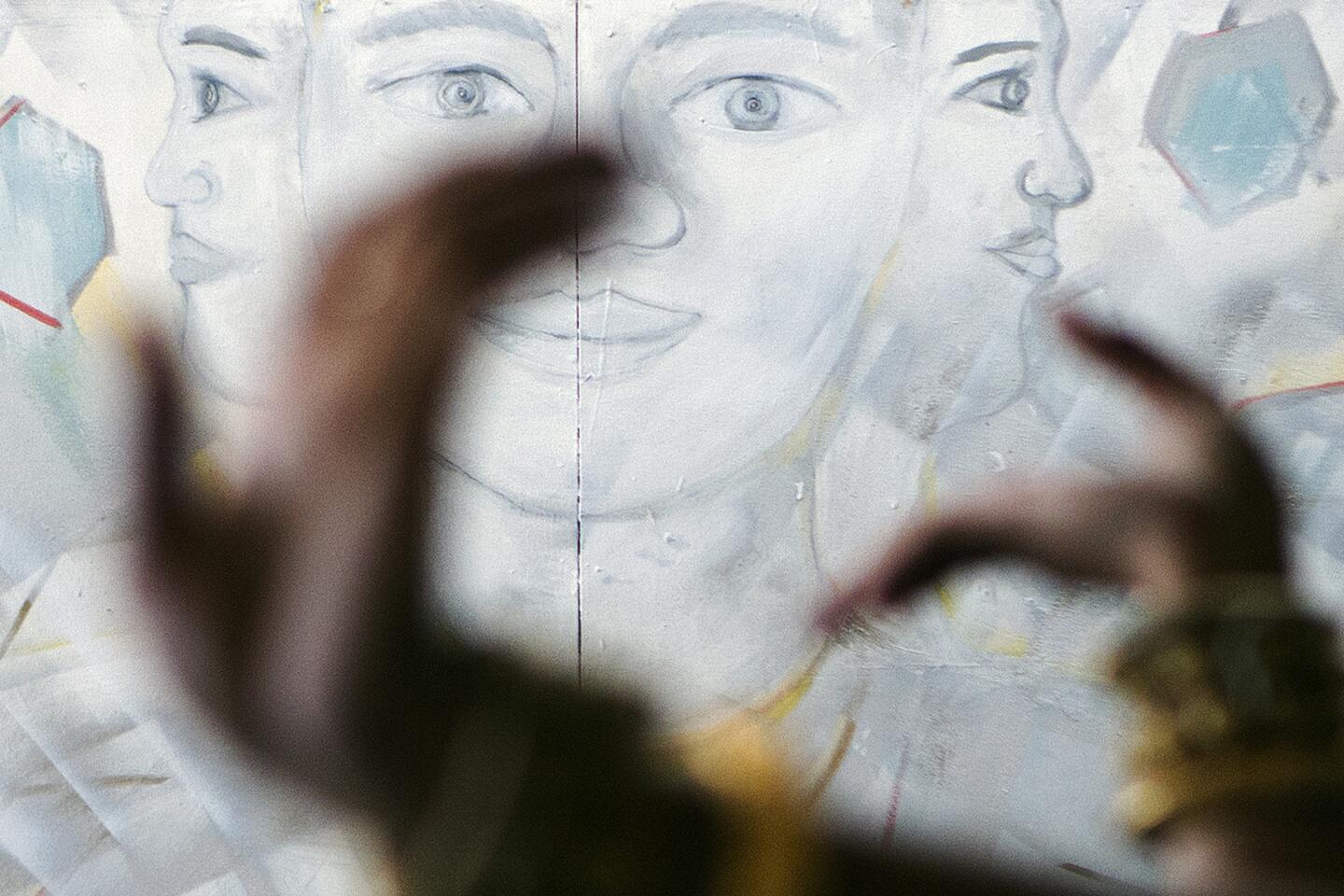

The female dancers appeared to float, thanks to their mastery of a grounded but flowing heel-to-toe gait. Their elbows, toes and fingers were curved backward in hyper-extended poses that defied nature and bone structure.

And the troupe’s back story was chilling: The classical Cambodian dance had been saved from near-oblivion during the Khmer Rouge regime of the late 1970s, when an estimated 90% of the country’s artists, including its dancers, were killed. But a determined effort to revive it led to its reemergence a mere 11 years later.

Now the country’s leading classical dance troupe, which is today called the Royal Ballet of Cambodia, returns with eight dancers and five musicians for a single performance Saturday in Long Beach.

Preservation of this 1,000-year-old art form is still the company’s primary purpose, but much has changed, says ballet master Proeung Chhieng, who helped spearhead the revival after the Vietnamese expelled the Khmer Rouge in 1979. He was artistic director of the group that performed at the Los Angeles Festival.

“Before, the dancers are temple dancers so they are like monks,” he said. “Now, we are human beings and are at peace. We obey the gods and perform … but they dance the role of the story, and they dance like European dancers.”

That is, the days when dancers lived in the royal palace, enjoying special privileges and performing only for the aristocracy, are long gone.

Hundreds of years ago, these women — men now have limited performing parts — were dedicated to the magnificent temples that are decorated with their images in bas relief. Their role was to be a bridge between heaven and Earth, sending prayers to the gods for rain and for good crop yields.

The classical dance once again enjoys an imperial association, as it is led by the daughter of King Norodom Sihanouk, Princess Buppha Devi, who was a star dancer in the 1960s. The current full troupe of about 40 dancers are not spiritual emissaries, however, but cultural ambassadors — and entertainers.

Cambodian dance, in general, is reaching new heights, said Prumsodun Ok, associate artistic director of Khmer Arts — a school and company with bases in Long Beach and Takhmao, Cambodia; it is led by Sophiline Cheam Shapiro, who performed at the 1990 Los Angeles Festival.

“At the Royal Ballet, it’s a really interesting dynamic because for so long they were kind of the voice of preservation. Even today, there’s a recognition that tradition is something that’s always moving,” Ok said.

For viewers making their first foray to Cambodian classical dance, it can be a mesmerizing but also disorienting experience because the style is so different from Western dance technique. In many instances, poses have specific meanings; hand gestures can symbolize flowers or leaves. Ok pointed out that it’s not necessary to understand the significance of each gesture but more important to appreciate the dancers’ performance quality.

“When you’re looking at the dance, remember it’s based on an aesthetic of curves,” he said. “That aesthetic is important. Because our ancestors were animists. Animism is the belief that trees, the water, the natural world all have spirits. The serpent was a very important symbol; it conjured the image of flowing water, of rivers cutting through the Earth. So to invoke the serpent in your body is to invoke the life-giving waters.”

Principal dancer Chamrouentola Chap began training when she was 7. Her parents enrolled her in a special school that offered dance lessons every morning and general subjects the rest of the day. She was not so interested at first but soon became passionate about it. Following nine years of study, she is now a leading performer, a teacher at the Royal University of Fine Arts in Phnom Penh and a choreographer.

She said the hyper-extended positions the dancers achieve are accomplished through years of consistent applied pressure: “We bend those fingers, except the thumb, the four other fingers, we bend it every day, step by step.”

For all the work that has been done to ensure that the technique is being passed on, the dance’s long-term survival also depends on other incremental steps — in this case, whether there will be enough financing to keep it alive. Money is tight.

Said Chhieng, the master dancer: “We cannot perform often [within Cambodia]. We try to look for a sponsor or an NGO or a foundation abroad.”

In 2003, UNESCO designated the Royal Ballet an “Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity.” The hope is that the dance troupe that survived the Khmer Rouge will keep the country’s traditions alive for the next generation.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.