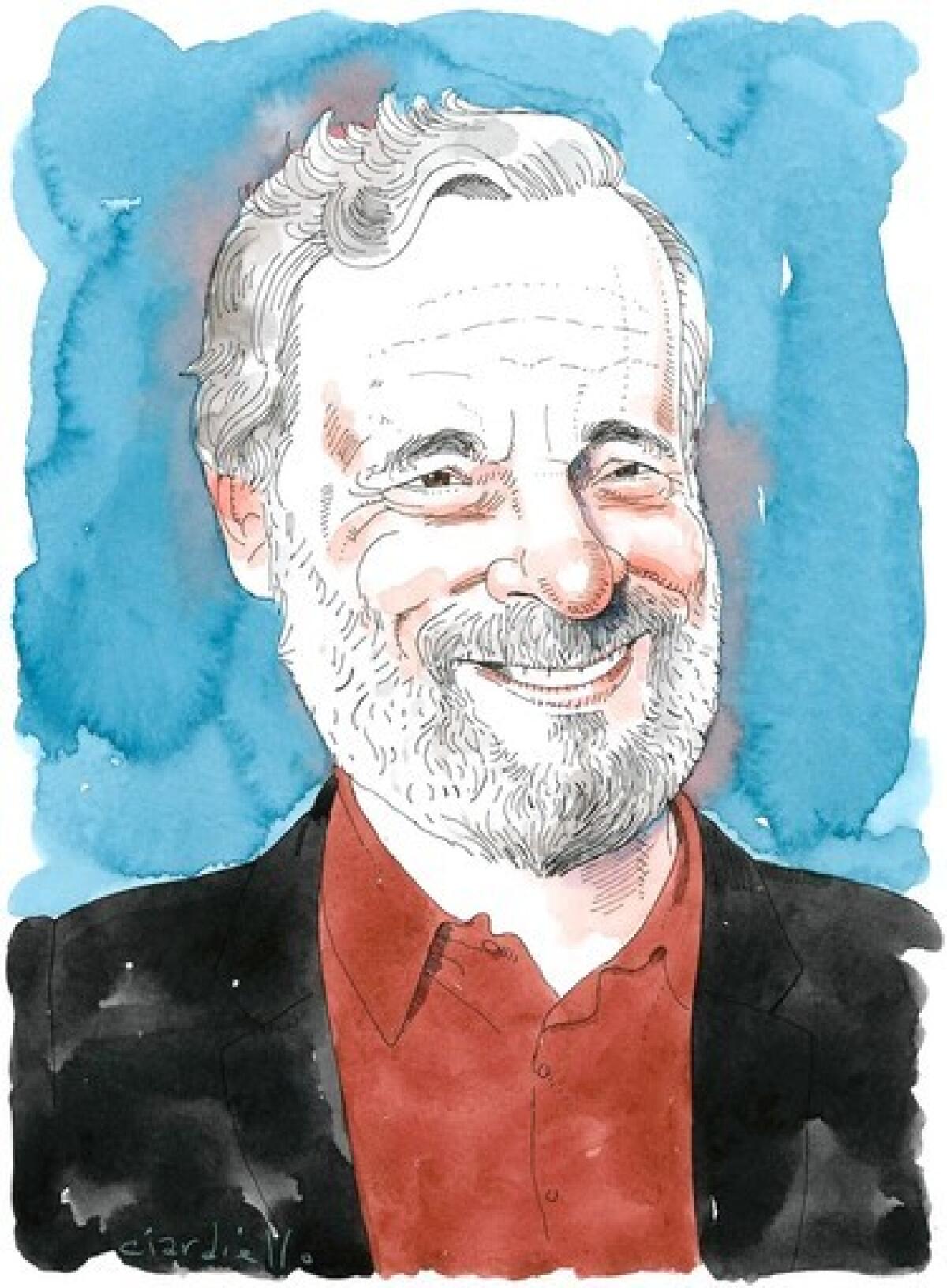

Stephen Sondheim: Merrily he rolls along

Stately and rumpled, Stephen Sondheim descended from an upper floor of his elegant East Side townhouse and submitted to the interview as though it were a necessary barber shop shave. He’s used to these intrusions — the artist obliged to natter on about his work was one of the themes of “Sunday in the Park With George” — but this year the distractions have gone to a harrying new extreme.

Sondheim turned 80 in March, and he’s been blowing out the candles ever since. There was an all-star birthday concert at Lincoln Center (scheduled to air on PBS on Nov. 24). Broadway paid homage with a musical revue, “Sondheim on Sondheim,” interspersed with video clips of the maestro musing about art and life. And now that he has a new book out, “Finishing the Hat,” he finds himself once again thrust into the spotlight, with a West Coast tour that includes a UCLA Live conversation at Royce Hall on Monday night with KCRW-FM’s “Bookworm” host Michael Silverblatt.

Hey, when’s a guy going to get a spare minute to compose the next “Sweeney Todd”?

Ever alert to paradox, Sondheim described all this public attention as “thrilling and embarrassing.” “There’s an up- and downside to being venerated,” he said. “You start to believe your own notices, and that’s very dangerous. At the same time, it does feel like it’s gold-watch time. It’s ‘thanks so much for coming to the party.’ They’re nails in the coffin, is what they are.”

The far-off look in his eyes, as though tracking a giant hourglass emptying somewhere in the middle distance, is reminiscent of Trigorin, the writer in Chekhov’s “The Seagull,” who strives to deromanticize the artist’s life to a young gaga actress: “Here am I talking to you and getting quite excited yet can’t forget for a second that I’ve an unfinished novel waiting for me.” Or as Sondheim apologetically put it, “Even as I’m sitting here talking to you, and I’m having a perfectly fine time, part of my head is saying, ‘I should be up at the computer.’ My Jewish guilt is building up.”

His life has been consumed of late by “Finishing the Hat,” an extraordinary book of commentary on his own work from “Saturday Night” through “Merrily We Roll Along.” Scattered throughout are short, spiky essays on an elite group of lyricists, all dead and safely ensconced in the pantheon. Sondheim has been hard at work on the second volume, which will pick up with “Sunday in the Park With George,” the show that contains the autobiographical song about compulsive creativity that has provided his title. The subtitle, “Collected Lyrics (1954-1981) With Attendant Comments, Principles, Heresies, Grudges, Whines and Anecdotes,” has the delightful accuracy one expects from the man roundly hailed as the American theater’s greatest living songwriter.

Although Sondheim claimed that “prose is not a natural language” to him, his verbal gifts of precision and concision are on magnificent display. He offers authoritative verdicts on such legends as Ira Gershwin (“He is often undone by his passion for rhyming, for which he sacrifices both ease and syntax”), Noel Coward (“Most of Coward’s lyrics come in two flavors: brittle and sentimental”) and Lorenz Hart (“the laziest of the preeminent lyricists, and one of the most disconcerting…”).

The book escorts us into the workshop of Sondheim’s mind, inviting us to evaluate songs through his own exacting eyes. For example, in parsing his mentor and father-figure Oscar Hammerstein II, Sondheim takes issue with redundancies (“I could say life is just a bowl of Jell-O / And appear more intelligent and smart”) and strained imagery (“When the sky is a bright canary yellow” — a color that makes him want to take refuge in a “storm cellar”). But these quibbles are contextualized in an eye-opening comparison between Hammerstein and Eugene O’Neill that suggests these writers’ soaring “theatrical imaginations” are compensation for language that “is usually more earthbound than earthy and tends to veer off into preachment.”

This intensive critical scrutiny might indicate a serious case of “anxiety of influence,” one titan toppling his forebears in an Oedipal wrestling match for pride of place in posterity. But as Sondheim reminded, “I cover 12 of them, and half of them I really like, almost without reservation.” What’s more, he unleashed his pointy editor’s pencil on himself, complaining that some of the lines of “America” in “West Side Story” “melt in the mouth as gracelessly as peanut butter and are impossible to comprehend….”

A British playwright friend objected to the way he didn’t consider the class system that informed Coward’s sneering satire of the rich, an attitude Sondheim unfavorably contrasts with Cole Porter’s (“Both make sport of the haute monde, but Porter does it with fondness, Coward with disdain”). Yet it’s hard to miss the spirit of generosity underlying this hardcover master class — essentially, a passing of trade secrets to the next generation.

“Teaching is a big deal to me,” Sondheim said. “I was asked to do a book of collected lyrics, and I said I would do it only if I could write about the craft of writing lyrics. To my horror they said, ‘All right, go ahead.’”

“I just think it’s interesting to read how somebody does something, whether it’s raising cattle or making pewter ashtrays. All they have to do is be articulate and honest about it. I figure I have no problem with being honest about my own flaws or what I think are the flaws or virtues of others. It doesn’t bother me, because I’m very confident about what I do and I have opinions. And opinionation is very important in the arts.”

When asked whether there’s been a drop in skill level with the current generation of lyricists, he refused on principle to speak about “living writers,” having been burned often enough in the press to know how it feels. But he admitted that the business of Broadway has made it challenging for today’s innovators to get produced there.

“Most of the so-called serious musicals, like ‘Rent,’ ‘Next to Normal’ and ‘Spring Awakening,’ started in off-Broadway houses,” he said. “Nobody would ever put those shows right away on Broadway. Things are just too expensive. Producers want familiar songs, big names or a tested product. So I think if you’re a young writer, the only chance you have is starting either in regional theater or off-Broadway.”

Sondheim says he was “completely gobsmacked” to have had a Broadway theater named after him. But does he see a metaphor for the current state of theatrical affairs in that the inaugural production in this rechristened venue is “The Pee-wee Herman Show”? “I made jokes about it too,” he admitted. “But it isn’t just Pee-wee Herman. This is also reflective of the jukebox musical. In other words, a popular character in this case, as opposed to a popular score, is presented to an audience that knows what it’s going to get before going into the theater.”

Does he worry that our willingness to inhabit new fictional worlds has been compromised by the technological mania of contemporary life? He nodded wearily and admitted that he doesn’t use an iPod for fear “of walking right into the path of a Fifth Avenue bus.” Nor does he allow himself to hang out in Internet chat rooms, understanding that someone of his “addictive nature” might end up there all the time.

If this makes him sound like a throwback, so be it. “I’m a cliché,” this inveterate cliché-crusher said at one point. “I’m a person getting old.” Sitting on the couch, he gives the impression of a timeless monument — scruffy, relaxed and settled into his final shape.

Often credited with teaching the musical the meaning of ambivalence, Sondheim rejected this as patently false. (“Gosh, you know, shows like ‘Show Boat’ and ‘Porgy and Bess,’ they tell stories of some complexity in terms of interrelationship of characters.”). Yet he says his sensibility, sometimes derided as “cold” (another bogus charge, in his view) has been largely influenced by drama: “Even today, I don’t go to very many musicals. I go to plays, because that is what I, as an audience member, want to go see.”

As for the future, he has his sights set on a major new production of a tricky older work, “Merrily We Roll Along,” a show he accepts may never be popular. “To start with the sour part of the character and then go back until you get the sweetness — I love that as a structure, but audiences may not be able to do that,” he said. But London (and likely New York) will be getting another crack at it in the not too distant future.

He sounded a touch melancholy that “Road Show,” which received mixed reviews off-Broadway in 2008, didn’t catch fire with the critics (or Broadway producers). Like Dot in “Sunday,” he knows when to “move on,” but is the hunger for original work still there?

“The trouble with getting old is you get less hungry. So no, I’m not as hungry as I wish I were, but I am hungry. I mean I’m restless. As long as I’m busy, and I am busy finishing the second volume of the book. But then I’m going to start feeling itchy. I have been nibbling around at new projects, but I haven’t committed myself to anything yet. I can only concentrate on one thing at a time. I don’t have a compartmentalized mind.”

Theatergoers have reason to be grateful for that unwavering focus.

More to Read

The biggest entertainment stories

Get our big stories about Hollywood, film, television, music, arts, culture and more right in your inbox as soon as they publish.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the Los Angeles Times.