Review: What to see in L.A. galleries: Betye Saar, Tom Knechtel, Kay Sekimachi

Birdcages. Boxes. Shrines.

Eyes, keys, dice, cotton and clocks.

Washboards, chains, ships.

Betye Saar works with materials that have long metaphorical half-lives and with metaphors that she assigns striking material form. It's tempting to liken her to a chemist handling potentially toxic substances, but most of the found objects in her assemblages are familiar — and ordinarily benign. She releases their potency and reactivity through isolating and recombining them. She is more like a poet who takes everyday language, spikes it with terms obsolete and retrograde, and invests it with new resonance through the tools of disjunction, recontextualization, concentration and enjambment.

Saar, 90, is what the Japanese would term a living national Ttreasure. Any opportunity to see her work is a privilege, one that promises to wrench, incite and nourish. The work oscillates between toughness and beauty and typically fuses the two.

Roberts & Tilton's current show is divided into two parts that opened on staggered dates but now present as a single, selective survey. The 28 works span from 1964 to the present and include sculptures, installations, mixed-media paintings, drawings, collages and a single print. It's not the 80-work overview underway at the Prada Foundation in Milan, Italy, nor the 135-piece retrospective that traveled earlier this year from the Netherlands to Arizona. It doesn't pretend to capture the L.A. native's breadth, but it more than hints at her depth.

The show also demonstrates that Saar has not yet exhausted her vocabulary of forms and ideas. Several recent pieces have just as much emotional texture, vigor and relevance as those that established her reputation decades ago. "Serving Time" (2010) nimbly links today's incarceration epidemic among African American men to earlier patterns of segregation and oppression. Inside an old, standing birdcage festooned on the outside with padlocks and keyrings are three crudely caricatured black male figures, a clock and a crow figurine, Saar's ominous, oft-used reference to Jim Crow.

SIGN UP for the free Essential Arts & Culture newsletter »

In "The Destiny of Latitude & Longitude," also from 2010, a tall billowing dome of a cage encloses two miniature ships, another recurring motif for Saar, as is the notorious diagram of enslaved Africans packed in a ship's hold. One vessel here dangles beneath a wire moon, and the other sails on a sea of gray tresses. Three antique wire glove forms press imploringly against the cage's mesh walls. The feet of a little bird are bound by wire, a small globe rests in the mouth of a metal shoe, and a padlock fastens a long gray braid to the wall of the cage. By juxtaposing images that operate on such different scales, Saar invokes continuity between the intimate and the more broadly social: captive soul, captive body, captive culture.

Throughout, secondhand objects dense with their own histories suggest larger historical narratives, forces and fates. The destiny of these discards, it seems, was to serve as building blocks in a poetry of yearning, praise and lament.

Roberts & Tilton, 5801 Washington Blvd., Culver City. Through Dec. 17; closed Sundays and Mondays. (323) 549-0223, www.robertsandtilton.com

Provocatively installed just inside MIM's gallery door, Kenneth Morehouse's "Impressions of Stone" reads at once as a collection of photographs, a section of flooring, a riff on Carl Andre's metal plate grids and a reverberant poke at what constitutes truth in representation.

All of the 16 plexiglass tiles (each measuring 94 inches by 94 inches) are back-printed with a grid of photographs of paving stones and concrete incised to mimic them. The piece marries traditions rooted in the late '60s — minimalist sculpture and conceptual photography, especially the work of Kenneth Josephson — to land irreverently, unavoidably, at today's doorstep, setting the mind aflutter with its self-referentiality and layers of surrogacy.

Morehouse's work ushers us into the group show, "Number Six," whose participants all put photography to some sort of unconventional use emphasizing materiality. Despite some simplistic work, the show has plenty of piquant moments to compensate.

In her two "Memories" pieces, Shadi Yousefian gathers hundreds of tiny photo-portraits, slips each like a specimen into its own plastic or glassine bag and nails them to a wood panel in a tight grid. Intimacy meets detachment in this personal archive.

Sasan Abri's "Conjunctivitis" series of large inkjet prints invokes the condition's symptom of compromised sight. The pictures are blurred, their colors bleached. They intrigue in direct proportion to what they withhold.

Zachary Roach prints photographs on 26-inch-diameter relic-like concrete in "Tablets"; two lean against the wall, and one lies cracked apart on the floor. The images are distorted, incomplete portraits, yellowed as if from the distant past, and that elusiveness clashes marvelously with the palpable physicality and daunting weight of their support.

MIM, 2636 S. La Cienega Blvd., Los Angeles. Through Oct. 29; closed Sundays and Mondays. (424) 299-8223, www.mim.gallery

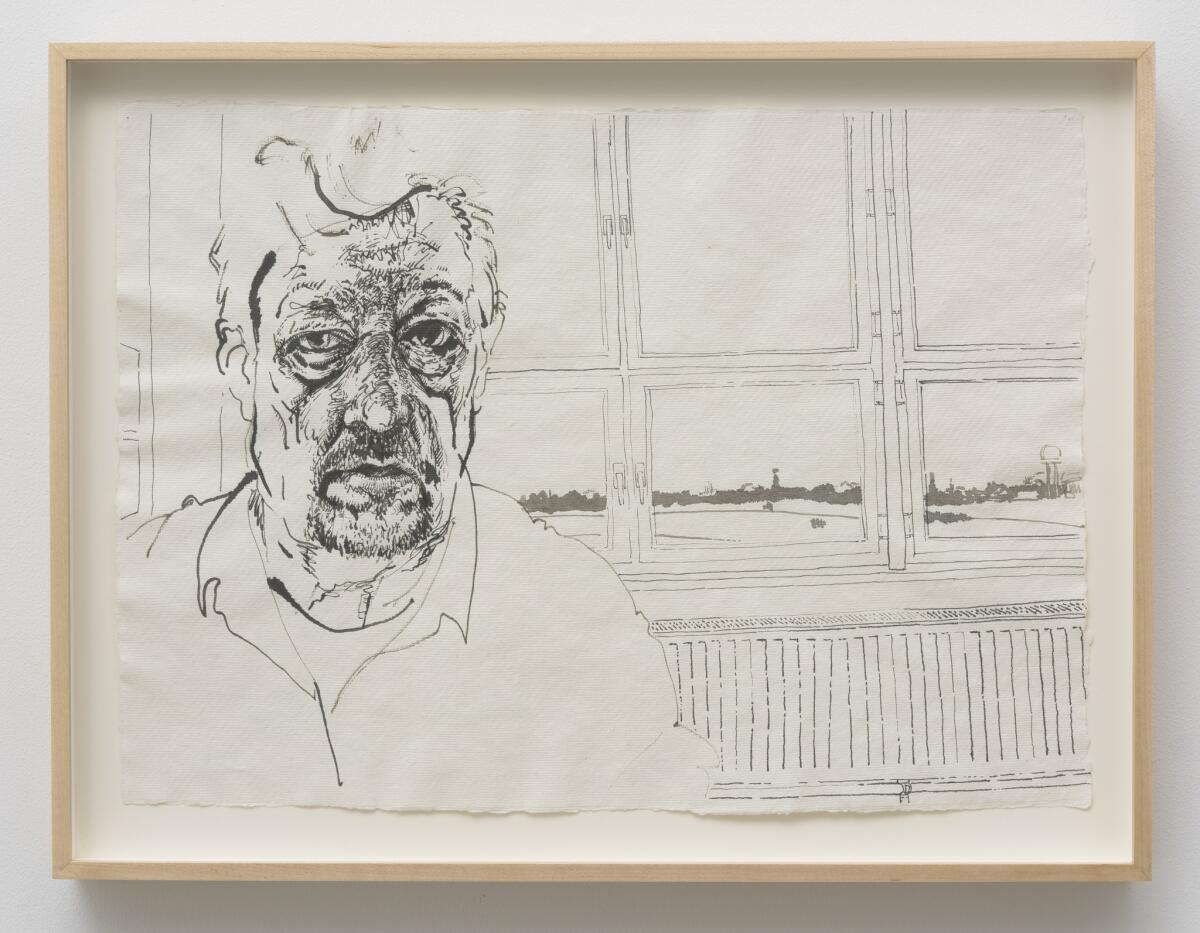

"I Stand in the Mess of Myself," the working title for Tom Knechtel's deeply stirring show at Marc Selwyn Fine Art, was borrowed from one of its 30 ink drawings. What became the show's final title, "Astrolabe," is a reference to an antiquated navigational tool and a nod to his overall enterprise: seeking orientation in that curious mess of the self, that made-to-fail engine of multiplicity, simultaneity, wonder and contradiction.

Knechtel's work of more than three decades has largely seized upon the montage nature of experience, and two large paintings here evoke that temporal, sensory stew. The notebook-sized drawings deviate into the zone of singular focus — portraits and self-portraits, primarily — but often prove more complex.

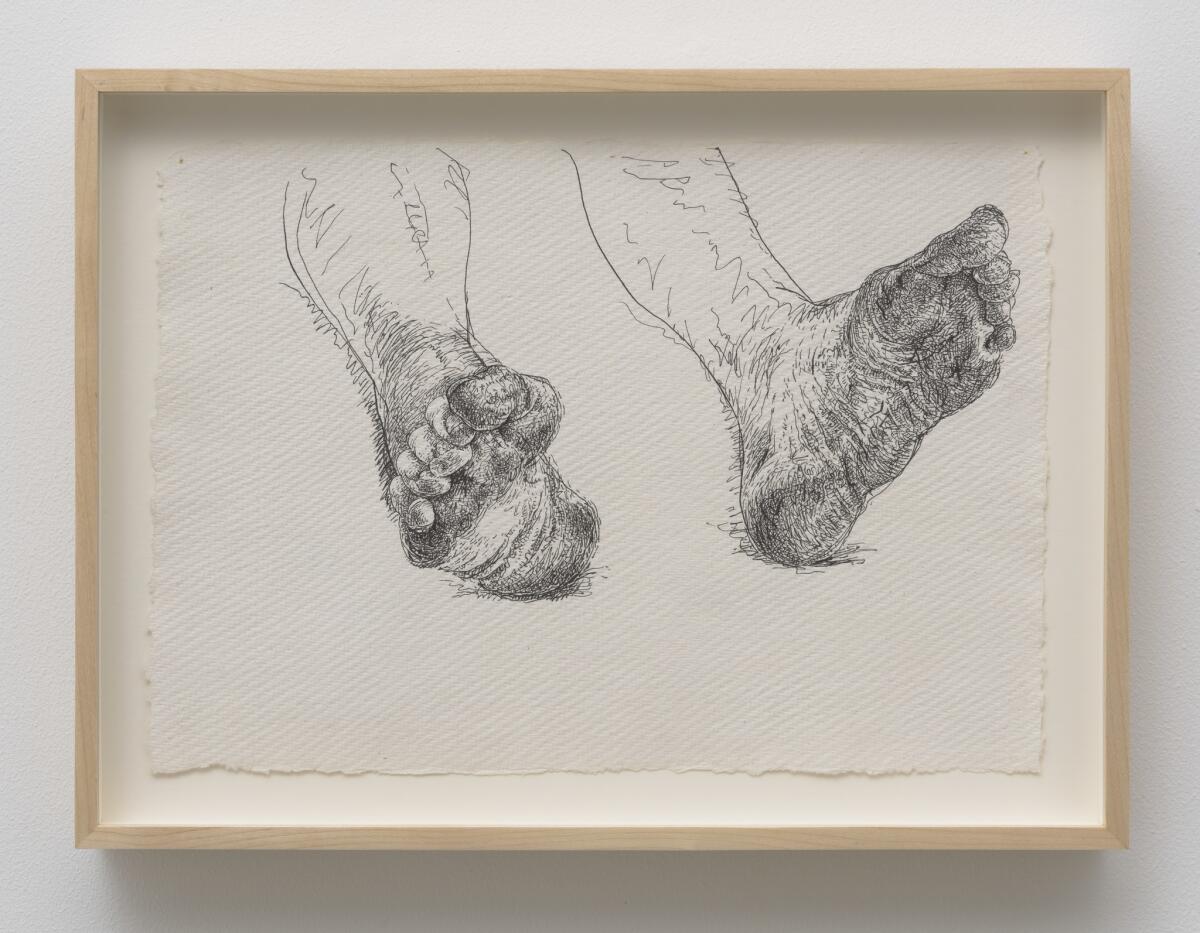

"Bob's Feet (4)" ripples outward from tender, direct observation to meditation on mortality, humility, reverence. Knechtel draws the feet of his reclining husband from below, looking from the soles upward, a perspective that speaks at once of the intimacy of the bed and the chill of the morgue, reverberating all the while with the echo of Andrea Mantegna's famously foreshortened "Lamentation Over the Dead Christ" (circa 1490).

A companion show of the artist's prints and drawings at CB1 Gallery makes this a season to feast on Knechtel, and what exquisite nourishment he offers. From the ink-pooled circles under his eyes in a piercing "Tempelhof" self-portrait to the alien creature he finds between his legs in the jarring, luminous little painting "Salamander," Knechtel is ever rendering nakedness itself, and not just as a matter of bared skin.

Marc Selwyn Fine Art, 9953 S. Santa Monica Blvd., Beverly Hills. Through Oct. 29; closed Sundays and Mondays. (310) 277-9953, www.marcselwynfineart.com

Kay Sekimachi works in an astonishing range of materials: paper, wood, paint, ink, dye, shells, leaves, hornet nests. But she is primarily known as a fiber artist, relegated to that condescending sub-category reserved for those who use tangible lines, as opposed to those (just plain artists) who draw and paint them.

Raising again and again such hierarchical assignations can, admittedly, get tiresome, but sometimes the discussion spits out new, irrepressible questions.

"Simple Complexity," a handsome and at times breathtaking show at the Craft & Folk Art Museum, touches down lightly across the range of Sekimachi's nearly 60-year output. A 1960 woven room divider introduces the Bay Area artist's inventive lyricism within conventional, functional formats. Flax fiber bowls from 2008 are pure suspended fluidity, the plant's hairs alone defining the vessel form's swirling momentum.

Two hanging monofilament sculptures are marvels of technical ingenuity, the multiple woven planes flowing together and apart as permeable membranes, akin to the undulating, bulbous, crocheted metal forms of Ruth Asawa. Sekimachi's work talks richly with the work of others, and not just fiber artists, another reason to dissolve those hierarchical barriers and embrace instead a more democratically diverse art history.

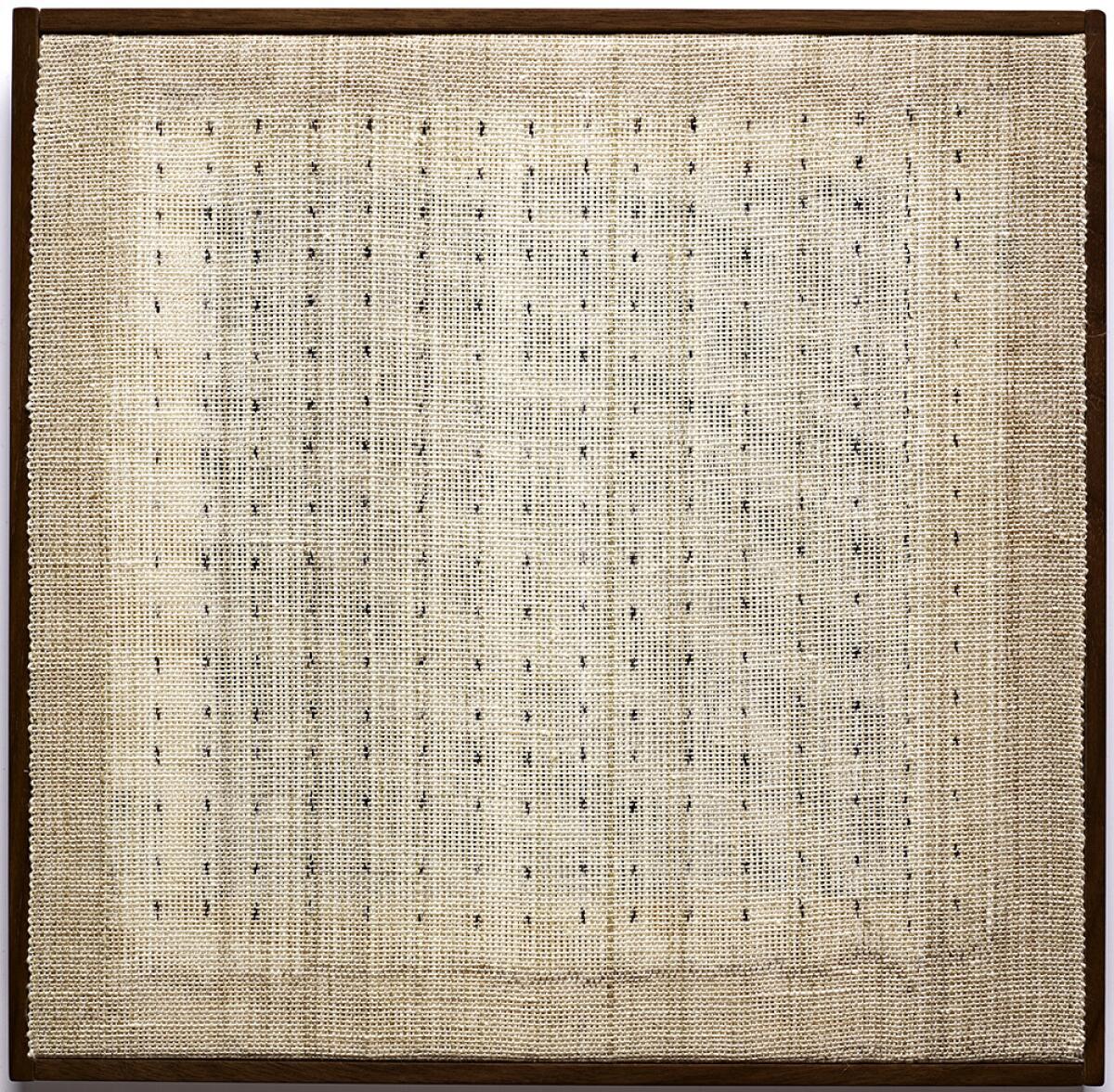

"100 Views of Fuji" (1981) is a small, double-woven linen accordion book, transfer-printed with pale violet silhouettes of the sacred mountain. It pays elegant tribute to the woodblock printer Hokusai. Three small square wall pieces, woven linen fields with lines and dots accentuated in dye and marker (2011 and 2014), are direct homages to Agnes Martin, who was influenced by weaving. These beautifully reductive grids speak in a shared language, as if pages of their private correspondence.

Craft & Folk Art Museum, 5814 Wilshire Blvd., Los Angeles. Through Jan. 8; closed Mondays. (323) 937-4230, www.cafam.org

Follow The Times’ arts team @culturemonster.

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.