Review: Tyson’s inviting ‘Trip to Bountiful’ at the Ahmanson Theatre

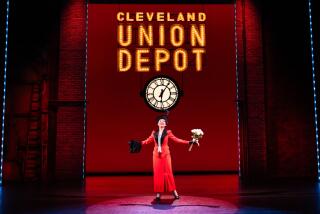

Michael Wilson’s revival of Horton Foote’s “The Trip to Bountiful,” which has just opened at the Ahmanson Theatre, premiered on Broadway in 2013 to a bounty of praise and nominations, especially for Cicely Tyson, who won the Tony Award for her portrayal of Mrs. Carrie Watts.

Originally written as a teleplay in 1953, “Trip” tells the story of an elderly woman’s return to her hometown of Bountiful, Texas. A trustworthy vehicle for star turns—by Lillian Gish and Geraldine Page, among others—it has been recast in this production with black characters.

The transformation, conceived by the playwright’s daughter, Hallie Foote, not only tempted Tyson back to the stage after a 30-year hiatus but also imparts new resonance to the deceptively sentimental story.

Any fear that Tyson might not live up to the hype dissolves within moments of her appearance—once, that is, the excited audience has adjusted to the modest scale of the scene.

Looking tiny and brittle in a fuzzy robe, Carrie sits in a rocking chair, watching the middle-of-the-night traffic outside the Houston apartment she shares with her son, Ludie (Blair Underwood), and daughter-in-law, Jessie Mae (Vanessa Williams). Her Texas-accented chatter to Ludie, a fellow insomniac, is a little faint. It doesn’t, right off the bat, scream Tony Award.

Just wait. The ageless Tyson (literally: whether she is 80 or 89 remains an open question) has such a powerful expressive gift that as the action develops, her briefest utterance—from a snippet of a hymn to a dry “Mm-hmm”—accomplishes a novel’s worth of exposition.

The very shape of her body transforms with Carrie’s moods. When upset, she clatters around in a stooped, hobbled hurry. When exhilarated she flutters and sways as if about to take flight.

But in the first scene she’s slumped in despair. The Watts family lives in a two-room apartment (designed by Jeff Cowie as a cutout within a bank of windows, in which lights flick on disapprovingly at any noise). Ludie doesn’t earn a lot, so the callow Jessie Mae depends on her mother-in-law’s monthly pension check to fund her visits to the beauty parlor and the drugstore for Coca-Colas.

In exchange for these wan luxuries she must keep a sharp eye on the old lady, who despite her meek promises and “sinking spells” is always scheming to escape to Bountiful, her Eden, which she hasn’t seen in 20 years.

As Jessie Mae, Mother Watts’ frivolous, narcissistic, over-caffeinated jailer, Williams makes a wonderfully entertaining foil. The nearest thing the play offers—besides life itself—to a villain, she is written with sympathy, and Williams’ portrayal is so sharp and assured that at one point, when she is offstage, the audience bursts into fond laughter at the honk of an car horn attributed to her.

Underwood is also extraordinary as the reserved Ludie, caught in the crossfire between his mother and wife. In Underwood’s moving interpretation, this deeply decent man is so overwhelmed by his responsibility for the two women’s happiness that their modest longings wound him like accusations.

This dynamic may sound dismal, but Wilson plays up the considerable comedy as Carrie’s escape plan is repeatedly foiled by the self-absorbed Jessie Mae. Their battle even evokes cartoons—say, “Tom and Jerry”—in which a small, resourceful character outwits a menacing but duller-witted foe. The association of Carrie with a wayward, enterprising child ensures the audience’s thorough investment in her scheme.

On the bus (a cozily-lighted moving set piece, swept by passing headlights, against a starry black sky), Carrie befriends a lovely young woman, Thelma (Jurnee Smollett-Bell), with whom she exchanges confidences.

Arriving in Harrison—Bountiful has no bus stop—to a series of crushing revelations, she goes on to lead Thelma in a hymn, as the ticket attendant (Arthur French) looks on with a fond smile and even the audience joins in. Such pluck in the face of adversity verges on kitsch; for a moment a wave of syrupy sentimentality seems to be building up in the wings.

But the dialogue Foote crafted for Carrie conceals both its skill and a quiet despair. A master of exposition, he drops in tragic revelations where they’re least expected, as when Carrie offhandedly mentions old wounds to Thelma—a tragic romance, a dead child—that deepen our understanding of her as a tragic figure. For all their sweetness and candy-colored dresses, the women exchange a poignant parting look that’s unmistakably an acknowledgment of mortality.

It’s hard to believe that the play has not always been about race, so delicately and persuasively has the topic become its subtext here. Cowie’s rendering of the Houston bus station has a “Colored Only” sign on the ticket counter; the white sheriff (Devon Abner) who discovers Carrie asleep in the bus depot is briefly terrifying (although the play never really puts her at risk; her tragedies are all in the past).

And when Mother Watts reaches Bountiful at last, the landscape is indeed breathtaking, but the decrepit house speaks eloquently of past hardships; Ludie’s refusal to share in his mother’s nostalgia makes sense.

Ultimately, what makes this harrowing “Trip” endurable, even uplifting, is Carrie’s hard-won humor and wisdom, and the peace she is able to make with her own unhappiness before she is caught and marched back to Houston.

“There are worse things,” she dryly retorts when the sheriff reflects on her childhood friend’s “lonely death alone in a big house.” This small, tart moment will stay with me—as will my gratitude for this unforgettable production.

“The Trip to Bountiful.” Ahmanson Theatre, 135 N. Grand Ave., Los Angeles. 8 p.m. Tuesdays through Fridays, 2 and 8 p.m. Saturdays, 1 p.m. Sundays. Ends Nov. 2. $25-$115. (213) 972-4400 or www.CenterTheatreGroup.org. Running time: 2 hours, 10 minutes.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.