Omar Sharif, a shapeshifter on screen, was a trailblazer and a flashpoint

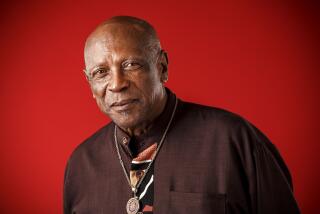

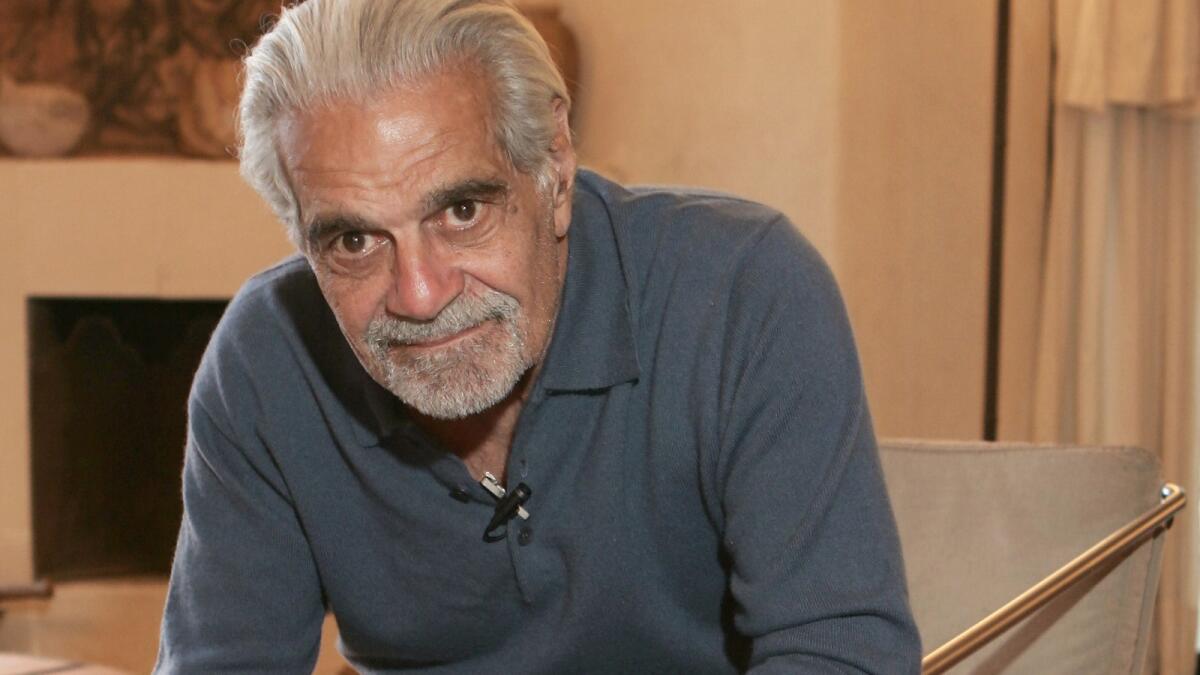

Egyptian actor Omar Sharif at his home in Cairo on April 4, 2007.

Throughout his long career, the Egyptian star Omar Sharif, who died Friday at the age of 83, was known for both the subtlety and grandeur of his roles. He won acclaim for many of them — multiple Golden Globes, a Cesar award and an Oscar nomination.

And, of course, there’s his signature scene: the one in which he moves across the desert on a camel in “Lawrence of Arabia,” now etched into out cinematic consciousness.

But one of Sharif’s largest legacies is sociological. The man born Michel Chalhoub was not only one of the first Arab actors to cross over to mainstream popularity — he was one of the first actors to play a wide variety of ethnic characters, period.

Sharif’s early work was playing people of Arabic ancestry, such as, in his native Egypt, the part of Ahmed in the 1954 Arabic-language “Struggle In the Valley,” in which he stars as an engineer caught in a revenge plot. Eight years later he would make his mark on Western cinema in “Lawrence of Arabia” as Sherif Ali, the paragon of Arab nationalism.

But those early roles quickly morphed into parts that went far beyond the Arab world — in “Doctor Zhivago,” where he played the Russian Yuri Andreyevich Zhivago; as Jewish gangster Nicky Arnstein in “Funny Girl;” in 2003’s French-language “Monsieur Ibrahim,” in which he plays a Turkish immigrant who takes in a Jewish orphan; or as Latino revolutionary Che Guevara in 1969’s “Che!”

At a moment when onscreen diversity remains a pressing topic, Sharif was both a trailblazer and, in some cases, a flashpoint. After all, some of his parts were also controversial. The decision to cast him as Arnstein was criticized by some, and his role as Guevara landed uncomfortably for others. The issues surround race and casting, for all their modern, social media-enhanced qualities are manifold and complex, and when a director is lambasted for casting an actor in a role outside his own race — as “Aloha” director Cameron Crowe recently was for having Emma Stone play a woman of Asian origin — it has roots in the Sharif debate.

Still, there was a key difference between many of these instances and Sharif, the latter of whom, of course, was a minority playing other minorities. The actor who perhaps most carries on this shapeshifting mantle today is Oscar Isaac, who was born in Guatemala but has played a Russian American bodyguard, a British monarch, a Polish American politician and an American mongrel, in addition to a Latino immigrant.

Part of Sharif’s ability to tackle so many different roles is that he possessed a look more exotic than many British or American-born actors, and a cynic might say that these opportunities really had as much to do with Hollywood’s inability to distinguish between ethnicities, or at least to cultivate actors from other places, than anything else. But it was Sharif’s own talent — and maybe just as important, his ability to intuit otherness, even if it wasn’t his otherness — that enabled him to play these parts.

A younger generation may not be as familiar with Sharif, who hasn’t starred in a major English-language film in more than a decade. But the easy fluidity he brought to the screen paved the road not just for him, but for many other actors to take on roles that have historically not been as open to them. Any time we watch Sofia Vergara as a prime-time mother or Michael B. Jordan as a triumphant superhero or even Justin Lin get behind the camera to make one of the biggest movies in Hollywood, we’re seeing not just a more representative slice of the global population but a little bit of what Sharif first made possible.

Twitter: @ZeitchikLAT

MORE ON OMAR SHARIF:

Celebs remember the Egyptian actor as ‘dashing,’ ‘gracious,’ ‘loyal’ and ‘wise’

In Egypt, Omar Sharif’s death met with sadness -- and a young man’s shrug

More to Read

Only good movies

Get the Indie Focus newsletter, Mark Olsen's weekly guide to the world of cinema.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.