Critic’s Notebook: Elisabeth Moss, Carey Mulligan share a sensibility on separate stages

There’s a moment in the new Broadway revival of Wendy Wasserstein’s “The Heidi Chronicles” when Heidi, the art historian holding fast to her liberated ideals while wrestling with loneliness, takes a cheap shot at the latest young catch of her old flame, Scoop Rosenbaum, whom she ran into at a John Lennon memorial in Central Park.

“Yes. Fishnet Stockings has opinions,” Heidi tells her girlfriends at a baby shower where Lennon’s “Imagine” has been dolefully playing in the background.

As soon as Heidi — newly incarnated by Elisabeth Moss in Pam MacKinnon’s production at the Music Box — utters this remark, she waves her hand as if to erase her words. With this little gesture, Moss’ Heidi does more than indicate her regret — she acknowledges the gap between her political platforms and her emotions.

Just across the street on West 45th Street at the Golden Theatre, Carey Mulligan is also playing a woman trying to stay true to her principles regardless of the costs. As Kyra, the self-abnegating teacher of David Hare’s “Skylight” in Stephen Daldry’s sensationally acted production, Mulligan has a look that suggests her character has forsworn pleasure.

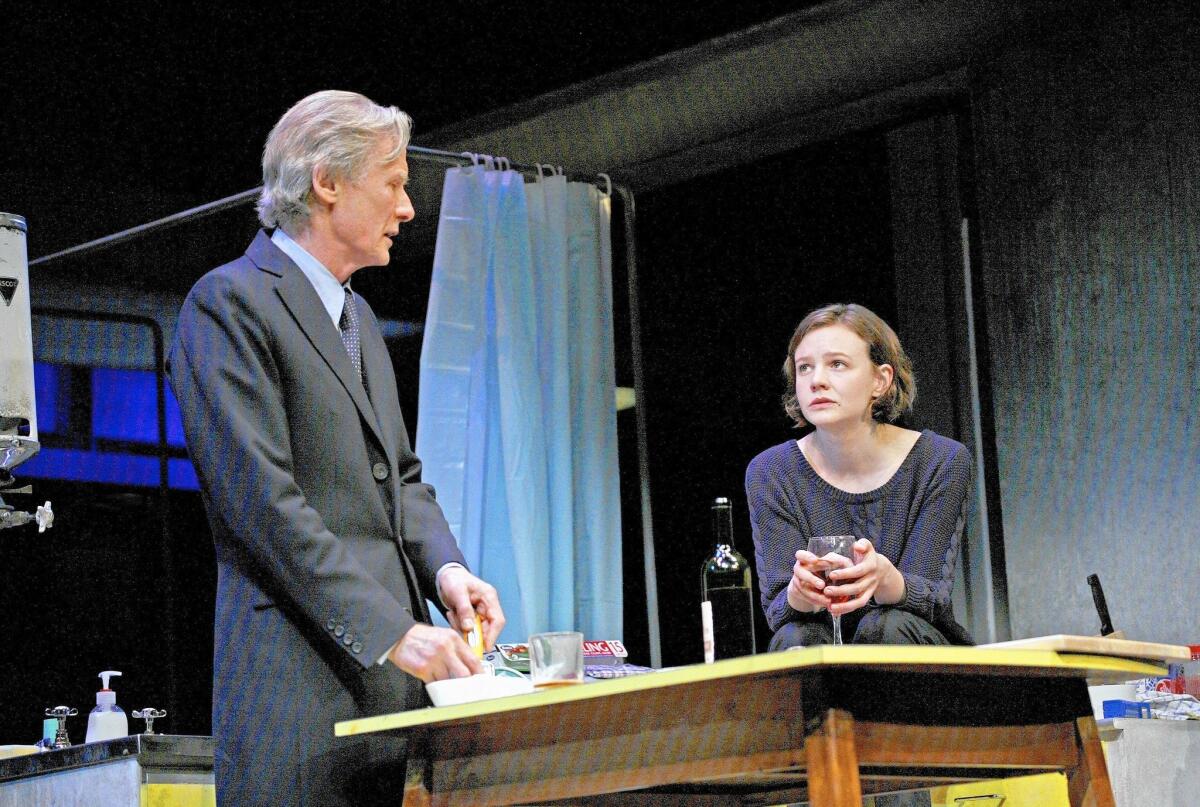

Pretty but conspicuously wan, she is like a modern day Simone Weil, existing entirely for the benefit of those less fortunate. Her inadequately heated apartment is in a rundown neighborhood requiring a ludicrously long commute to the equally dingy neighborhood where she teaches. When her older, wealthy and unabashedly conservative restaurateur ex-lover Tom (Bill Nighy) shows up at her door years later, Kyra will have to decide whether her worldview can again accommodate his diametrically opposed one.

The personal, as the old shibboleth goes, is political. A lesser-known corollary to this is that the more personal the politics, the more riveting the drama. On stage, placards and propaganda induce yawns. But a character grappling with choices of prodigious ethical or moral weight lures us in. Thus conscience does make protagonists of us all, as Hamlet would have said had he reached middle age.

Moss didn’t strike me as a natural for Wasserstein’s highly decorated drama (winner of the Tony and the Pulitzer), though her character on “Mad Men” has long been waging feminist battles. Joan Allen, who originated the role on Broadway in 1989, set the model for a Heidi who is mature, statuesque and impressive even when diffident.

Moss is a more discreet presence. Her keen intelligence is revealed in the bottomlessness of her stare. Like Robin, the detective in the hypnotic miniseries “Top of the Lake,” Moss’ characters see more than they let on. Moss was exceptionally good in her Broadway debut in the 2008 revival of David Mamet’s “Speed-the-Plow,” playing a secretary who outwits a couple of male Hollywood executives. But then she excels at drawing attention to the latent gifts in women who might otherwise pass unnoticed.

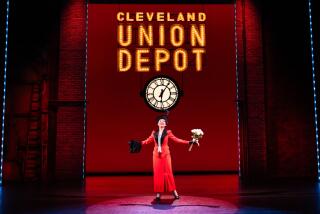

Her everywoman attributes — natural charm, emotional honesty, secret smarts — turn out to be just what’s needed to introduce a new generation of theatergoers to Heidi. The play, which goes from the start of the women’s movement in the 1960s to the aggressively self-seeking, capitalist late 1980s, is now more than 25 years old, making it nearly half a century removed from the revolutionary heyday of Second Wave Feminism.

The catch phrases and cultish markers of the movement no longer have the same cultural resonance. Moss, the bright spot in MacKinnon’s uneven revival, portrays Heidi not as an emblem of the shifting zeitgeist but as a very particular woman coming to the realization that “having it all” may not be possible for anyone, no matter how gifted and enlightened.

The problems with the production are legion. John Lee Beatty’s sterile scenic design creates a drab no-woman’s-land, and Jessica Pabst’s costumes turn the supporting actresses into time-capsule caricatures. The male performers are badly miscast — Jason Biggs’ Scoop hasn’t a drop of charisma, and Bryce Pinkham’s Peter, Heidi’s gay BFF and former quasi love interest, is a stage personality, rarely a person.

What is thoroughly enthralling, however, is the sight of Moss’ Heidi communing with her own misgivings. When “The Heidi Chronicles” was first done, it was both a commercial and a critical success, but some feminists felt that the play, which concludes with Heidi sitting in a rocking chair, singing to the baby she has adopted, was a betrayal of all they had fought for.

If the drama hasn’t held up well, it has less to do with compromised politics than inexperienced writing. Wasserstein too often settles for punch lines when something deeper is called for.

But Moss makes us care about Heidi’s struggle to create a life that she can live with both politically and personally. Reliant on community yet unable to conform to the latest communal trend, her Heidi must find her own solutions. It is this solitary journey, traversed by Moss more resonantly in her silences than in her monologues, that keeps “The Heidi Chronicles” from seeming completely dated.

On screen, Mulligan’s great strength and occasional weakness is her emotional accessibility. She doesn’t so much act a role as feel it. When she speaks, she taps into the internal pressures underlying her character’s words. When vulnerability is called for, as in “An Education” (the film that put her on the map), she shines. But sometimes it can seem, as in “Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps,” that she is always either crying or fighting back tears.

Daldry reins her in beautifully in “Skylight.” Mulligan’s performance has an austerity that befits her character, who has been trying to expiate her guilt over the long, adulterous affair that she had with Tom while his wife was dying. Tom’s wife has been dead for a year now, but Kyra, who fled the relationship after it had been exposed, only finds out when Edward (Matthew Beard), Tom’s son, drops by unexpectedly, worried about his dad’s disintegrating psychological state.

When Tom barges into her apartment, he is taken aback by the penury of her living situation. Before even taking off his coat, he offers to have central heating installed. She’s cooking spaghetti, but he tries to tempt her into a “proper dinner,” playing Mephistopheles to her ascetic Faust.

The play, which had its Broadway premiere in 1996 with Michael Gambon and Lia Williams, is a pas de deux between characters who share a complicated romantic history yet who are worlds apart ideologically. Mulligan’s Kyra, raised comfortably middle class but more at home in a low-income milieu, is living out her creed. She doesn’t proselytize or grandstand because her actions speak for themselves. She teaches because making a difference in one underprivileged life is reward enough.

Nighy’s Tom, who grew up poor, doesn’t believe in charity or altruism — self-sufficiency is his religion. He preaches to counter the liberal rhetoric that his uphill experience has taught him is a lie. He can afford to be generous to Kyra because he wants her back. She, however, isn’t up for sale.

Nighy, acting as though an electric current were running through his wiry body, portrays a man who isn’t accustomed to being thwarted. His is the showier role, and he has a field day. But his virtuoso turn depends on the stillness of Mulligan’s Kyra. Her embodied conviction is what Nighy’s Tom flails against. Mulligan allows you to imagine the emotions left unsaid. She finds complexity in holding back, a credit both to Hare’s richer-than-usual psychology and her growing maturity as an actress.

As in “The Heidi Chronicles,” the wayward human dimension of “Skylight” keeps the politics from becoming schematic. That’s a boon to actors of Moss and Mulligan’s caliber, who have an allergy to dogma, understanding that politics is complicated for all the same reasons individuals are.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.